A bizarre mix of Supermarionation and live-action which was cancelled after 13 episodes because Lew Grade didn’t like Stanley Unwin’s gobbledygook. That’s the history of Gerry & Sylvia Anderson’s The Secret Service as most sources dish it out. It’s usually framed as a weird footnote in the Anderson story in between the steady waters of Joe 90 and the big comeback with UFO. Some critics accuse the Andersons of being either uninspired or unhinged when they devised the series’ format and that it was doomed to fail from the start because the adventures of a super-spy-priest and his shrinking gardener couldn’t possibly make good TV.

Those critics will say that Gerry and Sylvia had lost their touch and didn’t care about Supermarionation now that they were away from the day-to-day operation of the studios on the Slough Trading Estate and working on their live-action feature film, Doppelgänger, at Pinewood. Some might even suggest that The Secret Service was a case of self-sabotage just so Century 21 could be released from its puppetry shackles by Emperor Lew to make live-action shows.

But let’s be sensible. It makes for a dramatic and quirky story to say that all the people in charge just dropped the ball spectacularly when they made The Secret Service, having scored an amazing home run with Thunderbirds a few years earlier. But television in 1969 was not the same baseball field that it had been in 1965. The goal posts had shifted, and I think some serious post-match analysis is required to really determine whether The Secret Service was Century 21 and ATV bowling an over, potting a cue ball, or forfeiting the match… and just like this sporting metaphor, it’s going to get messy. How about a thorough review of the entire series episode by episode, shot by shot? Yes, I thought so.

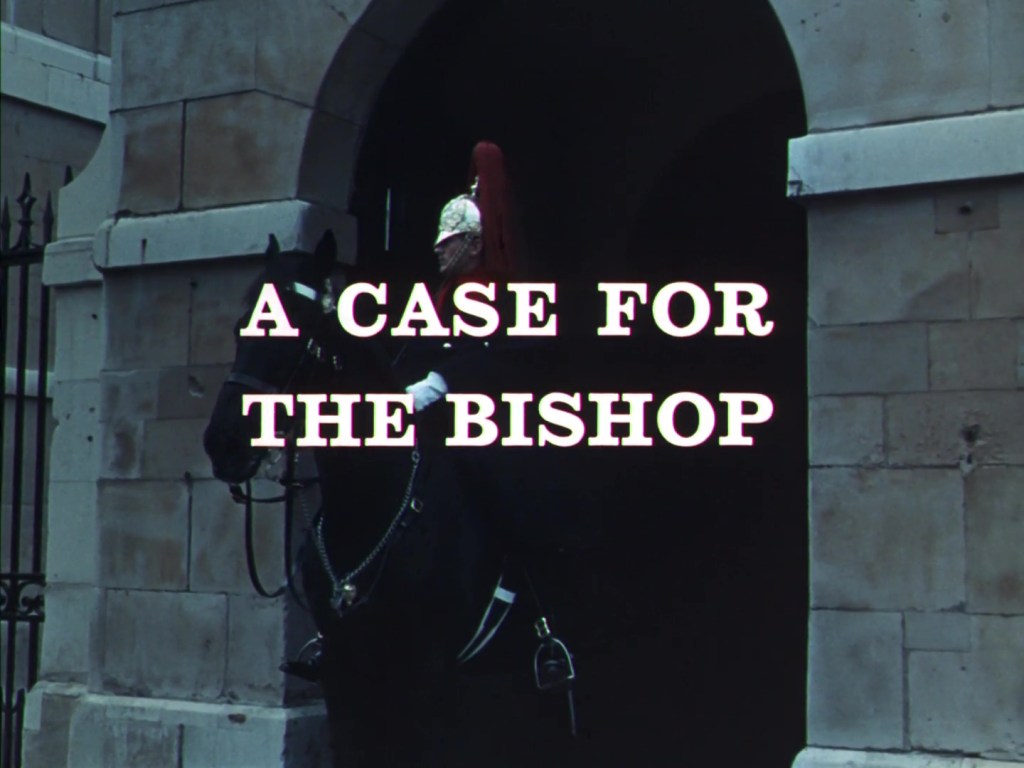

Original UK TX:

Sunday, September 21st 1969

5.30pm (ATV Midlands)

Directed by

Alan Perry

Teleplay by

Gerry & Sylvia Anderson

It’s a reflection of the post-Thunderbirds success that the whole studio, to fall in line with other subsidiary companies, was re-branded towards the image of futuristic filmmaking, with Gerry Anderson’s name placed firmly at the top of it regardless of his day-to-day involvement. Brand-image was now something that had a part to play in the Supermarionation story. Prior to Thunderbirds, the studios were building their reputation and figuring out who they were – by the time The Secret Service came along, that reputation was emblazened across the company and packaged up neatly in this exciting animated ident, and with Barry Gray’s dramatic violin sting. Is it a bold statement of success and self-confidence, or a suggestion that they had conquered Everest and had no-where else to go?

It’s worth noting that these reviews will make use of the best available material for the illustrative screenshots. The release of This is Supermarionation and HD21 from Network in 2014 provided high-defintion blu-ray releases of the first and last episodes of The Secret Service – A Case For The Bishop and More Haste, Less Speed. The remaining episodes only made it as far as DVD in standard definition back in 2005, again from Network. As Network Distributing ceased trading in 2023, and a full-blown blu-ray release of The Secret Service was always deemed pretty unlikely anyway, I decided that mixing between DVD and the two blu-ray episodes would be our best shot at getting a good look at the show.

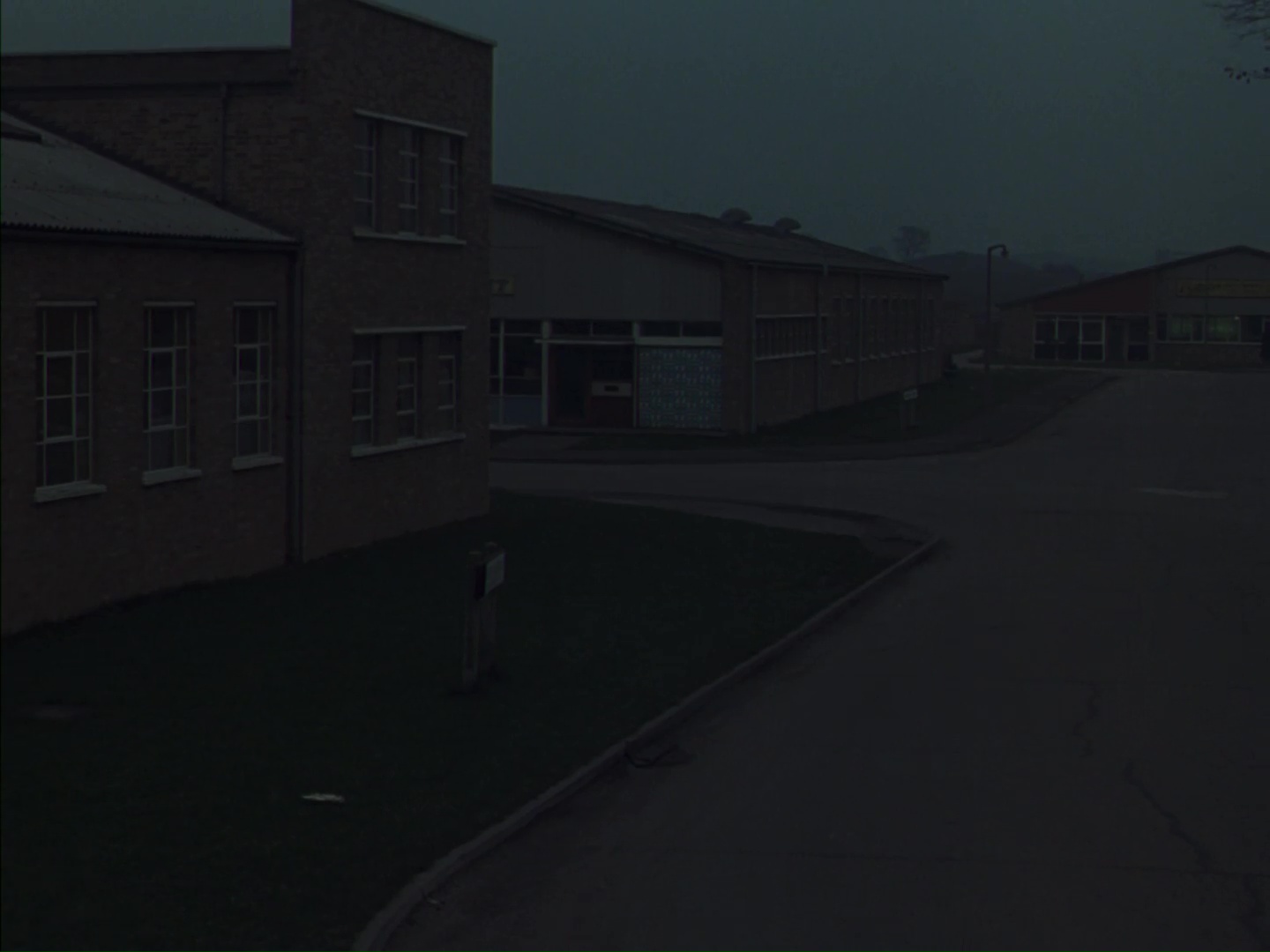

That being said, the HD scans of A Case For The Bishop and More Haste, Less Speed were not particularly polished to the usual high standards we would come to expect from Network’s later Anderson blu-ray releases, and therefore appear much darker than the cleaned-up DVD versions of the episodes. So you’ll notice that while the HD screengrabs used in this review of A Case For The Bishop contain more detail than you’ll see in subsequent reviews, the colouring is, in my opinion, inferior to the SD screengrabs you’ll see in future articles. Basically, I’m damned if I do and damned if I don’t. I even attempted to colour-correct the two blu-ray episodes myself but… well… there’s a reason why Network were the best in the business for these restorations and I just sit behind a computer screen bashing a keyboard with my fists until words come out. R.I.P. Network.

Sorry to contribute to the morbid tone, but here are some of the Century 21 buildings on the Slough Trading Estate which don’t exist anymore following their demolition in 2017. Specifically, the unit shown was leased from 1966 onwards and primarily housed the puppet stages and art department. To our right, connected by a walkway across the car park, is the original building occupied since 1963 for shooting puppets and special effects for Stingray. Out of shot on the left, we would see a third Century 21 building which was also leased from 1966 as a result of the doubled up production between the second series of Thunderbirds and the Thunderbirds Are Go feature film. This high angle shot was either taken from a crane, or a particularly tall roof or gantry attached to a building adjacent to the enormous cooling towers which dominate the trading estate on Edinburgh Avenue. So far, I think you’ll agree that these insights are interesting but rather dry. To re-dress the balance – farts.

More glamorous shots of the Slough Trading Estate at night with such exotic locales as the junction between Oxford Avenue and Banbury Avenue. It’s worth noting that this entire opening scene was a late addition to the script for A Case For The Bishop. Gerry & Sylvia Anderson’s original teleplay, as published in the PDF archive on the DVD release, details that the episode was intended to open with something of a “flash forward” to the episode’s climactic car chase sequence which would then neatly tie into the standard opening titles for the series. The car chase would then play out again, in context, later in the episode. The idea would have been a neat evolution of the “this episode” teaser of Thunderbirds and set up an intriguing and suitably quirky mystery. “How did a priest in a Model T Ford end up in an armed car chase?!” the audience would have cried, and then stayed glued to their television set for the remaineder of the show to find out… OR one could make the dreadfully cynical accusation that such a lengthy reveal of the episode’s climax would have dispelled all the tension, given away too much, and bewildered viewers with its quirky structure.

Whichever way you look at it, the decision was ultimately made to switch over to a more conventional pre-titles scene – a structure which had been experimented with in some Joe 90 episodes to great success and would become a staple of modern television in the present day.

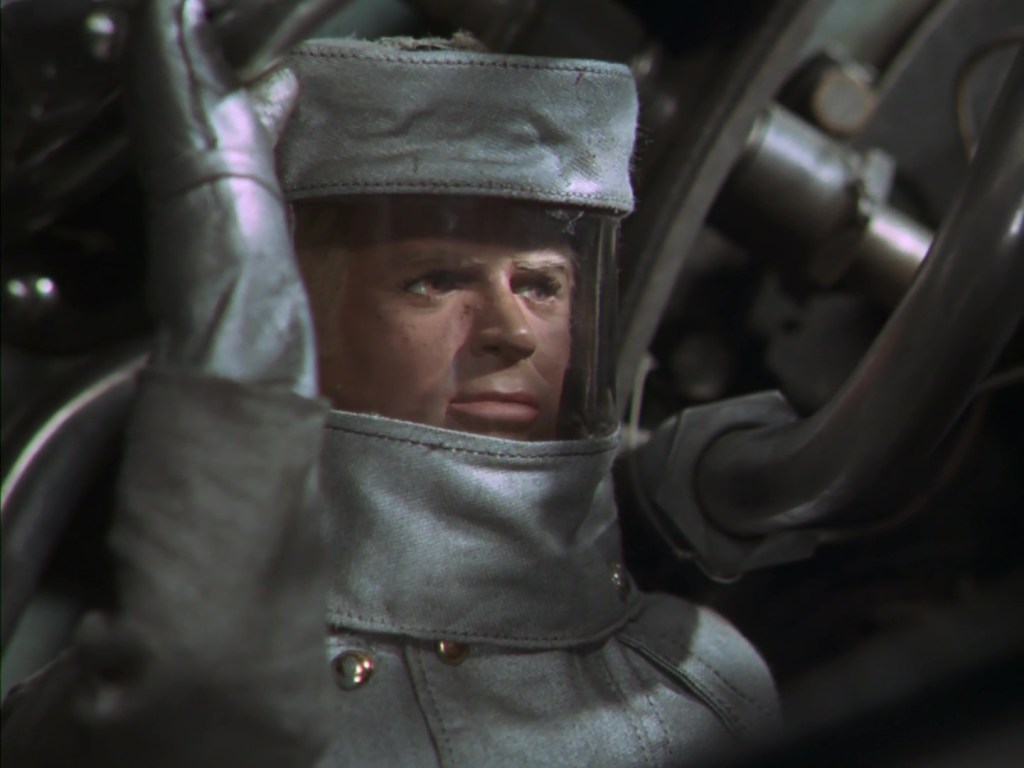

Back over in the Century 21 building, we get our first glimpse at a human person. Yes, one of those live actors we’ve heard so much about! Isn’t he swell? The identity of the performer is unknown, as is the case for all of the live-action stand-ins for the series with the exception of Stanley Unwin. Our security guard starts by literally looking straight at the camera crew through the window, waiting for his cue, and then does a bit of standing up and shuffling around. Amazing. Who needs puppets with performances like that, ey?

In fact, it’ll be quite a while yet before any puppets make an appearance on-screen, which isn’t exactly what one might expect from “A Gerry Anderson Century 21 Television Production” which has supposedly been “Filmed In Supermarionation”. I’d go as far as to say that long-winded night-time shots of an empty trading estate occupied by one human man is about as off-brand as you can get for an Anderson production. It also doesn’t help that we diehard fans immediately go “that’s the Slough Trading Estate” as soon as the show starts – it doesn’t make the best impression that the series’ prominent location filming is going to wow us if the first shots involve the camera crew barely stepping out of the studio’s front door. Incidentally, the room we see lit up here was likely the studio’s conference room found in between Derek Meddings’ office and the accounting office… just in case you were looking for more location-spotting thrills.

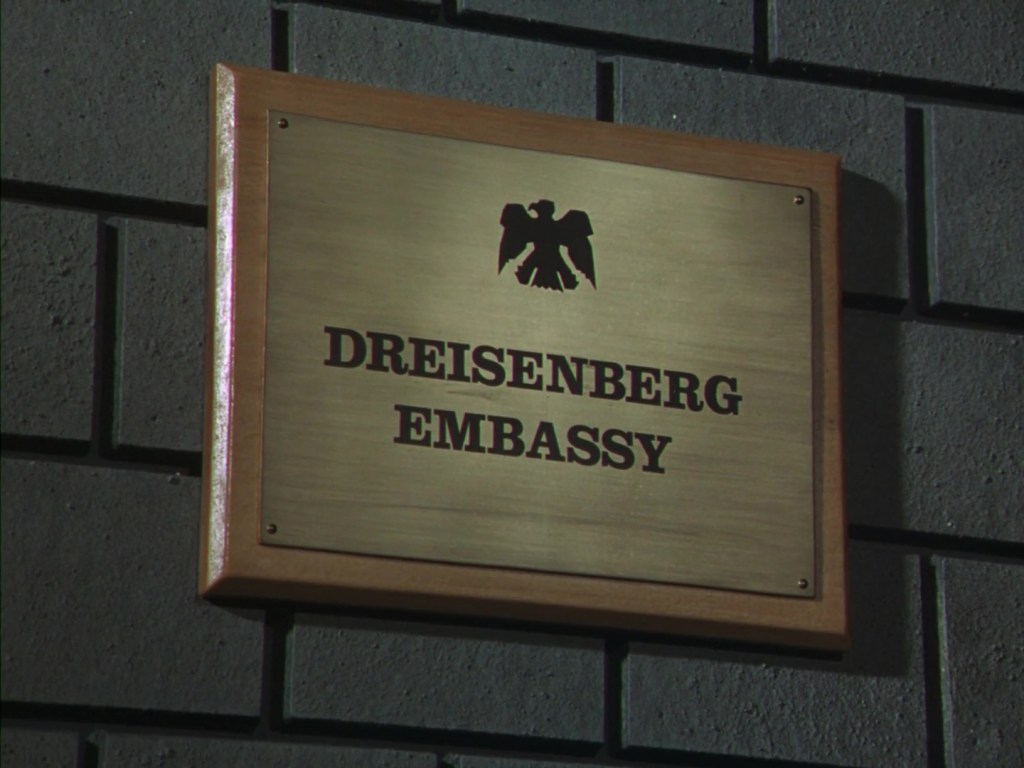

Since we aren’t allowed to see any puppets just yet, the camera operator pans across to this sign while we hear the sound of glass breaking and a gentleman getting shot. If you’re unfamiliar with The Secret Service and how it uses live-action, puppetry, and models, the rule of thumb is that the marrionettes and miniatures are used for close-ups while the live-actors and real vehicles are used for distance shots involving people walking or cars driving down ordinary roads. We’ll judge the results on a case-by-case basis as we make our way through the series, but as in this sequence I can’t help feeling like something’s missing. It’s difficult to connect with a scene when the way it’s shot forces us to be as far away as possible from the actors – or in this case not even looking at them.

Whip-pan transition! Nice to see some of the old hallmarks.

Tea and cigarette ash soil important-looking paperwork. I assume the Century 21 conference room was usually kept at least 3% tidier than this.

Our hapless hero is out for the count and doesn’t manage to finish his telephone call for help. It’s actually quite a grim sight, due in part to the use of a human instead of a puppet. The moody lighting (not helped by the darkness of the HD transfer), the slow-moving camerawork, and the face kept out of view and at a distance all feels incredibly alien and unnerving. Even in the most grave moments of Captain Scarlet, no scene ever felt quite this remote and cold.

Sylvia Anderson’s voice is heard on the other end of the phone – probably a genuine call to check if the conference room is free yet.

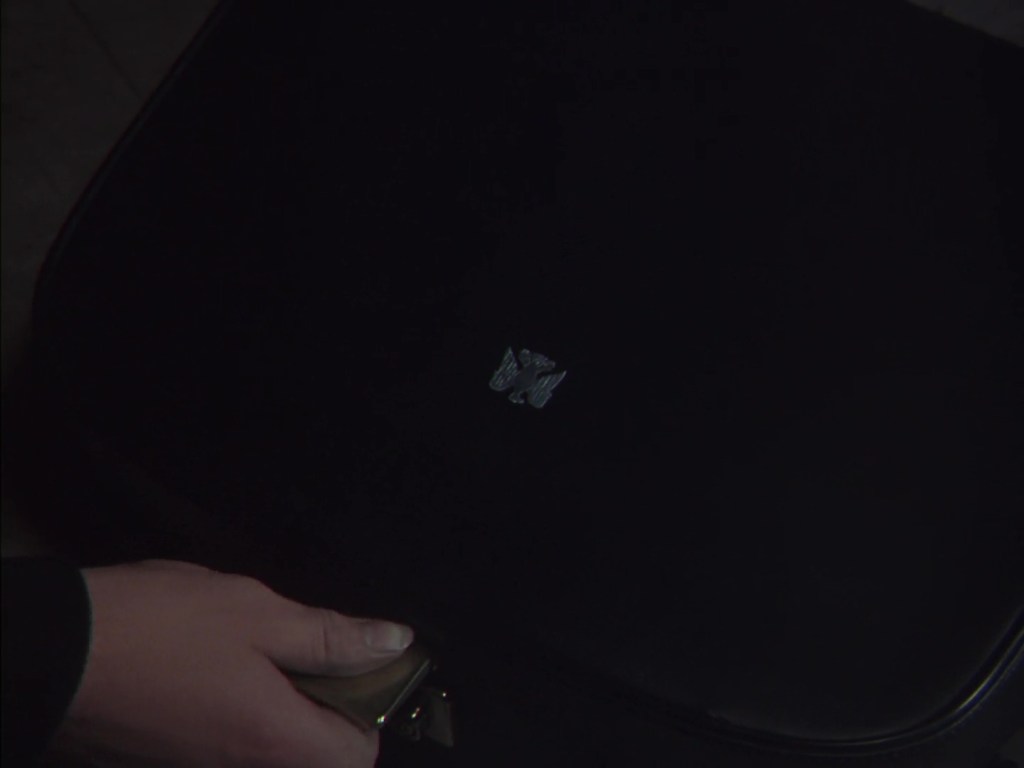

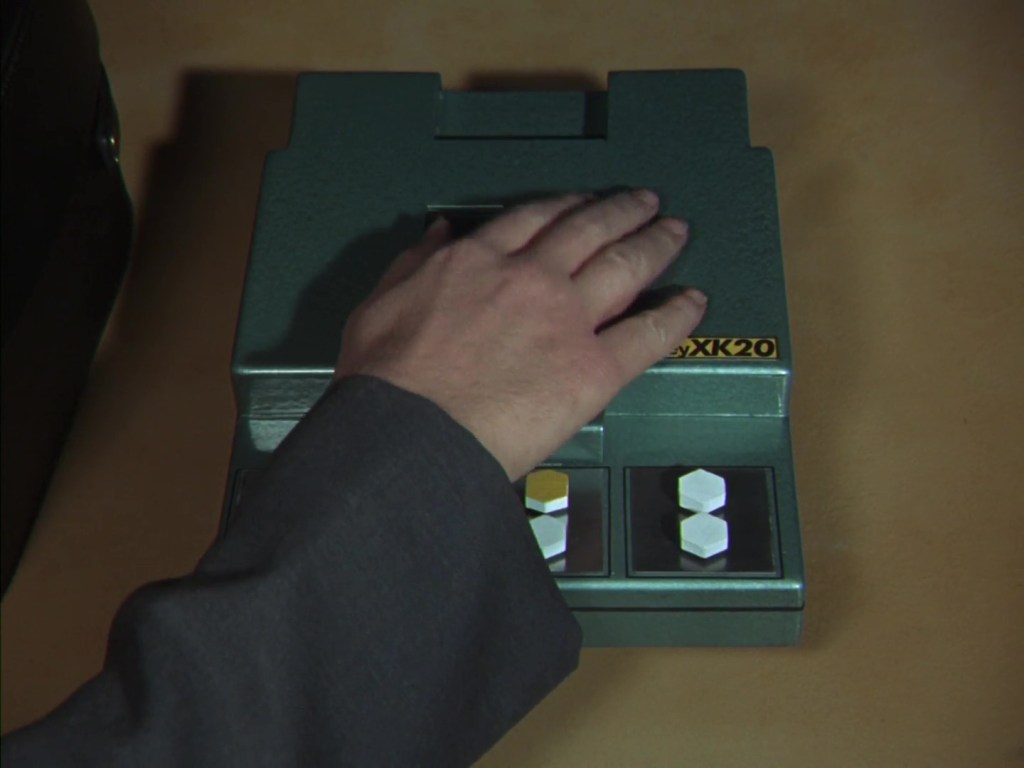

A semi-futuristic door gets blown open by a pair of human hands – a much more familiar sight in the world of Supermarionation since live-action hand inserts were a thing ever since Four Feather Falls. A shiny box labeled “Healey XK20” is popped in an ominous black suitcase bearing an eagle emblem. The location filming of The Secret Service necessitated the setting of the series in the present day, somewhere between 1968 (when shooting started) and 1969 (when the series aired). That’s obviously quite a departure from previous Supermarionation series which had usually been set one hundred years hence. But just how strictly did Century 21, a studio literally named after its futuristic output, stick to this contemprorary setting? Well, the XK20 is apparently a minicomputer, and a quick bit of research reveals that the prop is around half the size of the 1968 Nova Minicomputer designed by engineers at Data General. So let’s just say the prop-maker was almost accurate in their size estimations. In fairness to them, the Andersons’ script called for the minicomputer to fit inconspicuously in a suitcase so therefore had to be made smaller than the contemporary minicomputer designs of 1968.

Incidentally, the first Nova Minicomputer had 32KB of memory and sold for $8,000 – which comes to about $70,000 today when adjusted for inflation. Bargain.

Bong! Time for the opening titles. Keep in mind that the original script would have seen us move straight from Gabriel arriving home at the vicarage after the car chase scene to…

… this shot of the window for the titles to begin. I think it would’ve been a neat transition. The location used for the vicarage throughout the series was Foxlea Manor on Dorney Wood Road, Buckinghamshire. Today, the house is difficult to spot from the road behind the property’s tall gates, but even a passing glimpse indicates that this original part of the building has changed little between 1968 and 2023.

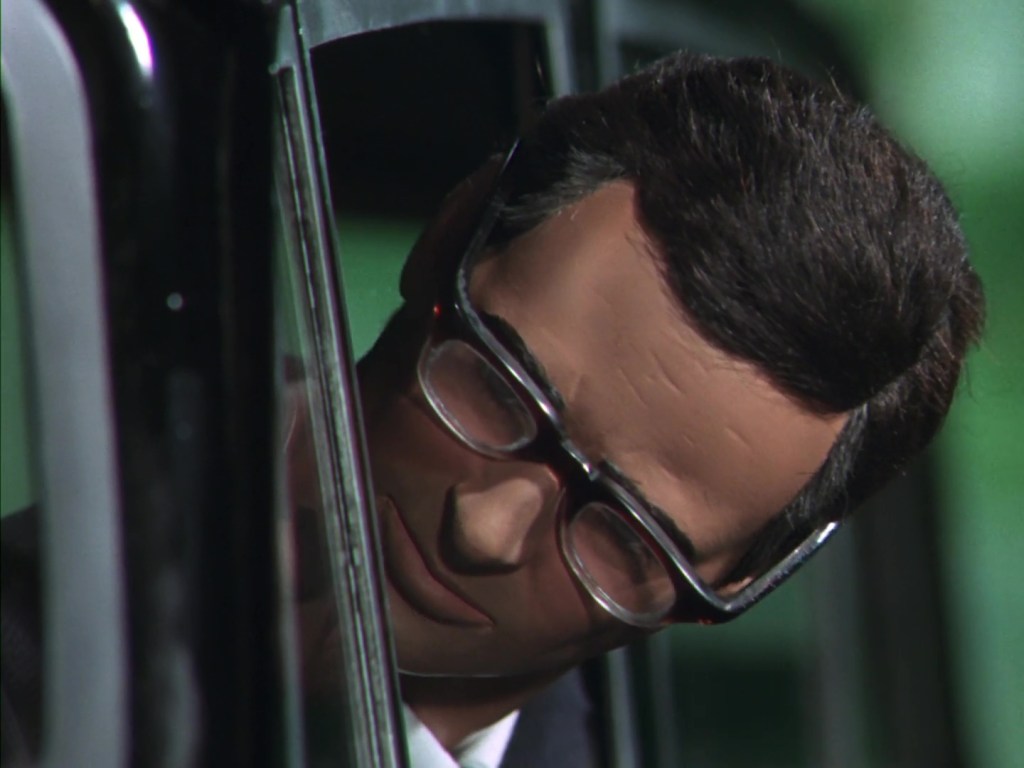

Now then. This is where The Secret Service well and truly breaks its own rule that I mentioned earlier about actors’ faces being kept at a distance while the puppets handle the close-ups. Instead, the real Stanley Unwin has been put front and centre to shatter any and all hope of the illusion working. By looking directly at his face we can tell he’s obviously not a puppet. And it also means that there is no getting away from the fact that the puppet, however realistic it may appear, is still a puppet and not the real Stanley Unwin. What’s even more bewildering is the fact that an unused alternative to this shot was filmed using the puppet, and is available on the textless version of the titles from the DVD release:

The real Stanley Unwin’s face is never shown in close-up again outside of the opening titles. Lesson learned I suppose.

But, why was the decision made to feature the live-action Unwin so prominently in the opening titles at all? There are a number of factors to consider. In the context of this first episode, it actually isn’t all that strange to see a real human face given that we haven’t seen any marionettes during the pre-titles sequence.

Then consider the original script which opens the episode with an excerpt of the car chase from later on, and would have therefore featured the puppet Unwin quite prominently. Perhaps that is why we have the unused puppet version of this window shot so that the two sequences could be married together more seamlessly. When that idea for opening the episode was dropped, the production team might have taken the opportunity to reconsider the title sequence and how they would introduce Unwin.

Now, let’s consider Stanley Unwin himself. If the story is to be believed, the entire format of The Secret Service was constructed around Unwin’s participation. Gerry Anderson met with the comic film actor in 1968 during the production of Doppelgänger at Pinewood Studios, where Stanley Unwin was performing post-sync work for his role in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Unwin was a reasonably well-known name in the UK, and it would seem that Gerry was a fan. So, the thought might have simply been that when you bag a star, you put them in the titles when their name appears on-screen… even if that makes no sense at all given The Secret Service‘s unconventional production techniques.

Across the Buckinghamshire countryside, it’s implied that Father Unwin is gazing out towards his church. It’s a glorious image as the choir of the Mike Sammes Singers swells with angelic nonsense. The title, The Secret Service, descends from the heavens, just to drive home its double-meaning. Unfotunately, the cleverness of the title would be lost on anyone until they actually watched the series, so from a marketing perspective the show just sounds like a pretty generic espionage series. And by 1969, the schedules of ATV Midlands needed yet another ITC spy show like a hole in the head. Department S came back on the air in the Midlands on September 17 following a summer break, Randall And Hopkirk (Deceased) debuted on September 19, and then A Case For The Bishop popped up two days later on September 21. It’s easy to see why a title like The Secret Service might have gotten lost in the mix. And that’s not even taking into account the fact that the schedules across the ITV network were saturated with repeats of all the previous Supermarionation shows too.

As with Captain Scarlet and Joe 90, the key players at Century 21 receive prominent credits. David Lane, who had risen up through the company from the editing department to directing the two Thunderbirds feature films, and subsequently served as the producer of Joe 90 alongside Reg Hill as the executive producer. Gerry and Sylvia Anderson are credited only for the format of the series. They had recently become parents again the previous year with the birth of Gerry Anderson Jr., and Doppelgänger‘s somewhat rocky production at Pinewood Studios was also consuming a lot of their attention. Supermarionation veterans Desmond Saunders and Derek Meddings continued in their respective supervisory roles as they had done for Joe 90, with both men managing multiple units shooting simultaneously. Meddings was also working on multiple productions simultaneously since Doppelgänger‘s model work fell firmly under his jurisdiction.

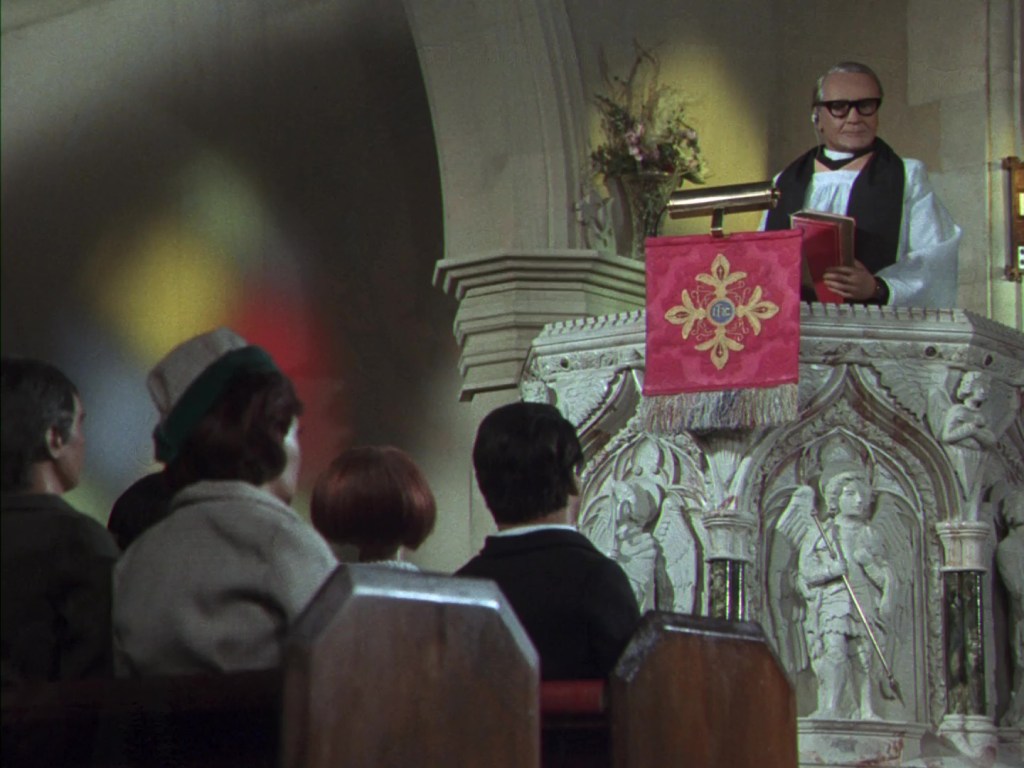

The title sequence itself is less than thrilling. The shots of the Church of St. Michael and All Angels near High Wycombe which serve as Unwin’s parish church are lovely and all, but they don’t fulfill the brief of what a title sequence should do. The espionage aspect of the show isn’t touched upon at all. There’s no action, no intrigue, and no sense of danger from a villain, or a hint of heroism from the regular cast of characters. All we know is that Father Unwin is a priest in the countryside. What’s concerning is that the sequence plays out pretty much exactly as it was written in the script by Gerry & Sylvia Anderson. This uninspired title sequence wasn’t a case of a magnificent vision getting lost in translation or reimagined by the producer or director. Apparently, this was the best the Andersons could come up with.

The one creative spark which saves the whole thing, thankfully, is Barry Gray’s music. The Mike Sammes Singers provide their do-do-do-do-do vocals throughout the series’ score and it’s perfect. If I could only point to one person involved with the production who I think truly understood the series’ tone and the type of stories it should have been telling, it was Barry Gray. His music for The Secret Service is innovative, versatile, quirky, and fun. He absolutely nails the score and dared to make it different from anything he’d done before. I get the sense that while many at Century 21 were yearning for the good old days, or fatigued by the studio’s unrelenting production line, or desperately looking for big motion pictures and live-action opportunities on the horizon, Barry Gray had his whole heart invested in The Secret Service and totally embraced the show’s quirkiness.

London, 1968. In the sunshine. Lovely Morris Minors and Routemaster buses dashing about in the mildest of mild traffic in front of Parliament Square. The original script specified St. Paul’s Cathedral – possibly because the Andersons were fans of the The Power Game starring Patrick Wymark which, guess what, prominently features St Paul’s Cathedral in its opening titles.

Let’s briefly the discuss the production timeline of The Secret Service. While Doppelgänger was shooting between July and October 1968, Stanley Unwin was issued a contract for The Sercret Service on August 20th, 1968, just days after the final episodes of Joe 90 were in the can. (Totally incidentally, this was also just a couple of weeks before the Doctor Who production team would be shooting Cybermen emerging from the sewers in front of St. Paul’s Cathedral on September 8th – I’m not suggesting this is the reason why the location wasn’t used for A Case For The Bishop but you’ve got to admit it’s close!)

It was decided to shoot the location/live-action material first for each episode under the direction of Ken Turner and his newly formed location unit. Turner had previously directed the Joe 90 episode The Unorthodox Shepherd, which shares one or two similarities with The Secret Service in that it uses location filming around a church, and prominently features a country vicar. Shooting on the puppet and special effects stages back on the Slough Trading Estate would then begin to match the location footage and essentially fill in the gaps. Filming inserts before the main action seems a bit backwards in my eyes but according to Ken Turner it was necessary for the Supermarionation directors to know what they were having to achieve in the studio. It also meant episodes from the beginning of the series have noticeably more summery location footage than later ones shot during autumn and winter when daylight was limited.

Anyway, by October 16th, 1968, Barry Gray was recording the opening and closing theme music, and later the score for A Case For The Bishop on November 12th. Scores for three other episodes, A Question of Miracles, The Feathered Spies, and Last Train To Bufflers Halt were recorded on December 11th and January 10th.

The infamous screening of A Case For The Bishop for Lew Grade was held at some point in December, by which point ten episodes were in the can. By Friday, January 24th, 1969, the puppet stages at Century 21 were closed for good once principal photography on the oustanding episodes of The Secret Service was done and dusted. Just six months of shooting from beginning to end, followed by a limited broadcast run in three ITV regions (ATV, Granada and Southern) starting nine months later. One of the reasons The Secret Service is discussed and remembered so little by the production team is probably because it wasn’t a part of their lives for very long at all in the grand scheme of things.

Anyway! Back to the episode, and we’re looking at this particularly tall building in Central London which I have to say is mighty impressive. This is Centre Point, and you can still find it today next to Tottenham Court Road Station. Just look up. You can’t miss it.

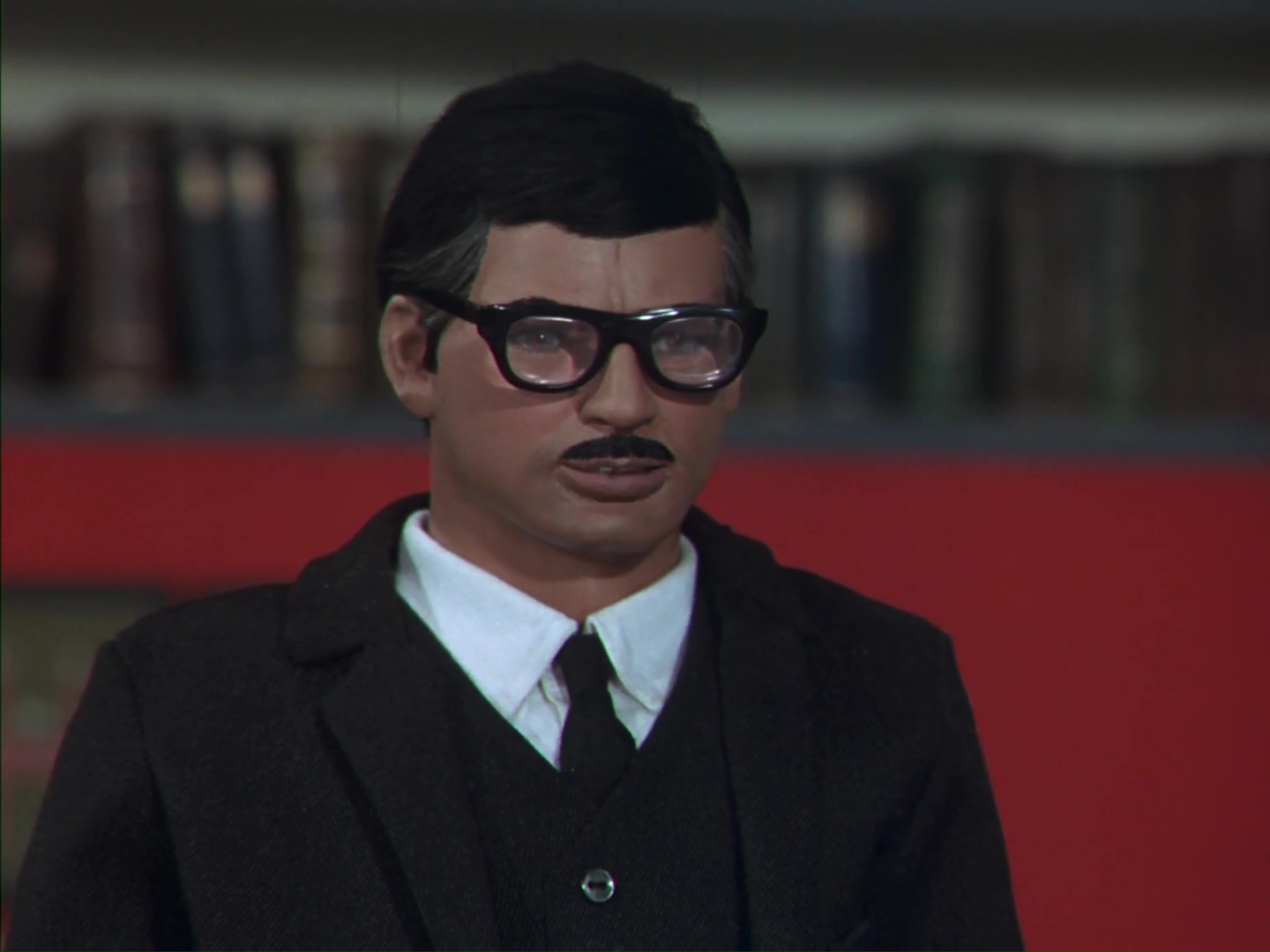

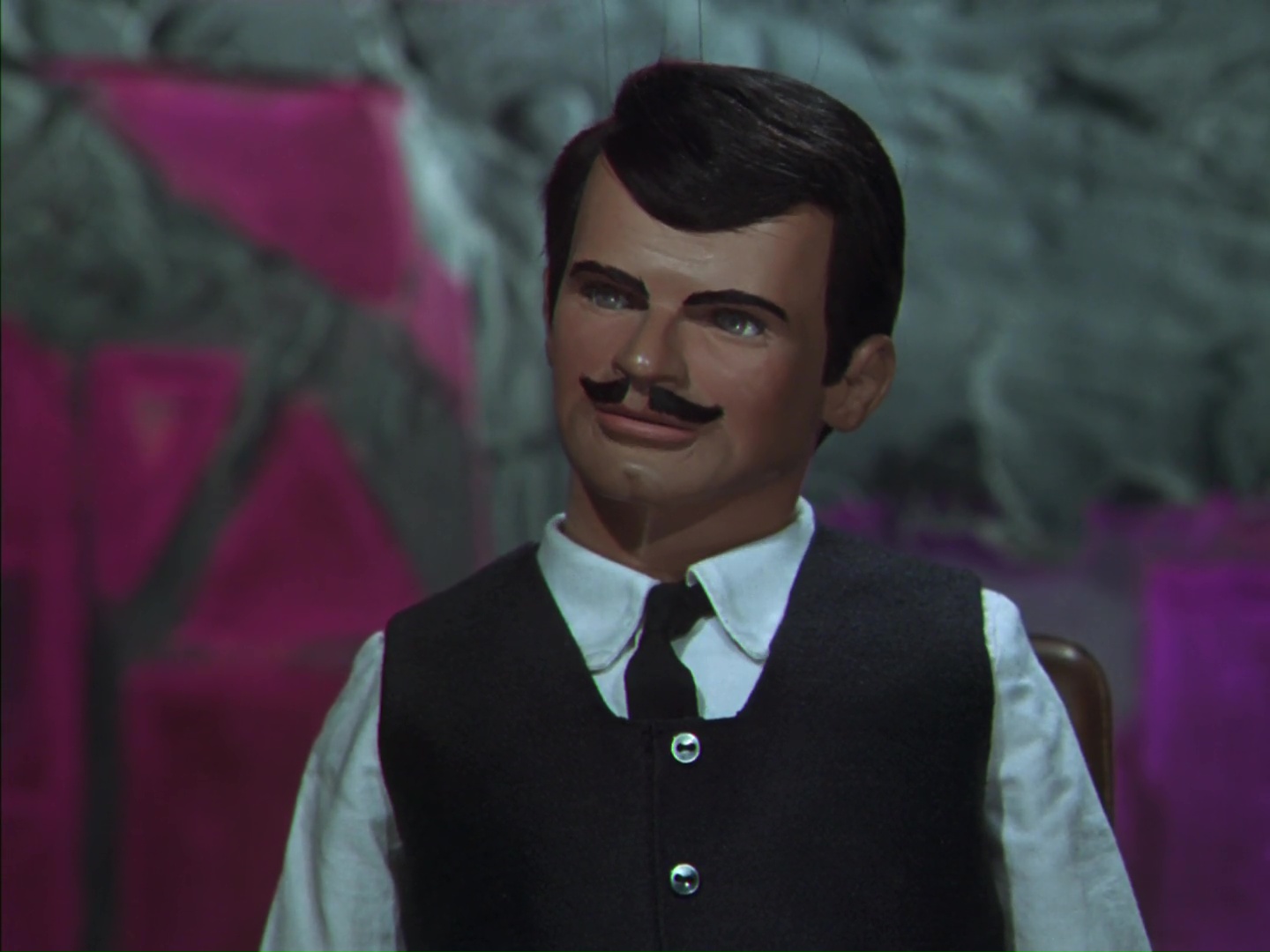

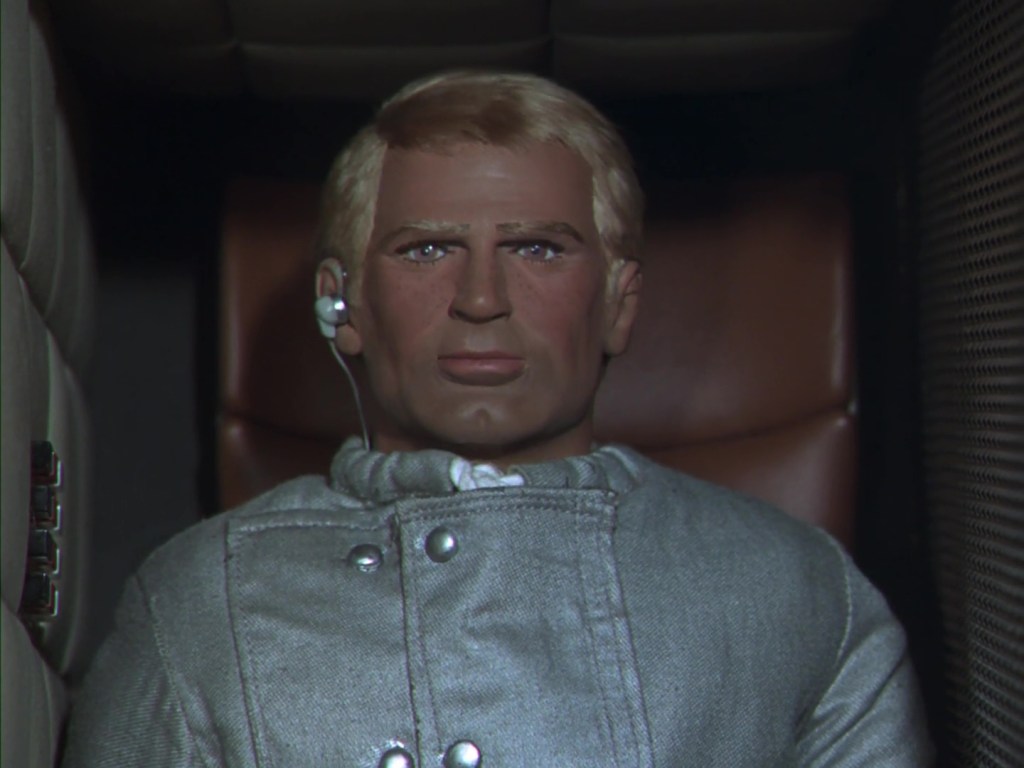

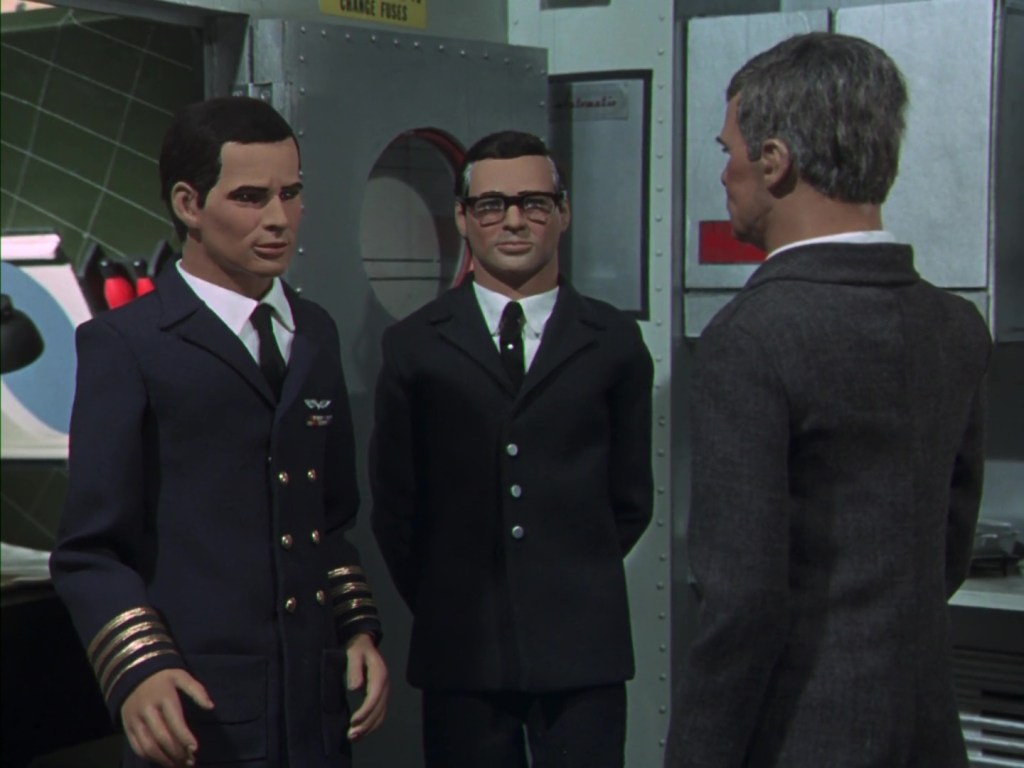

Finally, some puppets. Honestly, now we’ve finally gotten to them there’s nothing particularly remarkable to say. Just like Joe 90, the standard set of revamp puppets in realistic human proportions established for Captain Scarlet was drawn upon for The Secret Service. Cataloguing all fifty-something marionettes and all of their roles across Scarlet, Joe, and The Secret Service has been done across several publications so I won’t re-tread old ground as far as that’s concerned, other than highlighting the significant appearances.

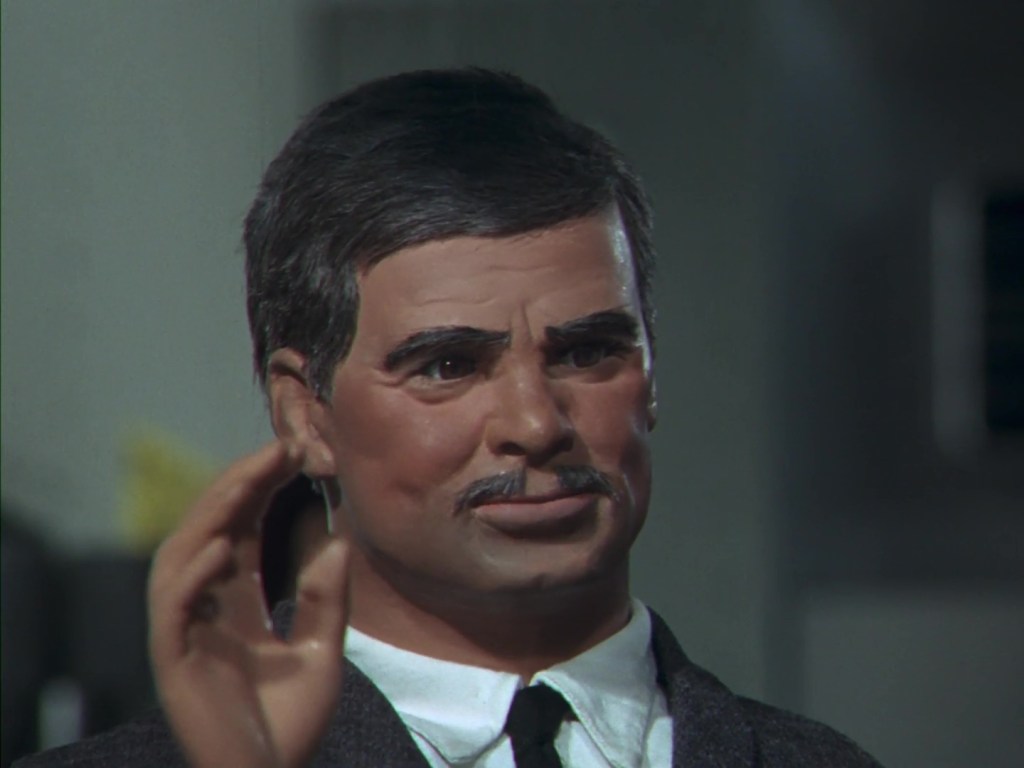

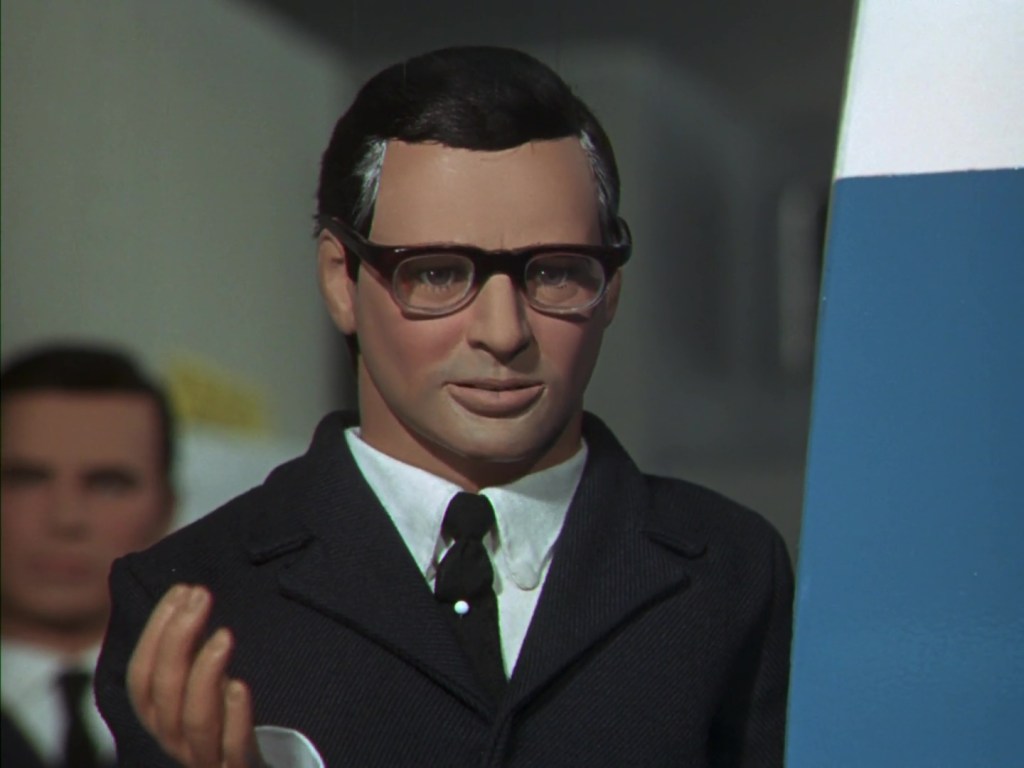

Nigel Patterson, described in the script as “a typically British War Office type” is ranting and raving about the theft of the KX20 minicomputer by Dreisenberg agents. Oh yeah, that’s the plot. Saunders, who is sat behind the desk and portrayed by Doctor Fawn from Captain Scarlet, is described in the script as “the older of the two men and obviously holds an important position.” I think the director, Alan Perry, might have gotten the puppets the wrong way around because Patterson looks older and more important than Saunders here. Saunders and Patterson may or may not have been intended to become a permanent fixture for the series, seeing as they turn up again briefly in To Catch A Spy.

So, apparently the computer is in the Dreisenberg embassy right now and the ambassador plans to fly home tomorrow using diplomatic immunity to smuggle the stolen device out. The script details that Dreisenberg is a fictional “small European community sanwiched between Germany and Austria.” Apparently Patterson is concerned that this will impact Healey Automations (originally named Emmett Automations) and it’s £500,000,000 worth of export orders. They don’t get specific as to how the theft of the computer damages those orders, or how it would in any way be a threat to national security. If this were an episode of The Power Game, Sir John Wilder would have cross-examined some poor twerp over every detail of the political and capitalist minefield that this incident has created, eviscerated those responsible, and then snuck off to smooch with his mistress. The Power Game is a great show, but I digress. Saunders reckons that all this business warrants the attention of The Bishop…

The Horse Guards building between Whitehall and the Horse Guards Parade is the headquarters of the latest super special Anderson organisation. Not exactly Tracy Island, but I imagine the commute is easier.

British Intelligence Service Headquarters Operation Priest. As Anderson acronyms go, I think BISHOP is brilliant and whacky in equal measure. Presumably the British Intelligence Service is the equivalent of the real-world M.I.6, although I doubt an operation of that size would fit inside the Horse Guards building. Presumably Horse Guards is just the headquarters for Operation Priest, as lead by…

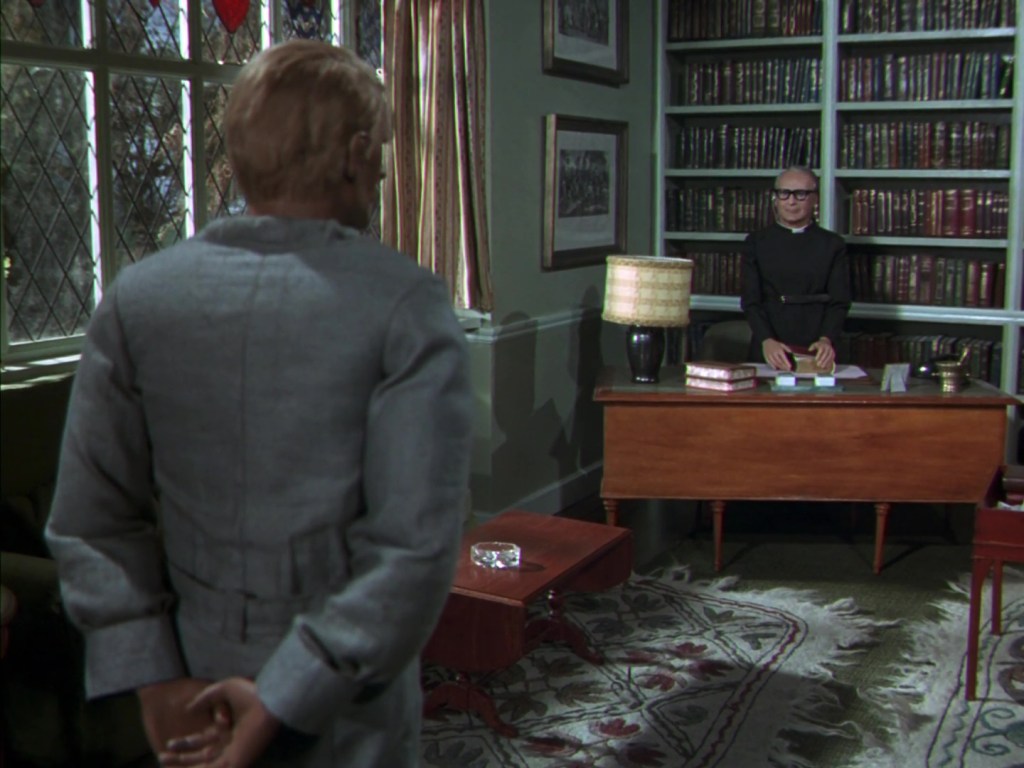

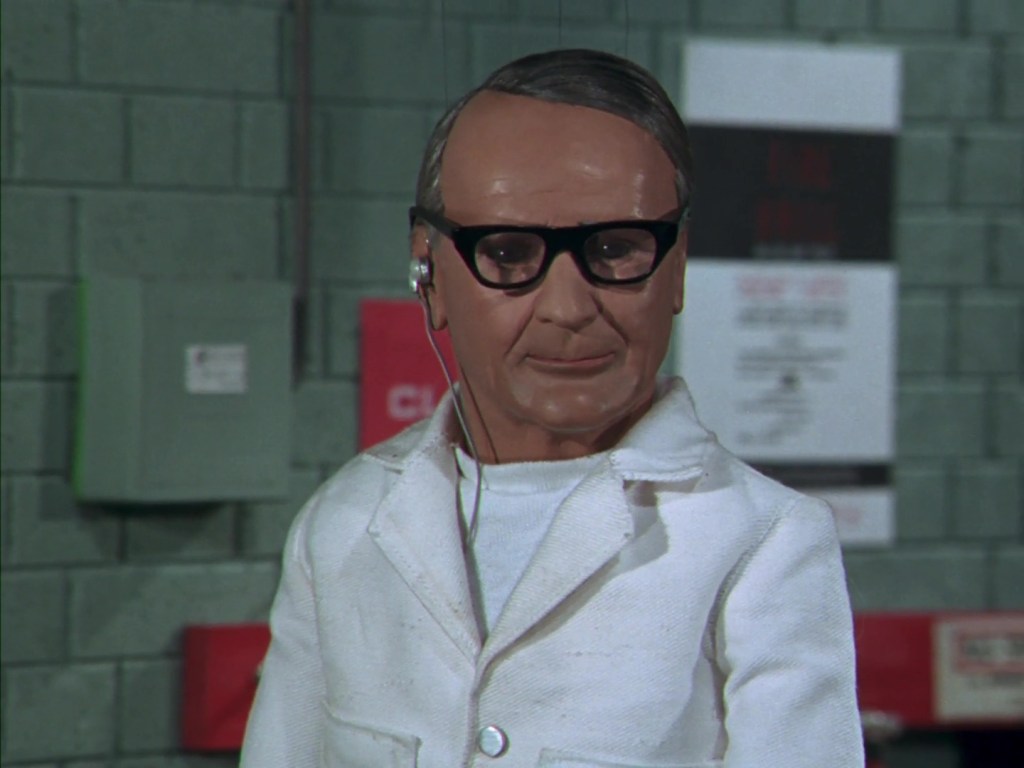

The Bishop. Yes, BISHOP is run by The Bishop. Try not to get confused. This is his office. It looks like every civil service office in Whitehall ever. Although to be fair I can’t see a drinks cabinet.

Voiced by Jeremy Wilkin, The Bishop is one of only three new puppets created especially for The Secret Service – the other two being Father Unwin and Mrs Appleby who we’ll see in a few moments. The voice seems to be based on the likes of Sir John Gielgud. His gentle tone makes him instantly likeable rather than stuffy and dull as his surroundings suggest. The character always seems to carry a magical air of mystery about him. We never learn his full name but we do get some tantalising insights into his long career with British Intelligence throughout the series. He isn’t given much to work with in this first episode, but the writers soon got a good grasp on how best to use The Bishop and make him an interesting character.

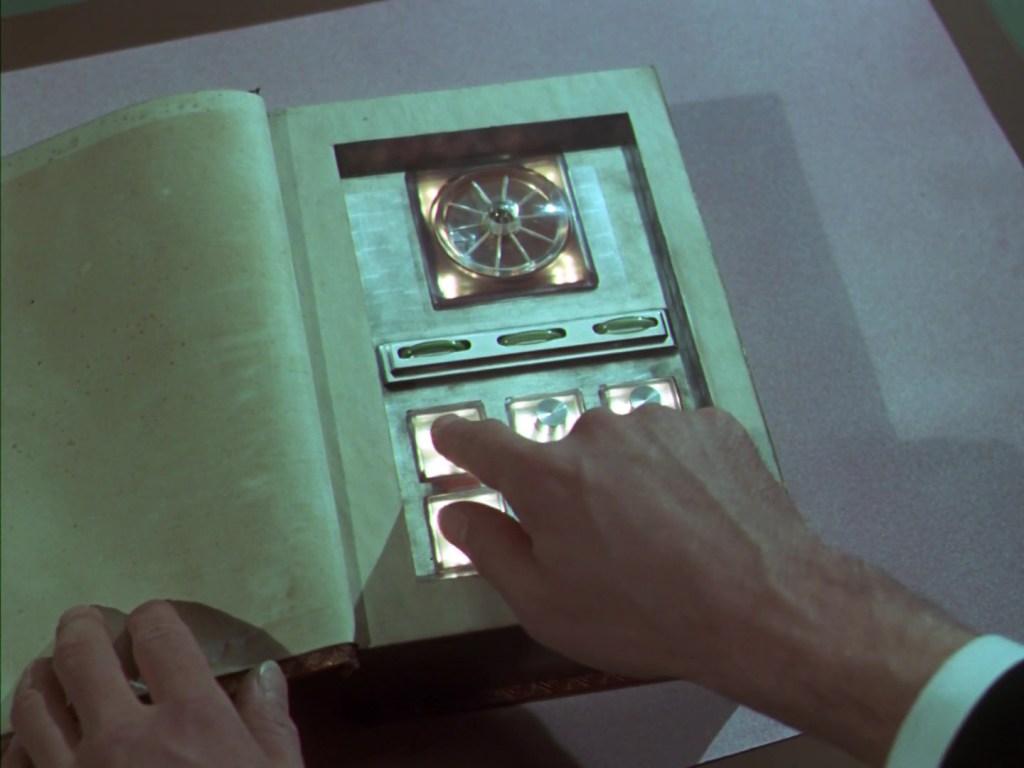

He activates a scrambler device on his desk as soon as the call from Saunders comes in. The puppet-sized version of this prop survives to this day, while the live-action prop was simply a real office switchboard with the “Agents” label stuck on. Presumably this means that Father Unwin is agent 3 and being patched in to the call, and there are at least 8 agents of BISHOP in total.

Cut to the vicarage and we get to meet the star of the show, Father Stanley Unwin – the puppet. He’s seated on a bench in his beautifully manicured back garden. This does, however, immediately flag one issue with cutting back and forth between real-life locations, and exterior puppet sets built in the studio – the lighting varies wildly. Supermarionation puppets and sets have to be lit in a very harsh and precise way in order to achieve an up-sized depth of field. No matter how sunny it is, the real outdoor location footage can never look so vibrant. Also, outdoor locations are always moving with trees rustling, clouds gliding across the sky or tiny flickers of birds and wildlife in the far distance. The miniature puppet sets can’t easily replicate that because everything is so much smaller and produced artifically. The result is that everything suddenly becomes very static and lifeless in the Supermarionation world. There’s nothing wrong with the way either shot looks when viewed seperately, but you’d struggle to fool anyone into thinking they were filmed in the same place.

Father Unwin receives communication from the Bishop via his hearing aid as he looks to the sky, seemingly talking to a higher power up above – a gag which is laid on much more heavily in the original script. The Bishop says that interception (of the minicomputer presumably) must not take place at London Airport. Not sure why. Even the script just sort of skips over that bit, but I guess it’s to keep the plot moving.

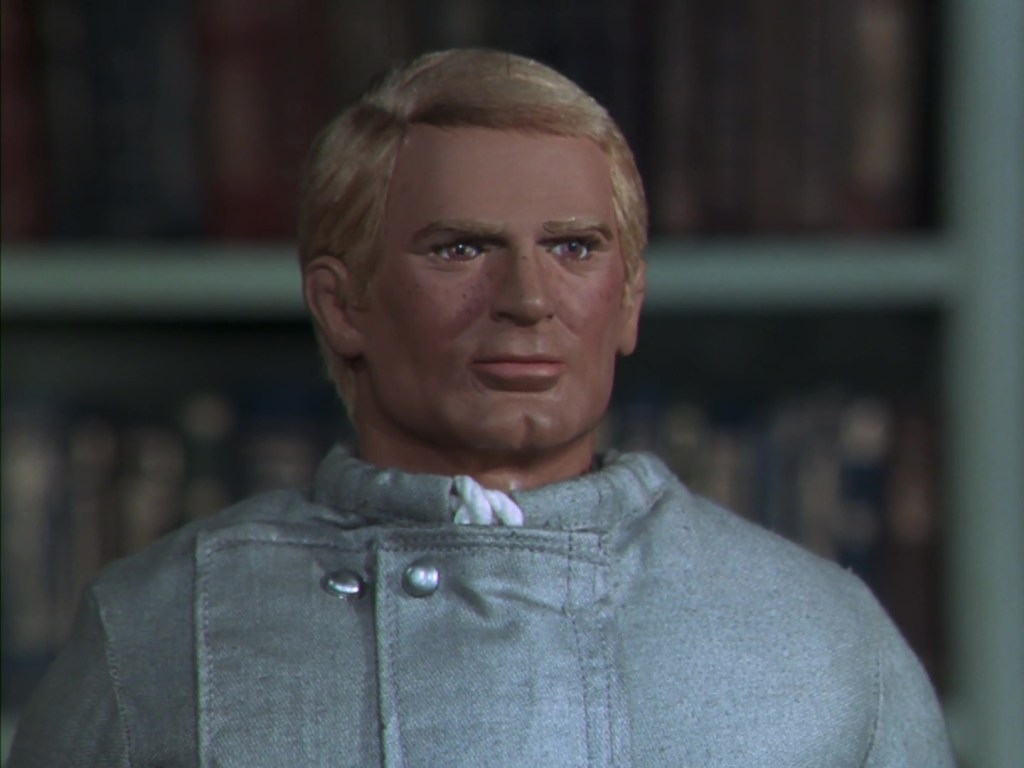

Let’s take a proper look at the Father Unwin puppet, scultped as it was by Mary Turner to be a perfect clone of Stanley Unwin himself. It’s good. Really good. Really, really good, in fact. It’s about as perfect as it possibly could have been given how teeny-tiny the heads of Century 21’s realistically-proportioned puppets were. When the team had Supermarionation-ificated Cliff Richard and The Shadows for Thunderbirds Are Go, they had much larger canvases to work with because the puppet heads were almost twice the size.

Of course, the curious thing about choosing Stanley Unwin to Supermarionation-ify (yes, I am trying to coin that term) is that he was a comic actor with a very expressive face. In fact, I’d say it was the mad, joyful, highly animated expression of his eyes and mouth that really sold the use of his Unwinese gobbledygook when he was performing. So, capturing a static expression of him which is neutral and suitable for a variety of scenes, was never going to result in a perfect outcome. The way the real Stanley Unwin gets his mouth around certain words and how his eyes glimmer as he does so simply can’t be captured in solid fibreglass and electronic lip sync.

It’s worth noting that Century 21 had essentially abandoned the concept of swapping heads on the marionettes to convey different emotions because the sculpts were too small to achieve any major differences in facial expression… and also emotions weren’t so much of a thing in the scripts for the later puppet shows, let’s be honest. But I don’t think a range of expressive heads would have saved the Unwin puppet from appearing a little too stiff and joyless to pass for the real man himself.

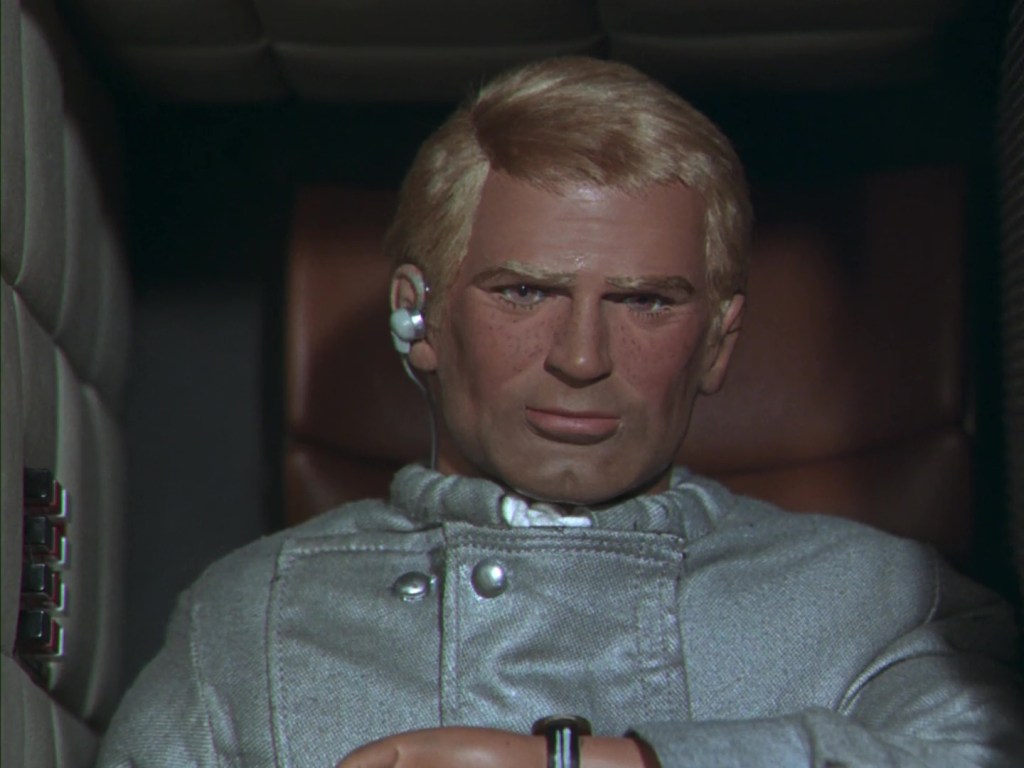

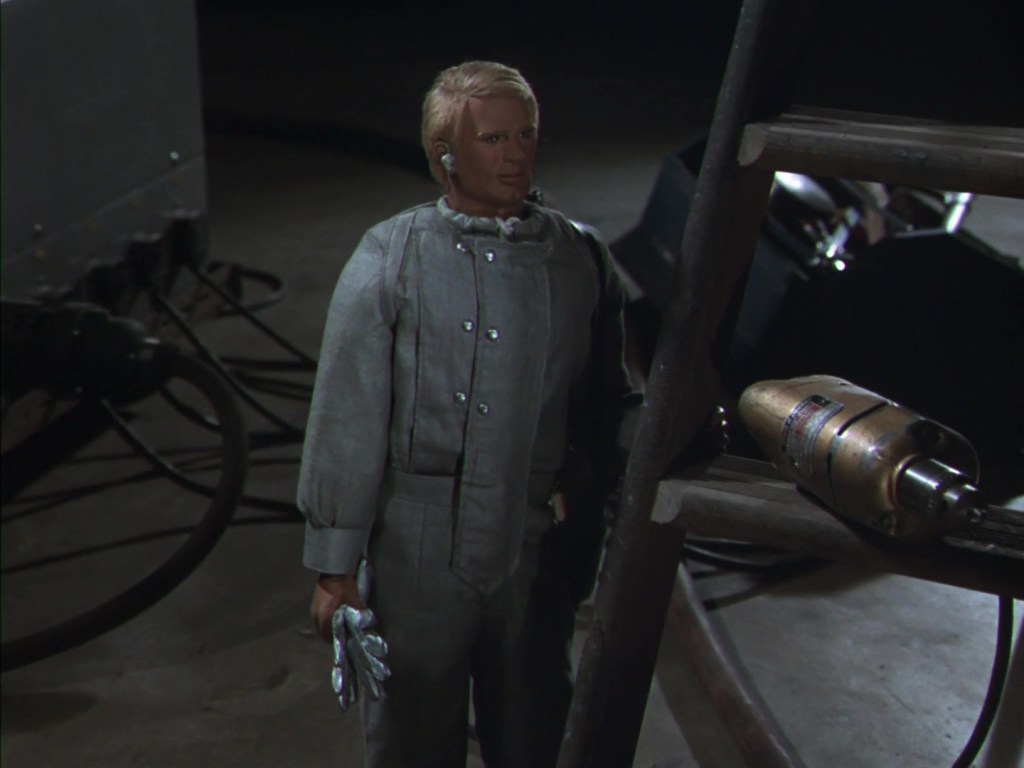

Time to introduce another character! It’s Matthew Harding, Father Unwin’s gardener and aide de camp. This character was created from a revamp puppet originally seen as Dr. Mitchell in the Captain Scarlet episode Treble Cross, but now wearing a blonde wig. He is voiced by Gary Files, who starts by giving him a country accent. Yes, regional British accents are a thing in The Secret Service. It seems that after Thunderbirds, the rules were slightly relaxed at Century 21 in regards to everything having to appeal to American audiences at all costs. Francis Matthews played the titular Captain Scarlet with an English accent, and Joe 90 is lead by the slightly cockney Len Jones, and the well-spoken Rupert Davies. The Secret Service is almost exclusively populated by British and European characters which feels like a very unprecedented course-correction given Lew Grade’s ambitions to sell to America at all costs in previous years. Ultimately, at its core, The Secret Service has a very British premise. Unlike previous Supermarionation series, I don’t see how anything could have been done to convince Americans that they were watching an American show unless the fundamentals of the format were changed. This is so clearly the case that the logical conclusion is that the Andersons had essentially given up, at least with the The Secret Service, on trying to appeal to Americans.

Coming back to the voice cast and it seems particularly odd that the format should require so many British characters when the Andersons had put so much effort into gathering a repetory of international voice artists for their shows, many of whom stayed on for The Secret Service. Keith Alexander and Gary Files were Australians and David Healy an American, while Jeremy Wilkin was originally hired for Thunderbirds based on his career in Canada. Of course, the Andersons had a good working relationship with these actors by 1968 and it was probably easier to keep using them on the off-chance one or two trans-Atlantic characters turned up in the scripts, than to hire new actors. All of that being said, I do think the voice cast are wonderful and capture the Britishness of the series superbly, perhaps better than an all-British cast would have managed.

It soon becomes clear that whatever Father Unwin is keeping secret, Matthew is in on it. Matthew is a rather likeable and dynamic character. He’s a young man who takes himself quite seriously, but he has a certain dark wit and charm which gives him an edge. Matthew is designed to fit the more conventional, young, and handsome hero archetype that one might associate with the British Intelligence Service. While Father Unwin fits right in to his country parish and is the last person you’d expect to be a secret agent, Matthew is the amusing antithesis to that. Matthew looks like a spy and makes for a very unconvincing gardener to the point that even the blissfully ignorant Mrs Appleby suspects something is up, as we’ll see later.

The Roseate Hotel opposite the Forbury Gardens in Reading serves as the location of the Dreisenberg Embassy (thank you Google Lens). At the time of filming in 1968, the building was actually known as Shire Hall and was the home of Berkshire County Council – now it’s a 5-star hotel and has been spruced up quite considerably.

This scene is not in the Andersons’ original script for the episode and was likely added due to the change to the opening pre-titles sequence. Had the show opened with the chase sequence as planned, we would have already been introduced to the Dreisenberg Ambassador and his aide before we next see them on the plane. Instead, this exchange at the embassy quickly introduces them and also lets us know that the security guard from earlier did survive but isn’t doing so good. I know you were all concered about that.

David Healy is a master of voicing nasty, generic, European men and gives the phrase, “British FOOLS” a big helping of disdain. The Ambassador taps his precious minicomputer with an awful lot of smugness. One very much has to infer that he’s stolen the KX20 in order to damage Britain’s trade deals and open up Dreisenberg for a share of the cash, but none of that is stated outright. To be quite honest, the plot of this episode feels like something of a formality. It’s not exactly a life or death situation. In fact it’s barely even a cause for distress.

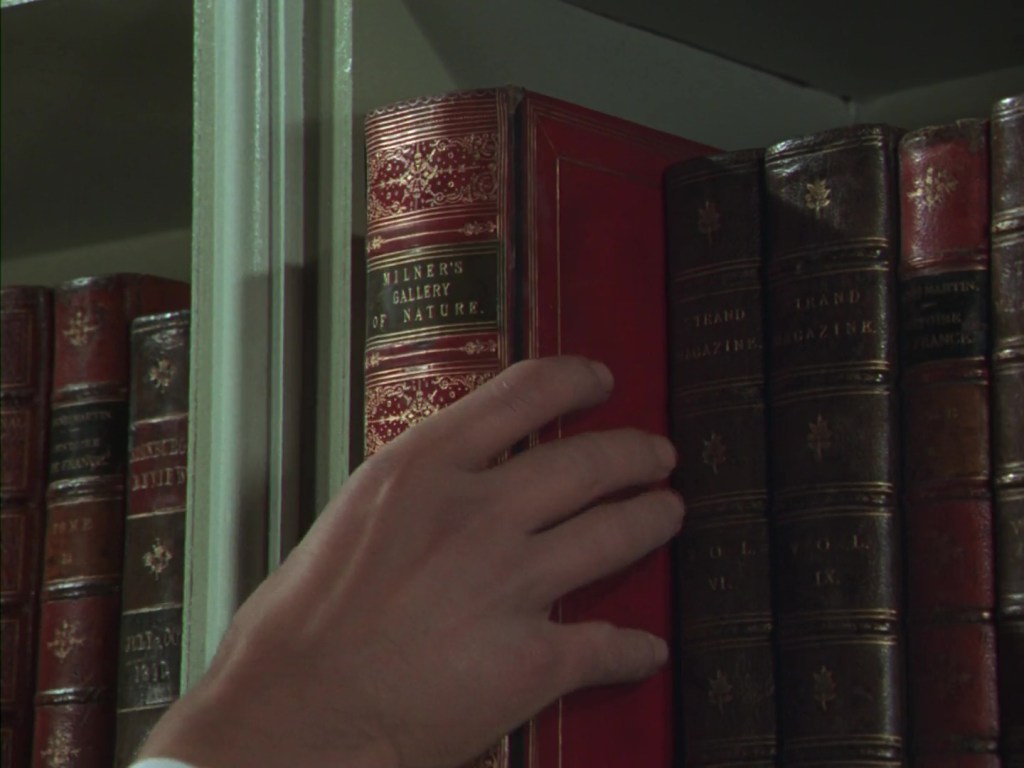

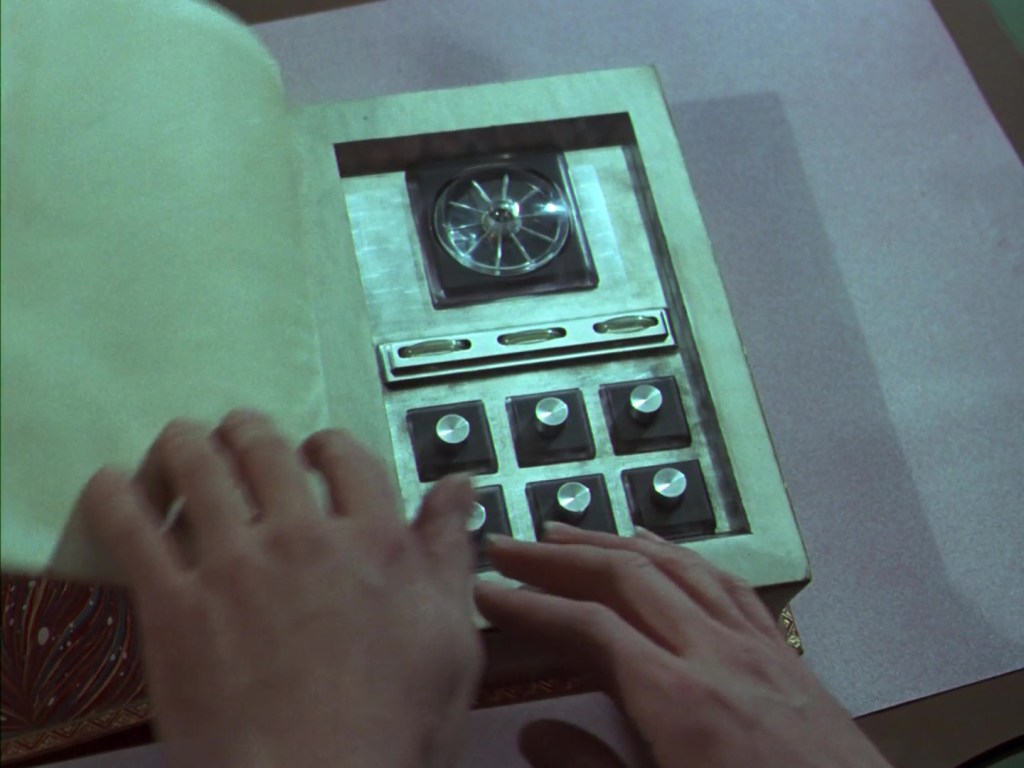

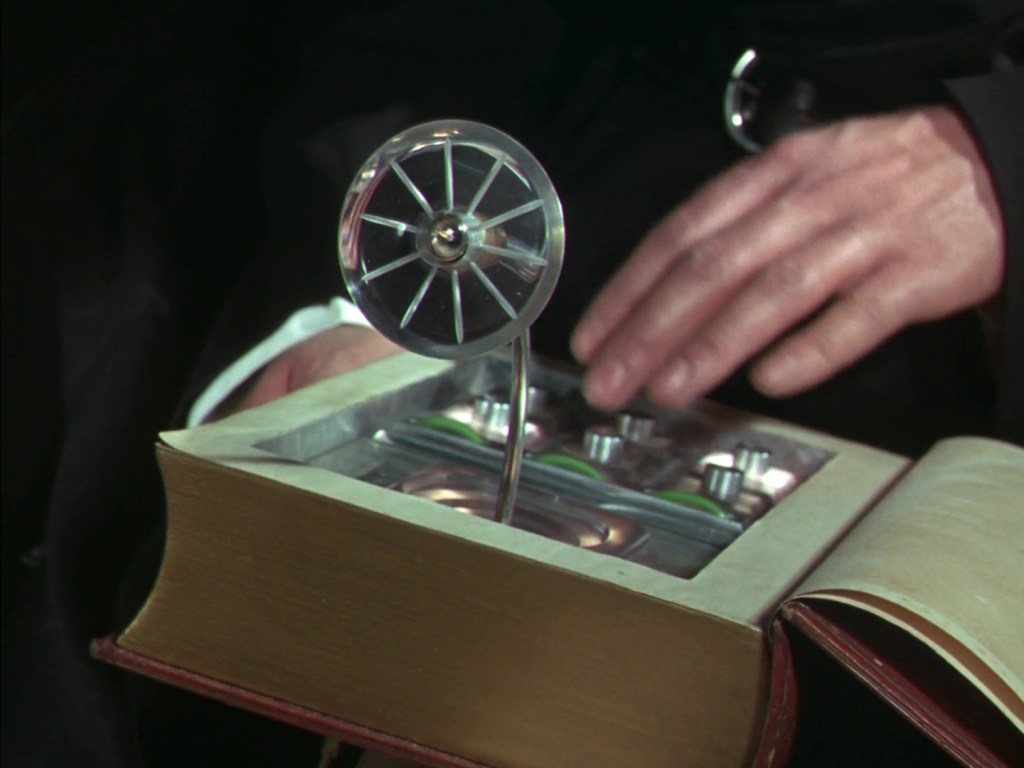

Back at the vicarage, Father Unwin extracts Milner’s Gallery of Nature from his bookshelf. I’m guessing that book was chosen for the simple reason that the script specified a “large red book” and that one fitted the description best. Unwin opens the book to reveal the Minimiser concealed inside. It may just be a few buttons and shiny things but I like the Minimiser. It’s an elegant and sophisticated little device and the fact we really don’t get any explanation as to how the darn thing works doesn’t really bother me. However, I can also appreciate that compared to the much more developed “scientific” concept of the BIG RAT from Joe 90, the Minimiser can come across as a bit of a rushed idea for the benefit of the series’ format.

Strap yourself in for a bit of a shock, but it turns out Matthew isn’t really a country bumpkin. I know, I don’t think I’ll ever recover because the act was so convincing. It turns out he’s quite a well-spoken, cultured fellow who probably thinks that poor people should be in a zoo. At least that’s the vibe I’m getting here, I could be wrong.

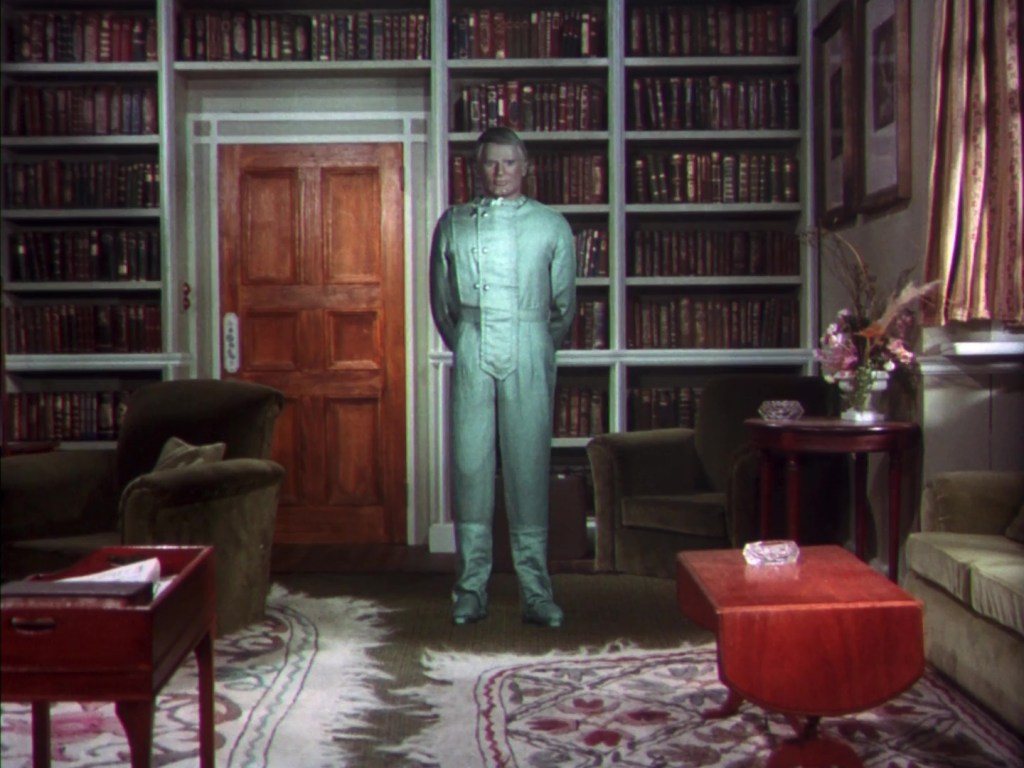

Father Unwin activates his miracle machine and the music, bright light and whizzy sound effects do most of the heavy lifting to convince us that something very exciting is happening. According to Gerry Anderson’s DVD commentary for this episode, the technique used to achieve Matthew’s shrinking on-screen was a closely guarded secret… which probably translates to “clever optical printing thingy that would take too long to explain.” Of course, by today’s standards the effect looks rather flat and cartoony, but I think it works well enough and later scripts tended to work around not showing this particular moment too often.

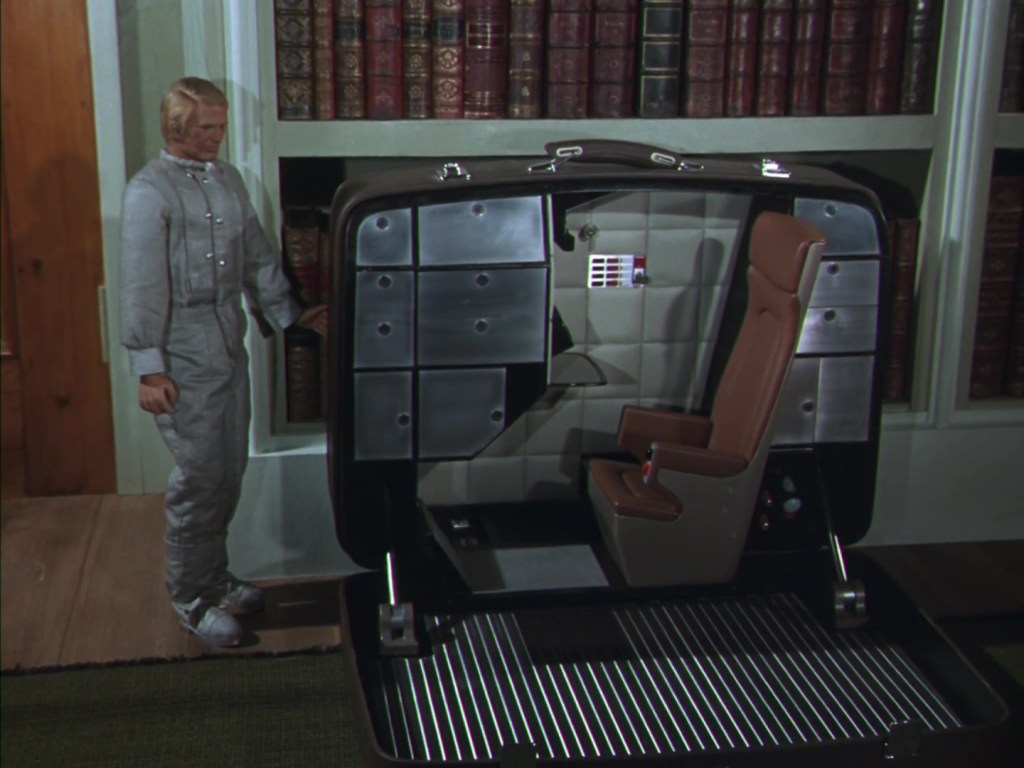

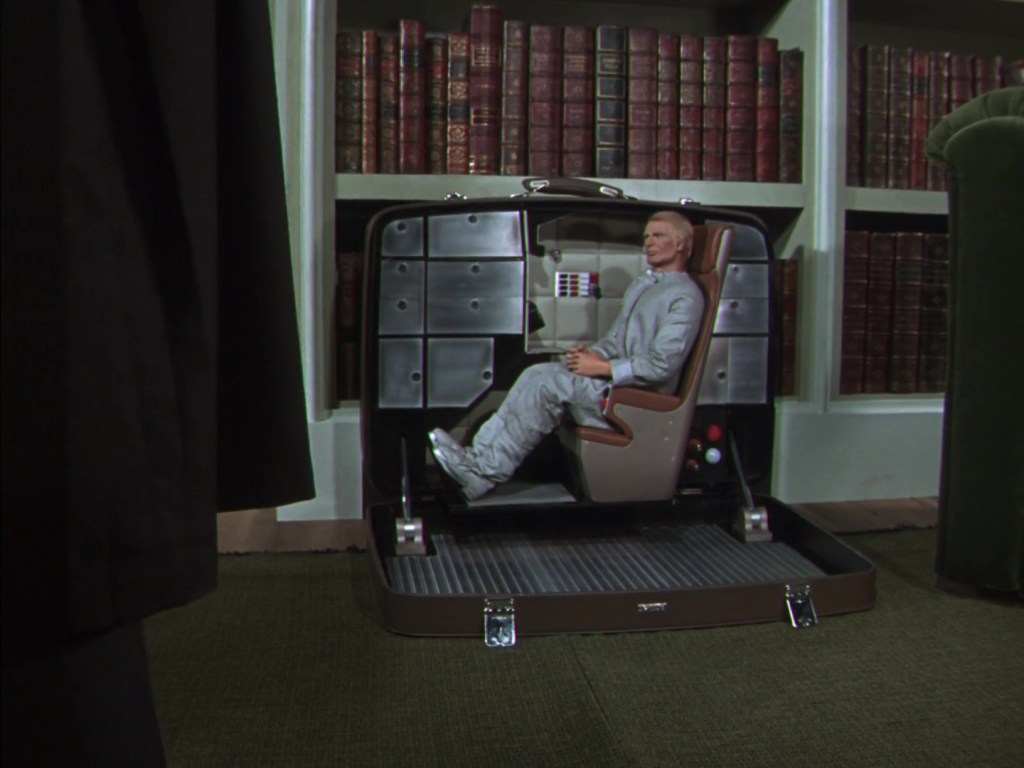

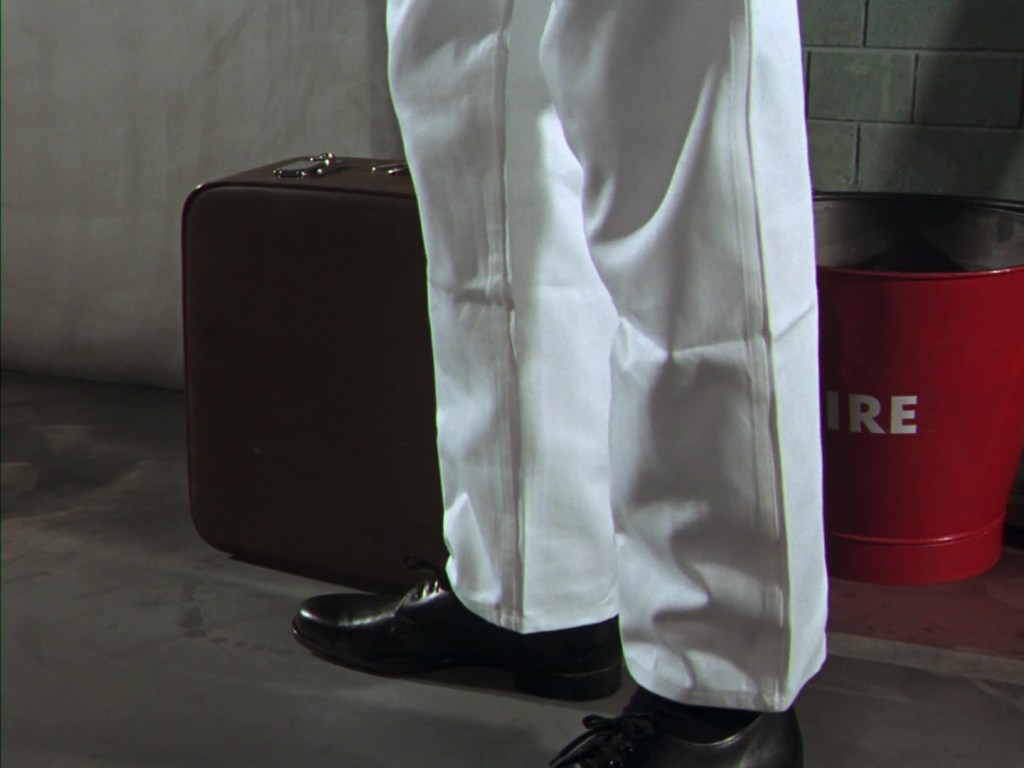

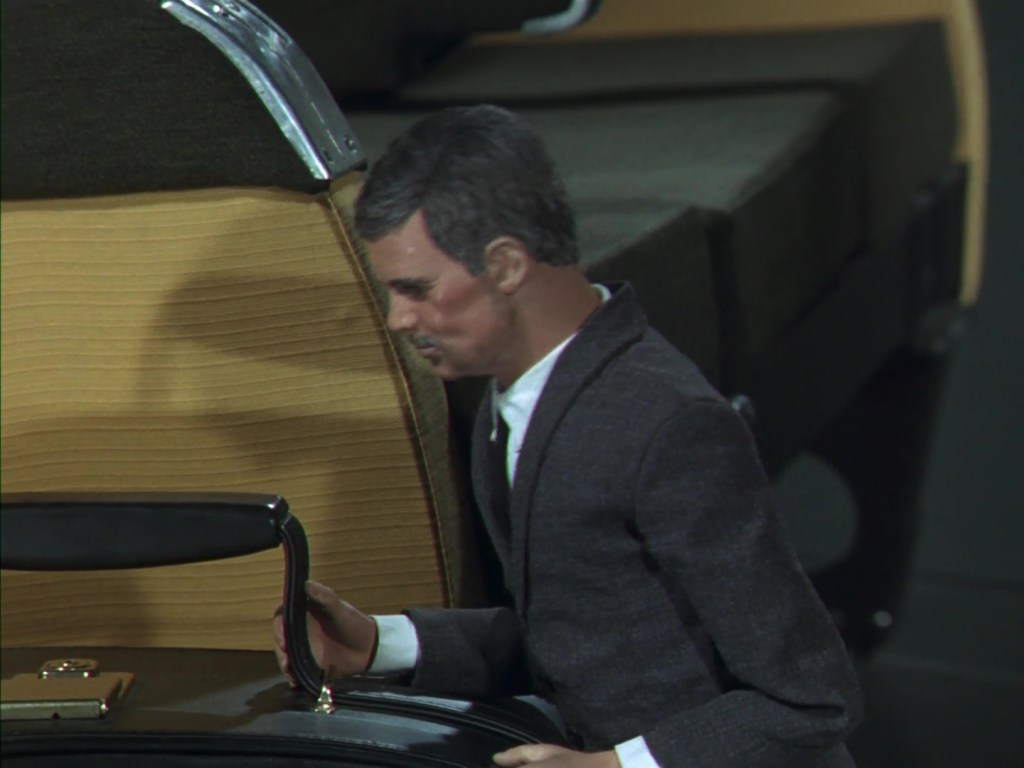

And so, the gimmick of the series really comes into play now. With Matthew reduced to one-third of his normal size, he can undertake covert missions completely undetected with the help of Father Unwin and his ultra comfortable and high-tech suitcase. This also means that the puppet of Matthew could interact with all the real-life locations and actors that were used throughout the series. So now we’re not just talking about cutting between Supermarionation and live-action, but actually integrating the two in the same shots… Needless to say the puppet of Matthew still looks very much like a puppet when stood next to a real person.

Matthew shuts himself in the case and Unwin tests their radio communications. It’s never stated on-screen or in the script one way or the other, but I’d like to imagine that A Case For The Bishop is Father Unwin and Matthew’s first mission together. That would explain why certain aspects, such as the protracted the radio checks, are being emphasised for the audience’s benefit. Having said that, Matthew is clearly an experienced agent because – well he just seems like the sort. As for Father Unwin, who knows how his recruitment to BISHOP came about. Was he a secret agent first and a priest second? Or was he an ordinary vicar who acquired the Minimiser and was then signed up to the British Intelligence Service? So many questions, and bog all in terms of answers unless you consult the handful of spin-off books and comic strips for the series.

This here is the meat and potatoes of what Stanley Unwin was hired to do for the series. Driving around the countryside in Gabriel, keeping his face at a distance. As the viewer settles in to the constant back and forth between puppet and live-action, the whole thing does become quite charming. Some audiences probably have a better tolerance for it than others.

Now, let’s talk about Gabriel, the yellow Model T Ford which is the only starring vehicle of the series. It’s probably the most beloved icon of The Secret Service but it’s also a clear indicator of the show going in a vastly different direction to its predecessors. No futuristic vehicles that screamed “BUY ME” to toy manufacturers – although bless Dinky, they still gave it a go. It’s interesting to remember that science fiction was originally something of a means to an end for Gerry Anderson. The invention of Supercar and the star vehicles which followed was necessitated by the fact the puppets couldn’t walk convincingly in Gerry’s eyes. By eliminating that issue with live-action inserts of Stanley Unwin and others doing all the walking, there was also no requirement to fill the series with high-tech equipment to travel from place to place. Heck, the one character in The Secret Service that does stay puppet-sized gets carried around in a suitcase. But Gabriel, in its colourful livery, symbolises that the Andersons still valued their star vehicles as characters in their own right. Gabriel could have just been a Morris Minor or any other standard motor vehicle available at the time. But the bright yellow 1917 Model T is something special and it became an attraction for the series, just like Stingray or Fireball XL5 had been in the past. Gabriel is just a different, more quirky take on that same star vehicle formula and I think it’s a perfect fit for The Secret Service.

A puppet-sized version of Gabriel had to be built, of course, for all the dialogue scenes and it’s an incredibly detailed and accurate prop. Live-action back projection footage is used to convey the countryside sweeping by which means, for once in a Supermarionation production, the stuff we see the puppet drive past actually matches what the vehicle itself is driving past. Matthew observes via a periscope in the case. The motion sickness from being chucked around in a suitcase all day long would make me hurl. Apparently, “provided the traffic’s not bad” they should make it to the airport within half an hour – Heathrow in 1968 must have been a very different experience to the way it is now.

Just in case you’ve forgotten what an airport looks like, here’s a handy reference shot.

The script, and indeed the dialogue, specify that we’re at London Airport – which is noteworthy in the sense that London Airport was renamed to Heathrow Airport in 1966 and for some reason the Andersons decided to stick with the old name.

Gabriel sitcking out like a sore thumb amongst the traffic is really delightful. Ultimately, this whole sequence represents exactly what Century 21 were trying to achieve with The Secret Service and the way in which it uses live-action. There’s a terrific energy to this material and it particularly appeals to viewers today because it offers up a real slice of 1960s life, rather than the artifical retro-futuristic bubble of the studio-bound Supermarionation shows. Barry Gray matches the energy of the sequence perfectly with his composition and although it’s taken us a little while to get there, I feel like we’ve now reached peak Secret Service. For all their previous pilot scripts, Gerry & Sylvia Anderson had generally been good at giving us some spectacle at the start to hook us in – and indeed their original pre-titles sequence featuring the car chase would have provided the same thing. But the final version of A Case For The Bishop takes a little longer to get going and that might be a problem for Supermarionation fans demanding some visual satisfaction from the word go.

Here’s an odd bit which attempts to contribute a little more quirkiness to The Secret Service‘s style. Described in the script as a “Chaplain like interlude,” Unwin enters some cloakrooms and some jaunty piano kicks in while time speeds up. Some happy 1960s-type summer-lovin’ people go about their day before Unwin emerges again dressed as a service technician. It juuust about works but I do have a few issues with it. Too much time passes and not enough people are seen going by to really sell the idea that Father Unwin is quickly and covertly blending in with his surroundings. A man just walks into a building, gets changed in what might as well be real time, and then walks out looking just as conspicuous as he did before. This is one of the downsides of Stanley Unwin having to keep his performance incredibly neutral and uninteresting in order to match the capabilities of his puppet counterpart. A performer with Unwin’s expressiveness and comic timing could have made a big, entertaining thing out of that joke, but instead he’s forced to play it totally straight and can’t match the whimsical tone of the scene. Such overtly comic sequences weren’t really attempted again during the series.

I do find that, if I’m not paying close enough attention, these live-action sequences do start to wash over me and I don’t actually notice their impact on the plot. My brain is trained to watch Supermarionation shows in a certain way which includes the fact that live-action shots are usually just a means to an end that briefly interrupt the plot to show us something that a puppet can’t do with its hands or feet or whatever. So when presented with masses of live-action material like this, I don’t necessarily take it in. For example, this is the first time I’ve realised when watching A Case For the Bishop that Unwin steals a car to drive to the aircraft hangar, and that the pair of legs we see under the aircraft is not Unwin, but just a random person going about their day to demonstrate the new setting we’re in. All of that sounds really obvious now that I say it but it’s taken years for me to process for some reason.

Matthew gets popped down next to a fire bucket and we can finally cut back to a puppet. Again, such lengthy live-action sequences weren’t really attempted again during the series without cutting back to the puppets every so often as well. The longer we spend looking at real people, the more jarring it is when the marionette pops back in.

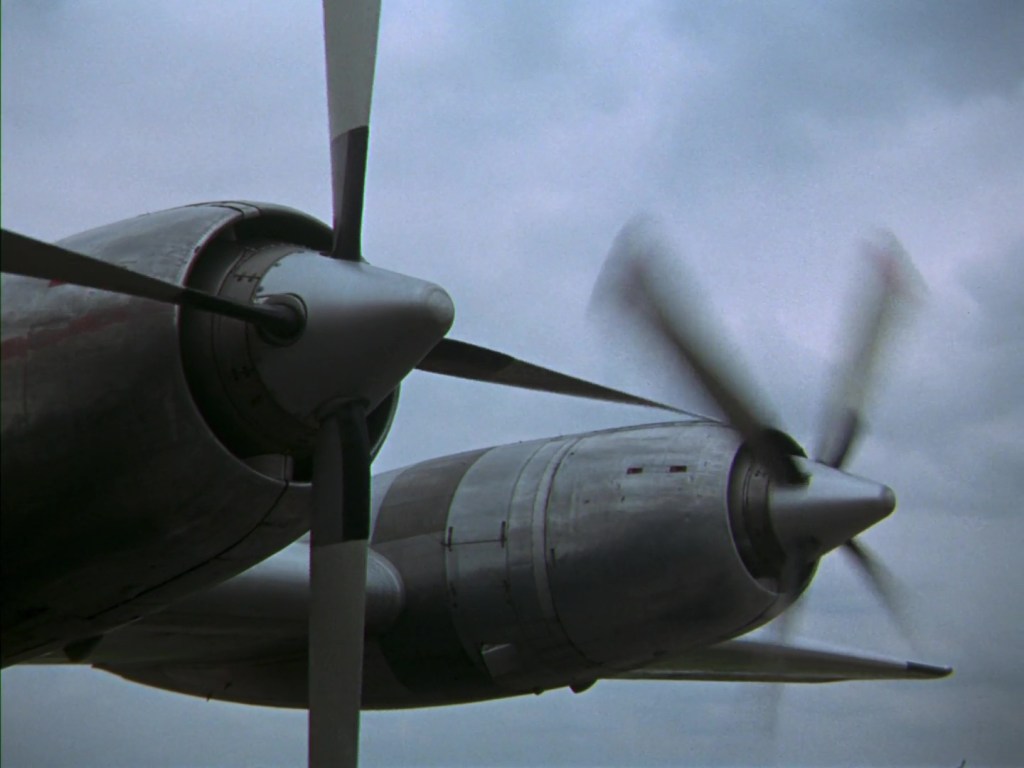

At last! A model shot! Yeah, there’s no getting around the fact that the Century 21 special effects department got handed a pretty rubbish deal when The Secret Service came along. Replacing all those futuristic vehicles and fantastical action sequences with contemporary cars and planes interacting with very ordinary surroundings meant that their involvement was limited to the stuff that really couldn’t be done on location. Now, when considering the series as a whole, the special effects team do get some interesting things to do in later episodes. Unfortunately, A Case For The Bishop‘s very pedestrian plot and intense emphasis on location filming definitely made the effects team surplus to requirement. It is somewhat baffling that the Andersons spent years, alongside Derek Meddings, forging the finest special effects department in the world and developing specialist buildings and facilities on the Slough Trading Estate with lots of time and investment behind them… only to come up with a TV format which barely utilises any of them. Fortunately, Derek Meddings’ crew was still responsible for the more ambitious effects work on Doppelgänger, and then UFO went a little ways to give them something exciting to do with futuristic vehicles again. But the introduction of live-action meant that their lifespan and usefulness was henceforth limited.

The Secret Service also presented the effects team with an entirely new problem. Previously, the Supermarionation puppets and the miniature effects had inhabited the same artificial world. Now, the models had to sit comfortably alongside real-life locations and vehicles. Century 21’s miniatures were incredibly detailed and realistic, but fundamentally it was impossible to perfectly match the lighting of a model shot taken in the studio to an outdoor location shot, or to get lightweight miniature objects to behave exactly like they had in adjacent shots of the real thing on location. The format was actively working against the illusion that model effects were there to achieve.

One other thing to consider in all of this is budget. Now, the numbers surrounding the cost of Supermarionation productions vary wildly depending on who you ask so take some of this with a pinch of salt. The 1995 Century 21 Script Book reports that the budget per episode of The Secret Service was £20,000 as opposed to Captain Scarlet‘s princely sum of £50,000 per episode, while according to Thunderbirds: The Vault, the budget for Thunderbirds‘ first series was reportedly increased from £25,000 to £38,000 per episode when each show was extended from 25 to 50 minutes. Whatever the exact numbers involved, and without straying into a lecture on the history of 20th Century economics, there’s no getting around the fact that costs had probably risen to keep Century 21 operating, while the returns from each new Supermarionation series since Thunderbirds had diminished.

I can’t help but feel that maybe some of the creative production choices that were made for The Secret Service were in place to keep the team in work without breaking the bank. Live-action elements produced on location meant that the costs of running the model shop would have been reduced. Meanwhile, continuing to favour filming puppets for the bulk of the material avoided the costly effort of adapting the studios to accommodate full-sized soundstages and protected the investment that had been made in the specialist Supermarionation facilities. At the end of the day, a television series has to be profitable to sustain its existence, and the change in Britain’s economy lead to some interesting decisions being taken right across ITC’s output when the UK’s economic boom of the 1960s became a malaise in the 1970s.

Matthew and Father Unwin part ways by synchronising watches. Now all that Matthew has to do is wait in his suitcase until midnight… which is still about 6 hours away… I’ll let you guess what an athletic young man does for 6 hours when sat alone in a suitcase. Also Dreisenberg has its own airline so it can’t be doing so badly that it needs to resort to corporate espionage, surely?

Funny how 12 midnight looks an awful lot like 12 noon when the crew are shooting day-for-night. For those of you not in the know, shooting on film at night is extremely fiddly (that’s a technical term), so instead of doing that, everything is filmed during the day with as little of the sky showing as possible. The camera’s exposure is reduced and a blue tint is added. In my humble opnion it’s about as convincing as Matthew’s West-Country accent.

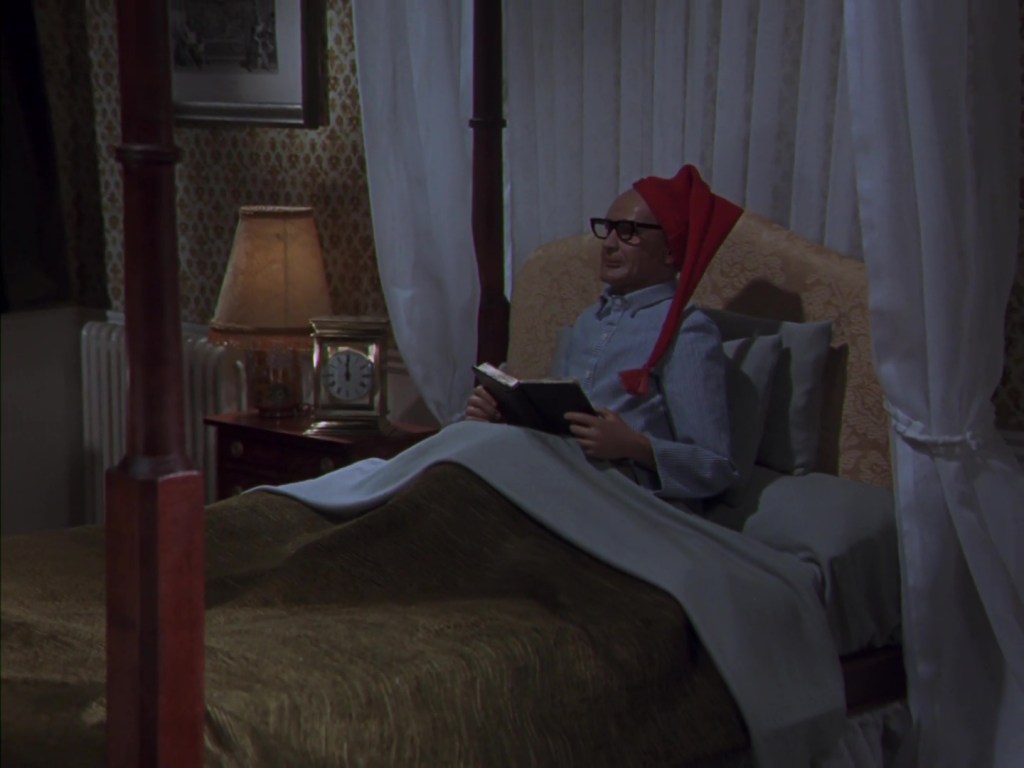

The interior of the vicarage is delightful, as are many of the lavish puppet sets seen in The Secret Service. It’s worth noting that Keith Wilson had recently risen to become the series’ sole Art Director since Bob Bell was working on Doppelgänger and Grenville Nott had become the manager of the Location Unit. Wilson would go on to produce some absolutely stunning set designs for Space: 1999.

Meanwhile, Iris Richens in the wardrobe department obviously felt like having a bit of a laugh when she came up with that bright red nightcap for Father Unwin. In fairness to her, the original script does insist upon it, but still, do me a favour.

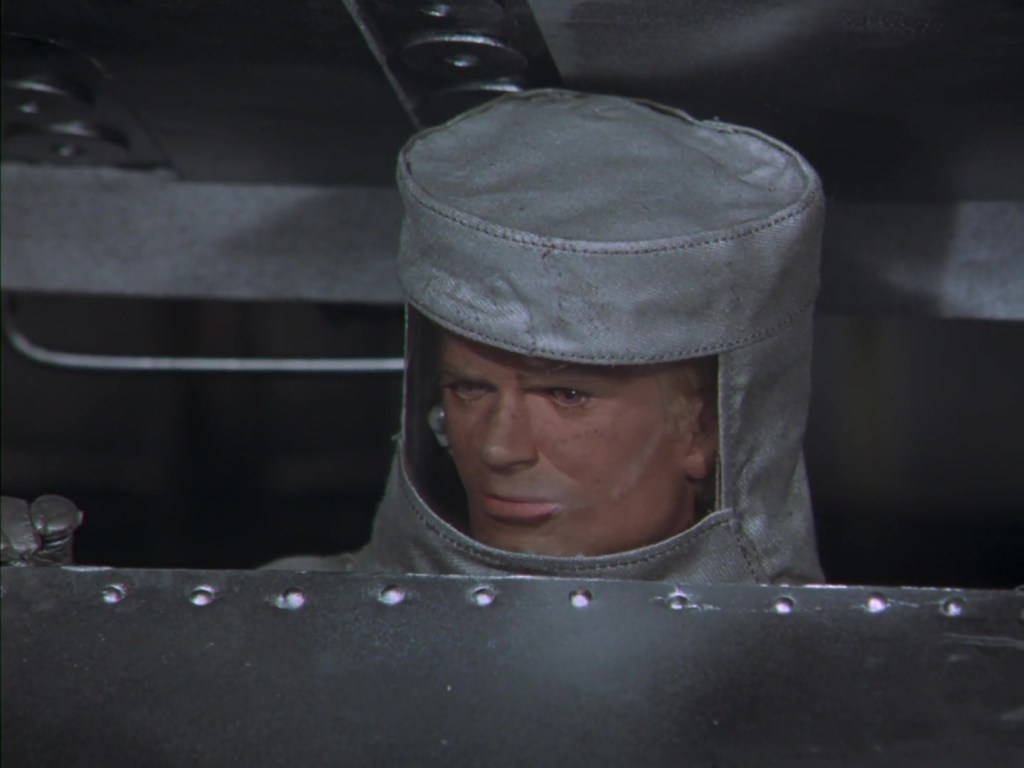

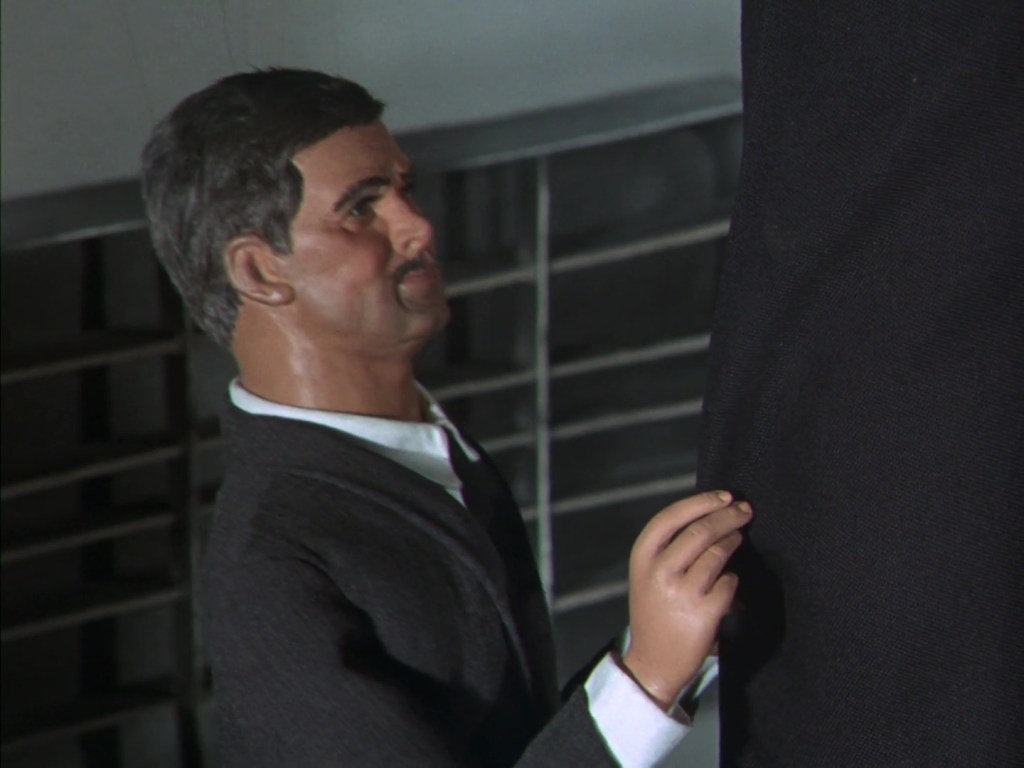

It’s time for Matthew to emerge from his case and this lovely shot is achieved with the puppet set in the foreground and the miniature set in the background. You can actually see the distinctly wooden edge of the model set if you look between Matthew’s back and the seat. It also looks like this Matthew puppet is being controlled from underneath rather than by wires above. The under-control Supermarionation puppets were introduced during the production of Thunderbirds Are Go and were commonly seen in Captain Scarlet and Joe 90 for scenes which required the puppets to be positioned underneath something such as a cockpit canopy in the case of the Angel pilots. Their movements were generally stiffer and more immediate than the wired marionettes operated from above, but in the right context the under-control system can be very effective.

Matthew makes his way over to inspect the aircraft, with his long walk concealed from the audience by cutting away to Father Unwin because… well, puppets can’t walk… which is hilarious considering the incredible lengths that were now being gone utilising live-action to reduce that exact issue. Apparently the cowling for the engine being open is perfect for Matthew’s objective. We aren’t told what that objective is yet, which is probably a good thing since explaining the plan to the audience before doing it can get tedious. Presumably the Matthew puppet is standing on the real studio floor next to a real studio ladder which the puppeteer might even be working on top of. The script emphasises the specialist equipment that Matthew has with him for the operation – “wearing his fireproof suit and carrying oxygen cylinders draped over his left arm.” Apparently the oxygen cylinders weren’t considered so important for the final episode.

Bored of the rather uninspiring conversation he’s having with Matthew, Father Unwin decides to go to sleep in a movement which can best be described as a floor puppeteer awkwardly trying to keep out of shot. Apparently the next call won’t be until 09:00 hours so I guess that means Matthew gets to spend the next 9 hours snoozing in an engine… whatever BISHOP pays him for this stuff, it’s not enough.

While Father Unwin enjoys a scrummy breakfast, poor Matthew confirms that he’s getting ready to cook himself on the aircraft’s engine… or at least he will in an hour’s time when the plane is due to take off. Yes, Matthew gets to hang around for another hour. Patience of a saint that lad.

Mrs Appleby, the vicar’s housekeeper, arrives on cue armed with a feather duster. According to the script, “She is a round, plump jolly lady with rosy cheeks and grey hair pulled back in a soft bun. She is a typical homely, country type, with a very slight country accent.” Christine Glanville sculpted the character to resemble her own mother and it must be said that she’s probably one of the most beautifully detailed Supermarionation puppets ever created. Sylvia Anderson provides the voice for the series’ one and only recurring female character. She’s given slightly more to do than Mrs Harris from Joe 90, but it’s still a far cry from the representation of women that had proved so successful in Thundebirds and Captain Scarlet. That being said, Mrs Appleby is still a wonderful character who is given a gentle if naive rapport with Father Unwin. Material cut from a couple of points in this episode’s script would have seen Mrs Appleby and the vicar playing more with the double meaning behind Father Unwin talking to someone “up there.”

Sorry to be “that guy” but… oh goodness I can’t believe I’m about to say this… have you seen how gorgeous the detail is on that radiator in the background? Someone put a lot of effort into making that puppet-scale radiator and I’m in awe of it. There, I’ve said it. That’s how much of a boring twerp I am. I hope you’re pleased with yourself.

Finally, the plane is getting ready for take-off. It’s now 10 o’clock in the morning and Matthew’s been on his own in that fire suit for sixteen hours so I hope someone miniaturised a bottle of deodorant for him. The special effects unit get to be a little more involved now with some miniature shots of the Bristol Type 175 Britannia aircraft which is named “Helga” if the nose of the plane is to be believed.

Meanwhile, the Dreisenberg Ambassador and his aide are delighted to be flying home with the computer. Diplomatic immunity apparently prevented the authorities from searching their cases. I did one of my trademark five-minute internet searches on the subject of diplomatic immunity and yes, diplomats are immune from airport security checks and the laws of other countries. That being said, they are not immune from the laws of their home countries. Unless theft is perfectly legal in Dreisenberg, the Ambassador is still being a naughty so-and-so and could be charged upon the insistence of the British government since they clearly know it was him what done it. Of course, the implication is that Dreisenberg is rather corrupt and would allow it anyway… and just to remind you, Dreisenberg is a fictional state and definitely wasn’t a lazy stereotype for Eastern European nations at the time…

And away they go. Not exactly Fireflash lifting off is it?

Somehow Matthew survived being turned into mincemeat by the engine and only has to raise his voice a little louder than normal to be heard over the Proteus 765 roaring inches away from his head.

Finally, Father Unwin is getting off his backside to do some work and decalres that, “the time has come!” Cue side-splitting confusion from Mrs Appleby while she’s popping the vicar’s clean underpants on the washing line. I appreciate that the religious quips and nods and winks of The Secret Service are never intended with any malice or mokcery, and don’t feel forced or hamper the storyline. Father Unwin’s parish and beliefs are merely a backdrop, and I don’t think they have any bearing on the outcome of the episodes one way or another except to add a little colour.

One more quick bit of, “nothing can stop us,” business from the Ambassador leads us into the commercial break. Still not really feeling the big dramatic tension to be honest, but I am curious to see what Matthew plans to do exactly…

Another dramatic launch sequence for Gabriel. Instead of turning left, Unwin turns right. What a thrilling twist!

Unwin has calculated that the plane is over Oxford… which it is. We get a lovely shot of Magdalen College which may or may not be stock footage. Everything is going swimmingly.

Oh here we go. It’s time for that scene.

You all know the story. As soon as Gerry screened this scene for Lew Grade, the great television impressario stopped everything and cancelled the series on the spot because Stanley Unwin’s trademark gobbledygook language would be incomprehensible to Americans. That’s where the story of The Secret Service always ends. After that, it was just a matter of weeks before the puppet stages in Slough were closed for good.

It neatly sets this scene up as a pivotal and dramatic moment in the epic tale of Gerry Anderson’s television career. Is that really how it happened though? Was the finger of blame pointed directly at Stanley Unwin talking nonsense for just over 30 seconds of screen-time?

The arguments for that story being true are rather outweighed by some bits of simple logic. Yes, Lew Grade was known to be prickly and spontaneous. In fact pretty much every story Gerry ever told about him involved great outbursts of either joy or rage. There are others who corroborate the story that Lew never believed in written contracts such The Prisoner star, Patrick McGoohan. The anecdotes shared by many present Lew as never one to get bogged down by details. ITC was just fiercely keen on selling shows to the American networks, sometimes at the cost of common sense (see Space: 1999 Year 2). So, it goes without saying that whilst Lew’s impulse to cancel the series based on a few lines of dialogue might have been irrational, it does fit the slightly impetuous and foolhardy character of TV’s Lew Grade.

The trouble is, the whole argument falls apart when you just ask – why not remove the Unwinese scenes and reshoot them? It rarely accounts for more than a minute or two of screentime and the likes of script editor Tony Barwick had immense experience with Thunderbirds as far as performing impossible re-writes were concerned. Sure, it would have negated having Stanley Unwin involved with the series, but Lew, great entertainment mogul as he was, must have known what he was getting into as soon as he learned that Unwin was attached to the project. Why not stop the series before it started instead of 10 episodes into production? I know Lew was hands-off, but I doubt ATV was unknowingly wasting hundreds of thousands of pounds covering the production costs of The Secret Service without some idea of the show’s main selling point? It’s not impossible of course; big companies drop the ball on things all the time.

But, hypothetically, if the big Unwinese-bashing cancellation story was so illogical to be untrue, then what did happen? Well, we don’t know and can only speculate. It’s entirely possible that Lew did terminate the screening early and cancel the show on the spot but his reasons might not have been quite so straightforward as hating one particular aspect of the format. Lew may have held a distaste for the whole premise of The Secret Service and Gerry simply boiled the problem down to the Unwinese when re-telling the story in order to save face or get a few laughs from fans. It also squarely lays the blame for The Secret Service‘s diminished status at Lew Grade’s door, rather than all the factors Gerry might not have been aware of or liked to admit.

Lew was likely mindful of including Supermarionation oversaturating the TV schedules (as brilliantly documented in Stephen La Rivière’s Filmed In Supermarionation book). He also would have been well aware of Gerry and Sylvia’s clear desire to switch to live-action. Then there was Lew’s own failure to sell any Supermarionation shows to an American network since Fireball XL5, and the rising costs of producing the puppet films combined with their unsatisfactory American sales might have made them financially unviable. All of that may have simply lead to Lew deciding not to prolong the inevitable.

I’d also like to float the possibility that, given how quickly production of The Secret Service wrapped up between the fateful screening and the puppet studio’s closure, that maybe the series was only ever planned to run for 13 episodes – at least that might have been the initial commission. After all, I’ve never heard any record of scripts for the series going unfilmed, or being left semi-completed. Thirteen is a very common number of episodes to produce for a TV series to fill roughly a quarter of a year. The Secret Service‘s core premise was so incredibly English that I doubt there was ever any intention of running the series to the required length for American syndication.

So, with all that make-or-break behind-the-scenes business said and done, how well does the actual scene itself between Unwin and the police officer play out? Rather nicely I think. Unusually for Supermarionation, much of the dialogue seems to have been improvised between Stanley Unwin and Jeremy Wilkin’s police officer character which results in the uncommon occurrence of the two speaking over each other in a very natural rhythm. The puppet characters in previous shows are rarely seen interrupting one another because the electrical impulse from the dialogue couldn’t be switched from one marionette to the other that quickly by the lip-sync operator. While the Andersons’ script provides general suggestions for what Unwin needs to say in the scene, the nuances of the conversation are left to the actors. It’s played really nicely and the dumbstruck policeman blindly going along with what this incomprehensible priest says fits very nicely into the charming, easy-going atmosphere that The Secret Service tries to conjure up.

It could and probably should have been cut if it would have saved the series from cancellation, but to be honest, I don’t think this infamous scene was quite the nail in the coffin that the history books seem to suggest. The Secret Service‘s relative brevity can be attributed to all manner of factors that are so complicated, it’s easier for those recounting the story to just blame it on the old bloke talking nonsense and call it a day…

Back in the air, Matthew is suitably impressed with Father Unwin’s masterful methods for dodging a speeding ticket. Unwin is now being escorted by the police to Oakington Airport – an airfield which, in real-life, was operated by the RAF between 1940 and 1974.

Matthew can finally put his plan into operation and he fiddles about with something until the inner-port engine cuts out. Ideally, an aircraft needs all its engines to be running when in-flight, so the flight crew (including Captain Ochre from Captain Scarlet) decides to cut the trip short and head back to Heathrow. Very sensible.

The aircraft starts banking and dips down below the clouds to signify it’s turning around. You can’t just whack a plane into reverse and do a three-point-turn after all.

Our loveable theiving diplomats aren’t too happy about it and the aide plans to go and give the pilot a stern talking-to.

Not entirely satisfied by the prospect of going back to Heathrow, the boys decide to get really fiesty and Matthew switches off the port-outer engine as well. The shot of the props cutting out is clearly filmed while the aircraft is static on the ground. Incidentally, the Bristol Britannia had something of a history of engine trouble.

Captain Ochre is having none of it, and puts out a “May-Day” call to London Airport… although the phoney European accent makes it sound more like “matey, matey, matey,” so maybe he’s just really good friends with the air traffic controller.

Dramatic zoom in on Heathrow’s old control tower which was demolished in 2012.

Fortunately, matey-boy is keeping a cool head and directs them towards Oakington Airport for an emergency landing. Remember, of course, that Gerry Anderson served his national service at RAF Manston in the control tower, so this sort of thing was all very familiar to him, and is probably why airfield control rooms feature in the pilot scripts for Thunderbirds, Joe 90, and now The Secret Service.

Father Unwin and his rozzer chums pull up outside Oakington Airport ready to receive the plane. Now, I’m no expert, but since the real RAF Oakington in Cambridge was a fair distance away from Slough, I’d guess that we’re more likely to be looking at the entrance to say, RAF Northolt which was much, much closer to the studios.

Still totally bewildered, the policeman is promised a glowing recommendation when Father Unwin reports back to The Bishop. Quite a tongue-in-cheek joke for Unwin’s own benefit, but it does add this delightful air of mystery to the character of the Bishop, as if he somehow has great power over all of the nation’s public servants.

While Matthew braces himself for landing, Father Unwin drives onto the airfield and waits. This is our first look at the special effects unit’s miniature of Gabriel and, as one might have expected, it’s a beautiful little model. As if to mimic the live-action footage, however, it’s shot from quite far away.

Similarly, the model of the aircraft is kept teeny-tiny and far away from the camera as if the effects team were too shy to do anything particularly exciting with it. I guess the script doesn’t really call for a particularly dynamic or tense landing sequence despite the engine failures so the effects director for this particular episode, Bill Camp, probably decided not to go over the top.

An attempt is made to do something interesting with the scale of the various models by switching the tiny Britannia model for a larger one depending on its distance from the camera, but its nothing to write home about. Gabriel is driven around on the runway in the right-hand shot via a tiny slot in the set which was common practice for controlling models of ground vehicles on the special effect stage on the latter Supermarionation shows.

The Captain is forced to explain the concept of an emergency landing to the thick Ambassador who immediately suspects foul play. It’s okay though because the police are on the way to pick them up. I’m sure that’ll go smoothly.

Meanwhile, little Matthew gets to enjoy the indignity of falling the equivalent of several stories from the aircraft into Gabriel’s passenger seat. Okay, so just to recap, the Bishop gave instructions that “interception must not take place at London Airport,” so Matthew was tasked with forcing the plane to land elsewhere and here we are at Oakington… for some reason. I’m guessing the purpose behind using an abandoned airfield was to avoid any embarrassing diplomatic incidents and ham-fisted police busybodies getting in the way. But it’s never really made clear why such an elaborate scheme was needed when British Intelligence were very aware of who had the stolen computer and how they were going to get it out of the country.

Time for Father Unwin to punch a hole in this wasps nest.

Matthew is up for a fight but Unwin refuses to return him to normal size… which is slightly terrifying if you think about it too much. What if Unwin dropped the Minimiser in the font during a Christening and broke the darn thing while Matthew was mini-sized? Matthew’s taking quite a risk for BISHOP just by trusting that he’ll always be able to get back to normal size whenever he wants. Anyway, to demonstrate the Minimiser one more time, Father Unwin uses it to threaten the Ambassador because apparently that won’t cause a diplomatic incident.

Just like we saw with Matthew, the miniaturisation is shown from a very flat angle so that the effect can be achieved as simply as possible. It’s neat to have the other two characters in the background to demonstrate the size difference though.

Keith Alexander steals the show with the campest delivery he could have possibly managed of the line, “Your Excellency?!”

The negotiations are relatively swift and the mix of puppets looking big and small is really well-achieved. By filming the miniaturised character from far away, the wider shot and larger set successfully makes the Ambassador look teeny-tiny when cut together with shots of the same-sized puppets filmed close up to make them appear big and human-sized. Some of the veterans of Century 21 would likely have drawn upon their experience shooting Supercar‘s Calling Charlie Queen, the Fireball XL5 episode The Triads, and the Troy Tempest heat-induced nightmare edition of Stingray, Tom Thumb Tempest.

With the delicate and horrendously expensive minicomputer precariously dropped from a great height into Gabriel’s passenger seat, and without even checking the contents of the case, Father Unwin keeps his end of the bargain and returns the Ambassador to normal size. Now there’s a thought – if the Minimiser can turn tiny people back into normal people, can it also take normal people and turn them into giant people? Anyway, Father Unwin naffs off, with Matthew presumably hiding in the footwell.

Unfortunately, Constable Pushover turns up and just gives in to the Ambassador’s request to hand over the police car. After giving the computer away without a moment’s hesitation, the Ambassador decides that he needs to get it back. Apparently the economic prosperity of Dreisenberg is so important to him that he’s prepared to kill for it. Now there’s a government official who cares about people.

If you’re still invested in the location hunting, the Spitfire F.Mk 22 serving as a gate guardian at the main entrance pretty much confirms that this is RAF Northolt. In 1969, presumably not all that long after these shots were filmed, the Spitfire seen here was purchased for use in Guy Hamilton’s film, Battle of Britain.

Considering the mission a success, Matthew and Father Unwin take a moment to gush over the Minimiser, and reveal that it was invented by the late Professor Humbert, who frankly must have been some kind of sorcerer to come up with such a device. I like that there’s a hint of a backstory there but we don’t really need to get into the details.

But now there’s trouble. Matthew spots the Ambassador and his aide firing at them from the stolen police car. Silly diplomats. Now, if I attempt to identify every single road used for this chase sequence I will lose my tiny mind… but the distinctive trees make it clear that some of the shots were taken on Black Park Road, just a little ways away from the popular filming location, Black Park in Buckinghamshire.

Okay, maybe I am going to identify some more roads because my tiny mind is already a lost cause and that handy sign indicates the distance to Gerrards Cross, Wexham, and Slough, making this the village of Fulmer, specifically at the junction where Alderbourne Lane meets Fulmer Road. And yes, Thunderbirds fans, that’s Fulmer as in the Fulmer Finance Building from Terror In New York City. I’ll give the nerds on the front row a minute to dry their seats.

Matthew, still in his teeny-tiny state, pulls out his teeny-tiny gun and starts firing back at the police car. Call me a pessimist, but I don’t think that little peashooter is going to be of much help. The original script featured many more lines from Father Unwin about hating guns and detesting violence. These were presumably all cut because, well, it’s an Anderson show so if you’re not on board with some shooty shooty bang bang business you might as well pack your bags. So instead, he just advises Matthew to aim for the car’s tyres so that instead of getting shot, the diplomats will crash their car and possibly take out a few innocent pedestrians in the process.

The Ambassador and his aide discuss how wild it is that someone is firing back at them from the car in front that isn’t the driver. How they can even tell they’re being shot at by such a tiny gun I don’t know. At this point, I’ll remind you once again that these car chase scenes were originally intended to be shown during the pre-titles sequence to inject a bit of excitement into proceedings and provide a quirky narrative structure.

Okay, I may be good but I can’t guess a location just by staring at a field and some wooden fences. It’s Buckinghamshire for goodness sake, that’s as precise as I can manage.

Right, I genuinely just got extremely lucky with this one on Google Street View. While exploring the village of Fulmer, I discovered that this stretch of road is between Fulmer Place and Fulmer Grange House. I amaze myself.

Before I get too absorbed in this whole location hunt, I should probably comment on the fact that this is a very well put together chase sequence. Ken Turner and the location unit are obviously trying everything they can to make what was probably quite a slow chase to film appear energetic and exciting. The mix between live-action and puppets works quite nicely, and it’s fair to say the whole thing is a memorable climax to the episode. I’m glad we didn’t have to see it twice as the script specified though, as that probably would have taken the edge off it a little.

“Look out!” cries Matthew. Before we see what our little friend is screaming at, I’ve just remembered that Matthew left his high-tech suitcase back in the hangar at Heathrow. Hopefully one of the Bishop’s minions will pop over and pick that up before someone else finds it.

It’s a comic encounter with a tractor, not too dissimilar to a moment we’d see a few decades later in the New Captain Scarlet episode Instrument of Destruction Part 1 in 2005. I guess Gerry had a thing about tractors. Now, how many of you were fooled into thinking this shot was filmed on location? … yeah, me neither. Nothing about the lighting, set, sky backdrop, or camera angle matches the location footage and it causes this moment to feel terribly awkward. The poor effects team really were on the backfoot with this stuff.

Matthew dodges a bullet the size of his fist as the chase continues back on location. Again, not much of a chance of me identifying these generic country roads but we’re still in the general area between Slough, Wexham and Gerrards Cross.

Yeah you get ’em with that little toy of yours Matthew.

And just like that, Gabriel makes it home while the police car shoots past, never to be seen again. Did the Ambassador or his aide ever make it home to Dreisenberg? Or were they forced to settle down together and buy a lovely cottage in Fulmer? Trust me, after you’ve spent hours exploring it on Google Maps, you’ll never want to leave. A brief model shot shows Gabriel parking inside the garage which is a gorgeous little miniature set. Just look at the drain pipes and the windows and the roof tiles and the brickwork. It’s exquisitely detailed and I just wish it were possible for it to marry with the location footage better.

The next day, Matthew gets back to work in the garden while Mrs Appleby serves up boiled eggs with a side of gossip for breakfast. Clueless about Matthew’s real identity, she goes ahead and tells on him to Father Unwin about taking a day off. This is the first complaint in what turns out to be an on-going grudge that Mrs Appleby has against her young colleague. Quite what she dislikes about Matthew, I can’t say, but from the sounds of it Mrs Appleby has quite a vivid imagination.

Not every episode of The Secret Service ends with a sermon, but it feels appropriate for Father Unwin to have a moment for reflection after his first adventure with us. Among his congregation we have Captain Magenta, and in the row behind it’s Lady Penelope sporting the white coat she wore in the Thunderbirds episode, Alias Mr Hackenbacker. Then, in the reverse angle, we have a mini reunion for the cast of Joe 90 with Sam Loover, Mrs Harris, and Shane Weston all gathered to hear Father Unwin share a little more history about the Minimiser and Professor Humbert. We learn that he was an old friend who attended Unwin’s church services and has since passed on. The original script ends with the congregation actually singing the hymn All Creatures Great and Small with the word “small” emphasised just to really drive the message home. Needless to say, I think we all got the point without hearing Stanley Unwin sing at us.

And that, dear brethren, was A Case For The Bishop. I’ve found this review quite a fascinating process. Like many of the Anderson pilot episodes, A Case For The Bishop perfectly encapsulates everything you can expect from The Secret Service, but on this occasion I was forced to address the elements which, for me, don’t quite work rather than always singing its praises. I think the series improves from here, and it isn’t until the end of its run that I believe the true potential of the show’s unusual format is realised.

In short, I think the puppetry and most of the location footage is worthy of praise. It goes together about as well as you could expect. The special effects unit have some catching up to do, but hopefully that will be rectified once the scripts are tailored more towards things blowing up and some more advanced vehicles appearing here and there. The characters are top notch and very pleasant without being sickly sweet. The plot of A Case For The Bishop isn’t the best that the series has to offer but it’s not awful by any means. Overall, it’s a solid start to a wobbly series. Not all of the pain points will be ironed out but over the next few months but we will get to see the Century 21 team develop and get to trips with the challenging format they’ve been presented with. I’m keen to start looking at The Secret Service for what it is, now that we’ve addressed the main headlines surrounding its supposed cancellation and obscurity. Let’s just settle down, get cosy, and enjoy 13 entertaining half-hours of Sunday tea-time telly.

Next Time

References

Filmed In Supermarionation Stephen La Rivière

The Century 21 Script Book

Chris Bentley

The Case of B.I.S.H.O.P (FAB 80)

Mike Jones and Nick Williams

Century 21 FX Unseen Untold

Alan Shubrook

Timeline of Computer History

Computer History Museum

Stirling Road, Slough Trading Estate

Martin Kempton

Secret Locations

Mike Burrows

The Secret Service

A P Bird

Saying goodbye to the Old Control Tower

María Casero

Supermarine Spitfire MKXXII PK624

The Fighter Collection

FILM & TV LOCATIONS IN THE CHILTERNS AND THAMES VALLEY 1940 – 2014

Mark Jones

More from Security Hazard

Stingray – 1. Stingray (Pilot)

Oh yeah, I’m standing by for action alright. How’s about some serious high definition action courtesy of the 2022 release of Stingray on Blu-ray? I…

Keep readingThunderbirds – 1. Trapped In The Sky

For one time only we have the original Thunderbirds theme tune, which is heard in this episode and never again (aside from the TB65 episode,…

Keep readingCaptain Scarlet – The Mysterons

Directed by Desmond Saunders Teleplay by Gerry & Sylvia Anderson First Broadcast – 29th September 1967 This month, we are celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Captain…

Keep readingThe Secret Service © ITV PLC/ ITC Entertainment Ltd

I don’t like The Secret Service, it’s just so unremittingly dull and parochial (no pun intended), but this is a great article. And thankyou for acknowledging that the story Gerry always told about Lew Grade cancelling the show because of the Unwinese *has* to be nonsense.

I’ve long felt that Lew had realised within about 10 minutes that the show was a dud that just wasn’t going to sell. I’ll allow that the Unwinese scene may have been the point at which he stopped it and said “Enough!” (although I’m sceptical), but he was *always* going to cancel it.

If Grade had believed it was a solid saleable show apart from the Unwinese, he’d have instructed Gerry to rewrite and reshoot just those scenes. As you note, they’re very short and are never vital to the plot. The fact that he cancelled it completely indicates that he realised there were far bigger and more fundamental problems that were impossible to fix without starting from scratch.

I’m willing to bet that when Gerry pitched the show, he made it sound much more exciting, much more Anderson-like, and that Grade trusted him to deliver. I’m also willing to bet that Gerry’s story about the Unwinese being the beginning, middle and end of Grade’s problem was initially a way to avoid acknowledging his personal responsibility for all the many issues with the show, and later became something he’d said so many times, he’d probably convinced himself it was true.

LikeLike

Oh yes, another Supermarionation review series to look forward to each week, wonderful. Or should that be all wonderibold and excitiefololloping?

The Secret Service is indeed a really weird piece of television, but there’s a charm to it’s underdog reputation I find quite endearing. It never quite musters up a really outstanding instalment (besides the excellent finale), but one my initial watches the series grabbed me much more than Joe 90 (which I’ve come to appreciate more recently for its variety of format).