Picture an episode of Supercar about Mike Mercury and the team at Black Rock flying medical supplies to the heart of Africa, traversing mountains, desert, jungles, and hostile enemy airspace in the process. Doesn’t sound that out of the ordinary does it? It’s a textbook action-adventure plot for Supercar. Would it be a storyline particularly out of place in a later Supermarionation show such as Thunderbirds or Joe 90? Maybe its a little pedestrian for those shows and would need further development, but its not out of the question. Now, to get to the rather laboured point, what about The Secret Service?

Well, with the greatest respect to Father Unwin and Matthew… ain’t nobody asking those two to undertake a dangerous, globetrotting mission when, as far as we know, neither of them are pilots or have access to an aircraft. There’s been no indication that such a mission in the heart of Africa is even within the scope of BISHOP’s capabilities. So far, the series has been confined to overturning espionage plots in southern England.

So, what do you do if you’re Century 21, and you want to tell a story that wouldn’t be out of place in any other Supermarionation television series except for the one you happen to be making right now? That’s right, we’re heading for a dream episode! Seriously – in order to make a relatively run-of-the-mill action-adventure story work within the rather restrictive confines of The Secret Service‘s format, we have to enter a world of complete fantasy. Sure, this still produces the kind of quirky moments that feel in-keeping with the style of the series, but I really do think its remarkable that something so everyday and ordinary for the likes of the Supercar team is now the stuff of dreams for Father Unwin. That’s a startling indicator if one was needed that there is a massive gap between The Secret Service‘s format and what the Century 21 team had been comfortable with producing over so many years prior.

Errand of Mercy is, in my opinion, Century 21 trying to get back into their comfort zone of heroes flying around in exciting locales fighting foes and rescuing people, all in spite of the fundamentals of The Sercet Service not realistically permitting such exploits. The question is, now that the production team are put as far back into their comfort zone as it’s possible to go while still making something they can call The Secret Service, how well do they actually do at recapturing that classic Supermarionation spirit for far-flung, action-packed adventures? Let’s find out!

Original UK TX:

Sunday, November 9th 1969

5.30pm (ATV Midlands)

Directed by

Leo Eaton

Teleplay by

Tony Barwick

It’s worth noting straight from the off that this episode is very, very, very light on live-action footage. The vast majority of this episode is full of nothing but puppets and models outside of a few establishing shots and inserts. Hmmm, so we have a traditional Supermarionation story filmed using traditional Supermarionation production methods… it’s almost as if Century 21 had been making groundbreaking puppet films for the last 10 years and wanted to put their expertise to good use.

Anyway, Mrs Appleby is outside looking for Father Unwin but all we can hear is the sound of tinkering and clanging coming from Gabriel. Tony Barwick’s script also included an establishing shot of the church in the opening, then followed by the Vicarage establishing shot and a note: “We tell the audience they are adjacent by the sound of bell or a clock striking.” For some reason, Barwick felt it was necessary to make it very clear to everyone that the Vicarage is next to the church… except it isn’t… in real life they’re miles apart… but also, wouldn’t it be fairly obvious that the local priest lives in the general area of the nearest church?

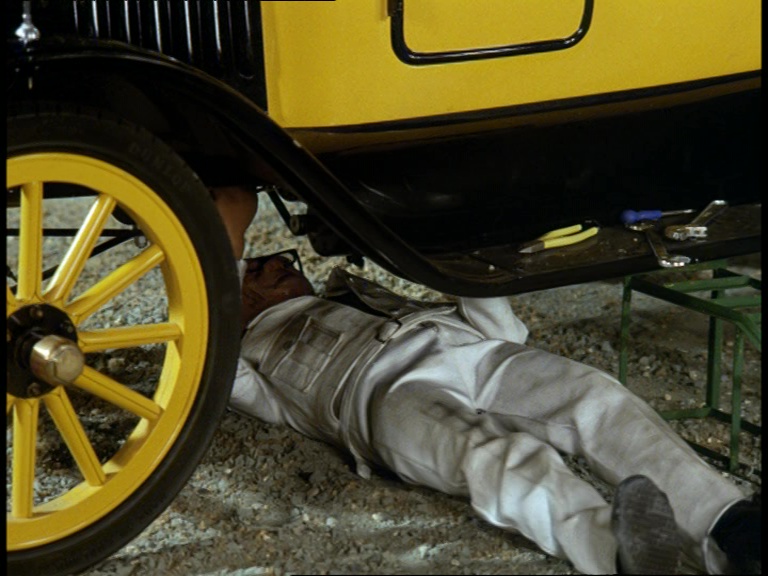

Unwin pops out from under the car because apparently Mrs Appleby has no peripheral vision. The little details of this scene really sell it with the mini set of tools, the oily but not too oily overalls, and the leg movements as Unwin tinkers away on the floor. The bond between Unwin and his car is explored to the max this week, having also been a sub-theme of every episode prior. The fact is that outside of him being a priest and a secret agent, pretty much everything else we know about the character of Father Unwin revolves around Gabriel – his love/hate relationship with speed, his general ignorance regarding technology, and his general sense of morality have all been dictated by the character’s interactions on the road.

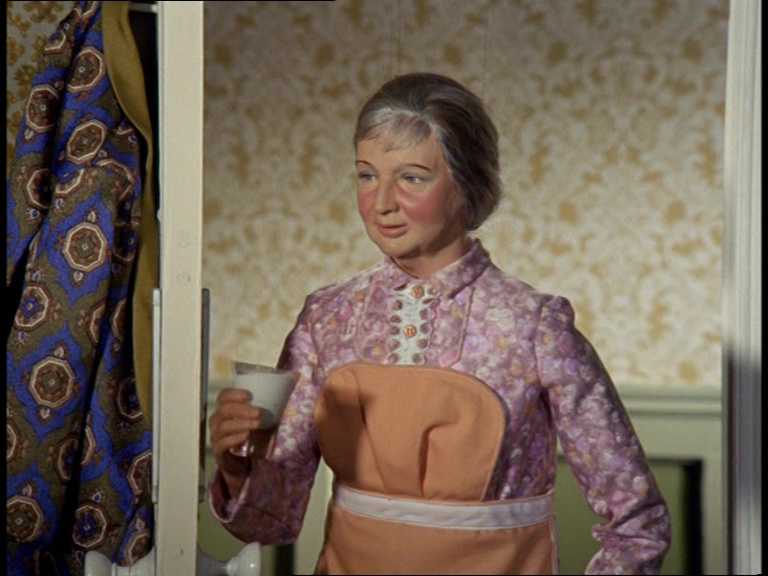

Mrs Appleby is in a fighting mood today and immediately suggests that Unwin gets himself a modern car… as if that would ever happen. We learn that she has a young nephew who drives her around in a fancy new set of wheels. This dialogue actually serves as a rare glimpse into Mrs Appleby’s life outside of her duties at the Vicarage. I can just picture her on a day off joyriding around the country roads of Buckinghamshire with that young nephew of hers, being driven to all of ‘er appointments like Lady Muck.

A heated debate ensues as Mrs Appleby readily lists of Gabriel’s faults – draughty, noisy, and hard to drive… exactly how she describes Mr Appleby too.

Unwin is determined to win the argument, romanticising the pleasures and struggles of owning such an old vehicle with great determination. It’s the most passionate he’s been when talking about anything for the entire series so far. There’s a sense in Stanley Unwin’s performance that he’s really latched on to the car-loving aspect of the character and knows how to deliver it with conviction.

The Supermarionation shows have, obviously, always had a strong connection with their vehicles, but we rarely explore the relationships between the lead characters and their machines. It’s understood that the Tracy boys probably like their Thunderbird craft, or that Stingray is the pride of the WASP fleet, but frankly we don’t often hear the characters talk that much about their own bonds with the vehicles. The closest we probably get is Virgil showing concern for Thunderbird 2 after it crashes in Terror In New York City, but the repair process is still very much described in purely mechanical, logstical terms. But even Joe 90‘s Jet Air Car, built by Professor McClaine himself, isn’t talked about by its creator with any warmth or affection – in fact he barely addresses it.

In The Secret Service, and this scene in particular, Father Unwin is really having to sell us on the appeal of Gabriel. As classic car owners often do, he talks about Gabriel like a person and makes the vehicle into a character with a quirky, changeable personality. Other Supermarionation vehicles aren’t really given personalities in the same way that Gabriel is. After all, the Thunderbird machines are all supposed to be the best vehicles of their kind. Fireball XL5 and Stingray are at the peak of space and underwater travel respectively. Supercar is toted as being able to do anything and go anywhere. They’re all perfect, and perfect characters don’t make for interesting telly, so they aren’t personified. Gabriel, flawed, out of place, and unusual as it is, becomes a true star of The Secret Service, and, in many ways, a symbol for the series itself.

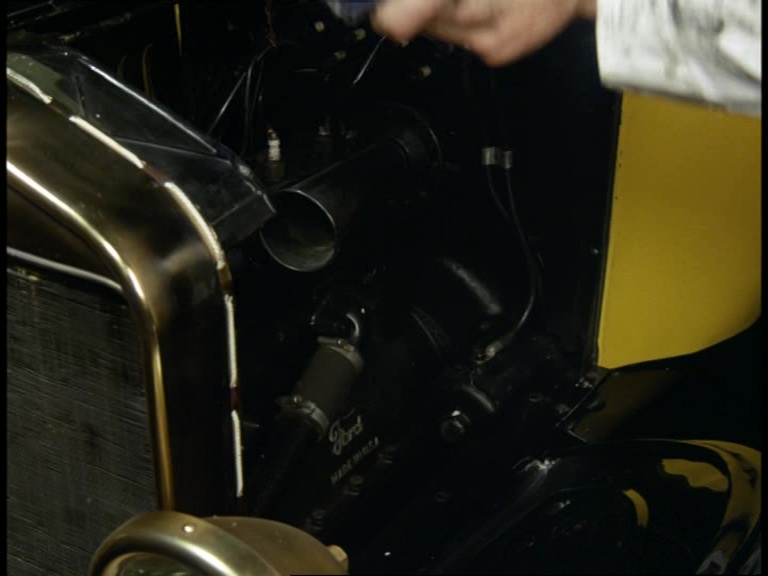

One of the few live-action shots filmed especially for this episode shows us the inner workings of the full-sized Gabriel. Father Unwin claims that it’s all original down to every nut and bolt. In real life that wasn’t actually the case. In Andersonic, Century 21’s projectionist and runner, Tony Stacey, described the purchase of the Model T for The Secret Service: “I went with John Read to Theydon Bois in Essex to buy the thing. I think we paid £1,200; it’d be about £25,000 now I should think!… Theydon Bois was a town in Epping Forest and this bloke restored classic cars. It was a little 2 seater Model T, 1917 or 18 model. It hadn’t got an electric starter and of course the crew soon started having problems with that so they actually modified it to have an electric starter which the later Model Ts did.” Since we don’t ever see Father Unwin get out and crank the engine by hand, we must assume that he was also taking advantage of an electric starter.

Father Unwin suddenly begins to feel faint and struggles to continue his grand speech about the lovely car. Mrs Appleby complains about him not wearing a hat to protect his bald patch from the sun. Blimey, attacking a man’s motor and his male pattern baldness in the same minute – Mrs Appleby isn’t afraid to kick the patriarchy where it hurts.

Father Unwin hits the ground like a sack of King James Bibles.

We are spared from the rather haunting image of Father Unwin passing out slumped over the bonnet of Gabriel as the script originally specified, and instead see him on the floor. Mrs Appleby calls out for Matthew’s help… assuming the young lad isn’t off galivanting with those harlots down at the garden centre again.

It’s certainly a different sort of cold open to the pre-titles scenes we’ve had in prior weeks – more of a slice of life than a big setup for the plot… then again, this week’s plot doesn’t really happen, so there isn’t much to set up.

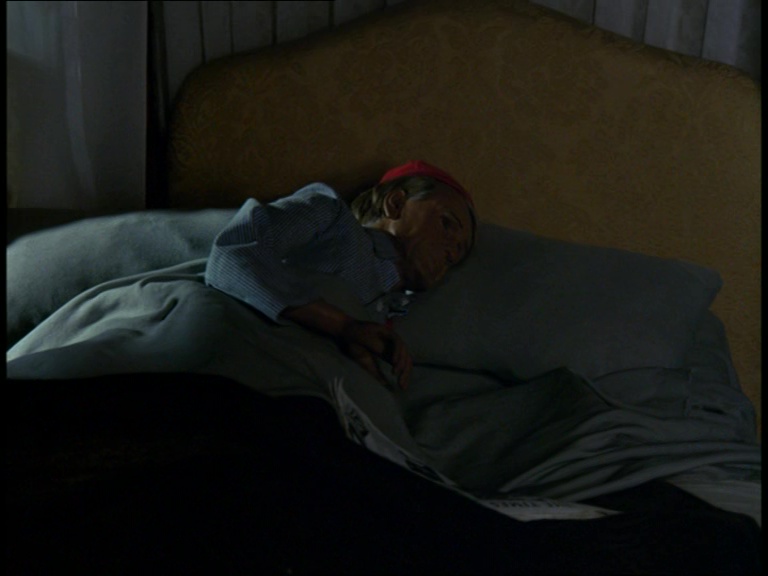

After the titles, we’ve fast-forwarded a few hours. For once, this nighttime shot actually looks like it might have been shot in something approximating darkness.

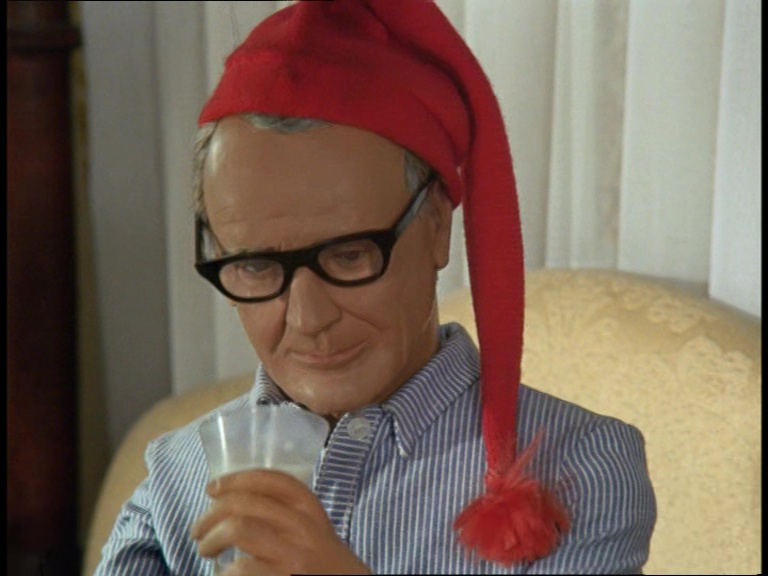

Father Unwin, restless as he so often is, sits up in bed with his newspaper when he should be asleep. Mrs Appleby, caringly overbearing as she so often is, brings in a cup of wallpaper paste and some pills to knock out the silly vicar. That’s a particularly ugly dressing gown hanging up on the back of the door. Note that Father Unwin is very clearly reading The Times… yes, I have more newspaper prop trivia coming up in a moment…

We learn that Father Unwin’s local GP is named Dr. Brogan… presumably the great-great-grandfather of Space Precinct‘s Lieutnenant Brogan – it’s worth highlighting that Tony Barwick worked with Gerry Anderson on devising and scripting the 1986 Space Police pilot film, so Brogan might have been a name he was particularly fond of, in the same way that his villains are always called Mason and the date in Captain Scarlet is always Barwick’s birthday, July 10th.

Unwin isn’t keen on taking his tablets and insists they be sent to Africa to help people in need. A blog such as this about old puppet TV shows probably isn’t the best place for discussing the sociopolitical complexities of foreign aid in the late 1960s, but since this episode has been good enough to raise the subject, I should at least provide some context. So, what was going on at the time that may have prompted Tony Barwick to write about the subject in the way that he did? Father Unwin makes his position quite clear – the people of Africa are in need of medical aid more than a priveleged country vicar in southern England. It’s a given but, y’know, not everyone might agree with that point of view so I thought it was worth highlighting.

The plight of postcolonial African nations struggling to thrive in a modern world of war, debt, and fiercely competitive trade had not gone unnoticed. In the 1960s, many in Britain and the rest of Europe were viewing foreign aid from the conservative perspective of pursuing commerical interests in order to boost economic development in the third world so that, ultimately, those nations could then contribute to the global economy and then, as a by-product, the people living there would thrive. There were just a few issues with that plan. The foreign aid money being offered to boost commercial ventures in Africa was going to the most powerful and corrupt individuals and not being passed along through fair wages to meet the basic needs of ordinary citizens… meaning that the former colonies were continuing to struggle despite all the money which was being sent to entirely the wrong people.

The debate by 1968, at least in Britain where the economic mood was turning from financial optimism towards a bleak recession, was focused on both the quantity and quality of foreign aid expenses. Since aid sent to Africa wasn’t yielding a satisfactory return on investment, there were some who believed it should be cut and reserved for Britain’s own interests. Meanwhile, others argued that aid spending should be increased and viewed on more compassionate grounds and invested in basic servies such as health, sanitation, education, and other essentials. This would boost the economic development of all people living in third world nations, rather than lining the pockets of commercial ventures alone. The Houses of Parliament debated whether the UK could and should offer aid that was directly proportional to their Gross National Product when such financial figures were hanging in the balance at the time…

Cut to Father Unwin reading his newspaper in bed, audibly fed up with such debates, and simply possessing the compassionate urge to redirect what he considers wasted resources over to fellow humans in need. Simultaneously wholesome, powerful, and challenging opinions to be expressed in a Sunday evening puppet series. It’s a sign that, arguably, Tony Barwick’s writing was outgrowing what viewers at home might have expected from the realms of Supermarionation.

So, to balance out the very grown-up approach to philanthropy and the good of humankind, Father Unwin is shown expressing disgust like a five-year-old child as he drinks down his pills and wallpaper paste. Mrs Appleby returns the favour by talking to the man like a five-year-old child being put to bed. Despite his protestations, Unwin can’t help but express his genuine thanks to Mrs Appleby, placing gratitude before his own pride – a very admirable character trait.

In close-up, Unwin’s copy of The Times has transformed into the Universal News and a return to that familiar newspaper prop which we last saw in To Catch A Spy with the headline changed. The advert for Lyons Restaurant remains prominent in the top left corner, as is the date Friday, Febrary 3rd, 1969… y’know I’m not sure heatstroke is even possible in the UK on a Friday afternoon in early February…

The “Plague in Central Africa” that the headline refers to could well have been a reference to the 1968 Influenza Pandemic which had a substantial impact upon public health in Africa compared to the rest of the world. The blockage of supplies could also refer to the events of the Nigerian civil war over the state of Biafra which was ongoing when The Secret Service was in production. The Nigerian government had captured the coastal city of Port Harcourt from the supposed rebels seeking Biafra’s independence, and imposed a blockade on food entering Biafra, leading to mass starvation in what became known in Western media as the “Biafran Genocide.” A million children starved in the rebel region while weapons were shipped in with ease from Britain to support the Nigerian army. A grave history indeed, and one that is at odds with the gentle, comedic notes that The Secret Service. I can’t hold that against Tony Barwick and Century 21 – they were just doing their job of entertaining the world – it’s simply worth remembering that context is always worth exploring when it comes to analysing works of fiction. Even something as quaint and easy to watch as The Secret Service can have the most surprising connections to real world events.

It’s midnight and we see the familiar grandfather clock in the hallway, as per A Case For The Bishop.

Father Unwin drifts off into Dreamsville with that familiar wibbly-wobbly effect…

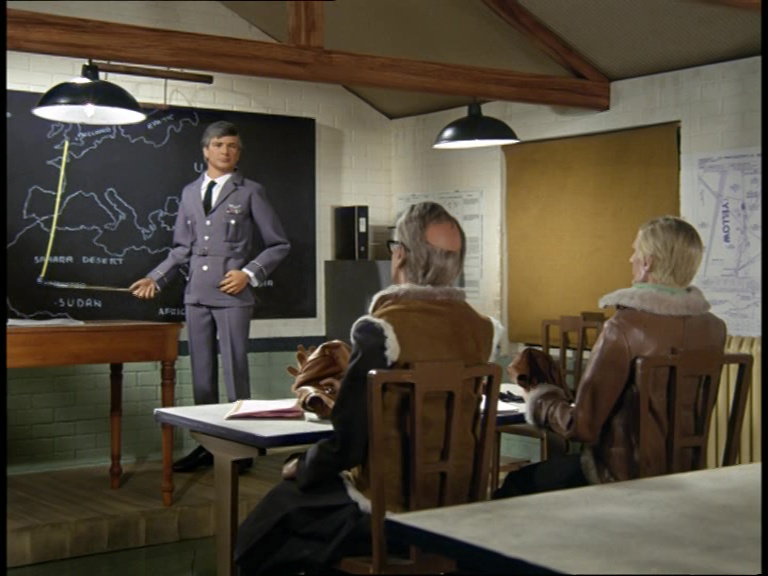

The model set of the airfield is suitably non-descript… probably because it isn’t described in the script at all. Just a smattering of buildings, lights, and a spinning radar dish.

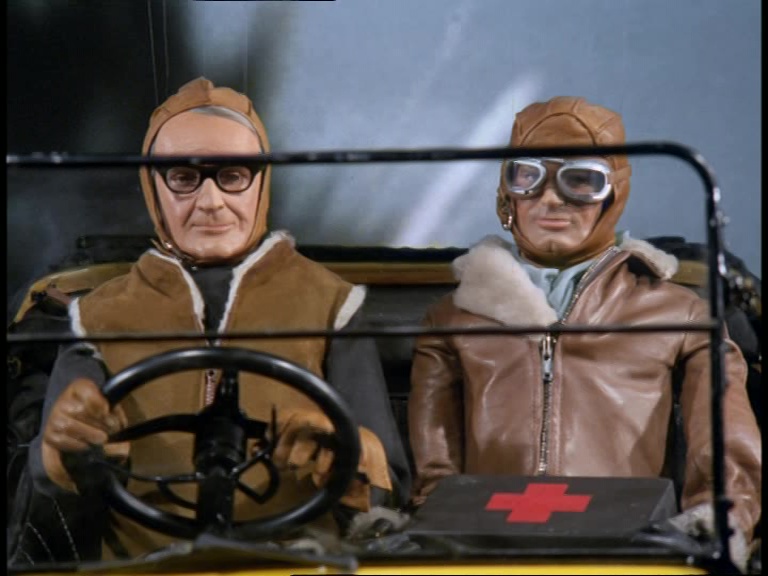

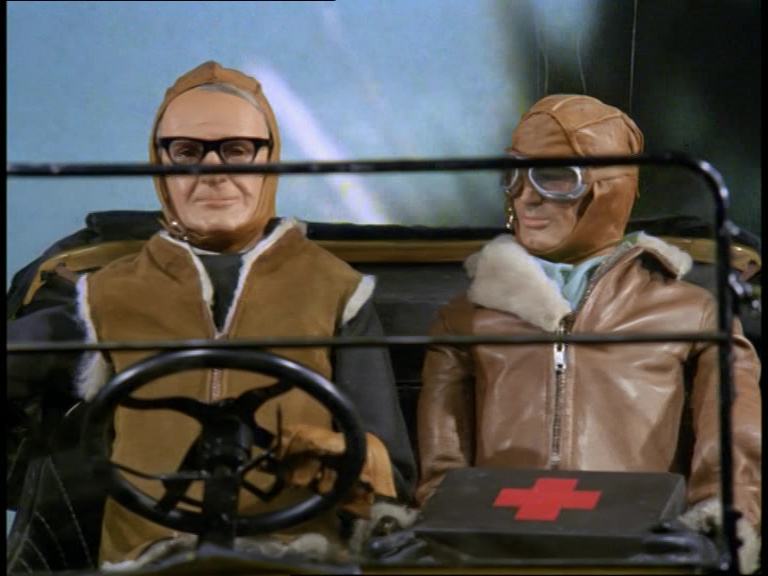

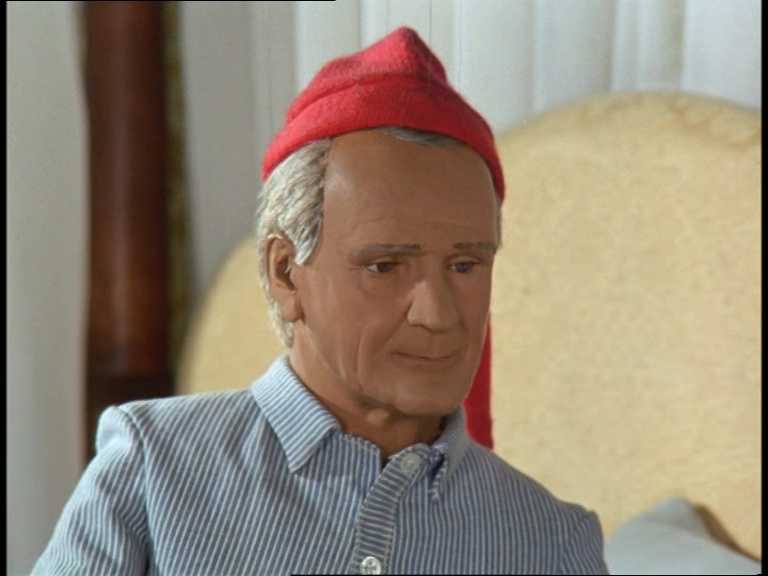

Father Unwin and the ever-faithful Matthew are dressed up and ready to fly, and listen keenly to their briefing from a man described in the script as a “FLYING OFFICER KITE TYPE” – a reference to a character from the radio comedy series Merry-Go-Round introduced by the BBC to entertain the troops during World War II.

The mission is explained as quickly as possible to set the scene and get the action underway. Unwin and Matthew are to fly south to Timbuktu in Mali (or Timbuctoo to use Tony Barwick’s more English spelling), and refuel in the desert before continuing to a jungle clearing to pick up the medical supplies, and then take them to Bishopsville and Doctor Purple.

Timbuktu is probably a familiar name to Westerners and is commonly used as shorthand in fiction for a mysterious, far-off land full of great wealth and learned individuals. Indeed, medieval accounts cite its position as a major intellectual hub in the Golden Age of Islam. Alas, from conquest in the 1500s, to European exploration and colonialism in the 1800s, to independence and major droughts in the 1960s, Timbuktu is now one of the most poverty-stricken and troubled cities in the world.

As for Bishopsville… well, unless a subtle reference is being made to the small South Carolina town of the same name, I think Bishopville is just a product of Father Unwin’s vivid imagination. As for Doctor Purple, I must admit that I think I’m missing a joke somewhere. There’s probably a reason for the colourful name but it’s a reference I’m not familiar with. Just call me a right thicky.

The script details, “A tremendous roar of jet engines. We do not see the plane but dust is swirled along the runway by the rush of air. (If this is possible)” – well I guess it wasn’t possible because the effects director for this week, Shaun Whittacker-Cook, has opted to simply zoom in on the control tower instead. The interior set is more or less the same one used for the airfield control tower seen in The Feathered Spies.

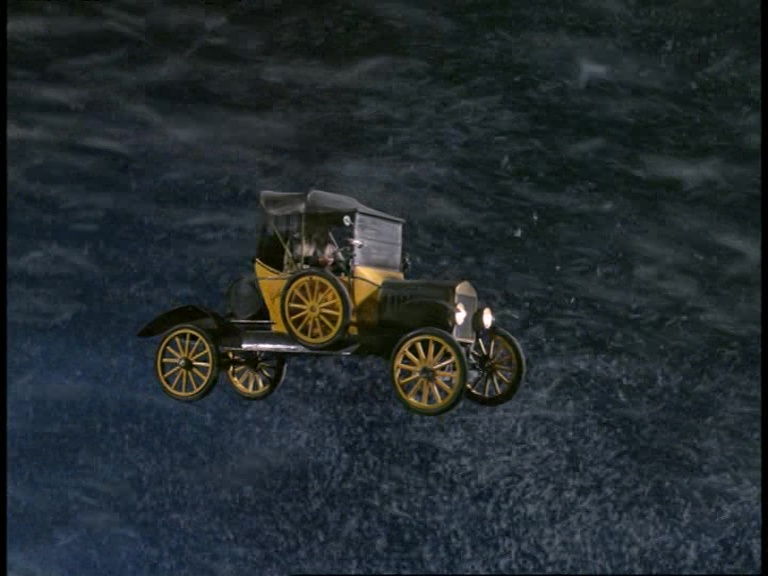

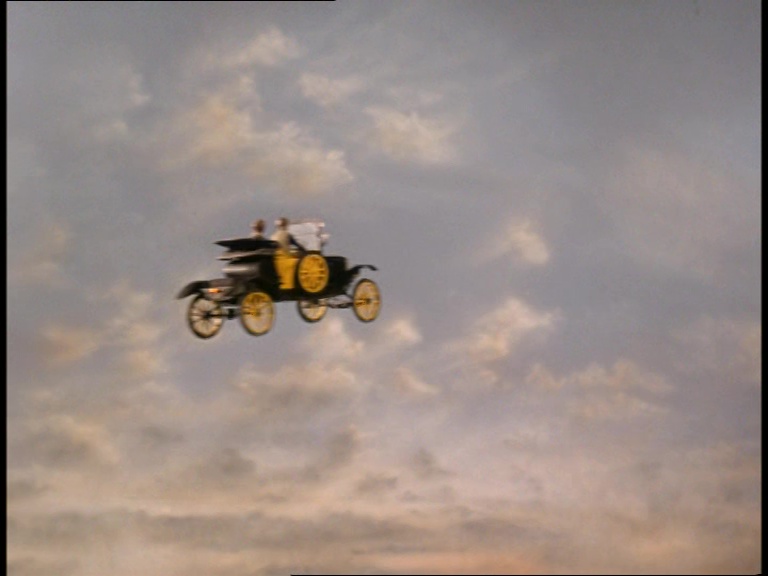

So, here’s the great gimmick for this week. In a sunstroke-and-sleeping-tablet-induced dream, Father Unwin is sticking to his belief that Gabriel could take him anywhere in the world and is now going to fly it to Africa and deliver the urgently needed medical supplies in the face of extreme peril. It’s a charming idea to essentially put Gabriel into the role previously occupied by the big Supermarionation star vehicles such as Supercar, Fireball, and Stingray but then play on the obvious differences to those earlier vehicles for comedy.

I dare say there was also an influence from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, the 1968 film based on Ian Fleming’s novel featuring Stanley Unwin in the cast, which premiered about two months after Errand of Mercy was filmed.

All that being said, comparing the script to the finished episode, I don’t think the director quite goes far enough to sell the surprising reveal that the Model T is being used in place of a supersonic jet. The sense of anticipation is there in heaps in Barwick’s descriptions but the actual shot of the car trundling onto the runway just looks a bit too ordinary… in fact it looks like every other bloomin’ special effects shot for the series so far – camera at the edge of the set, filming the model from as far away as possible with half the frame taken up by empty sky. It gets better though, don’t worry.

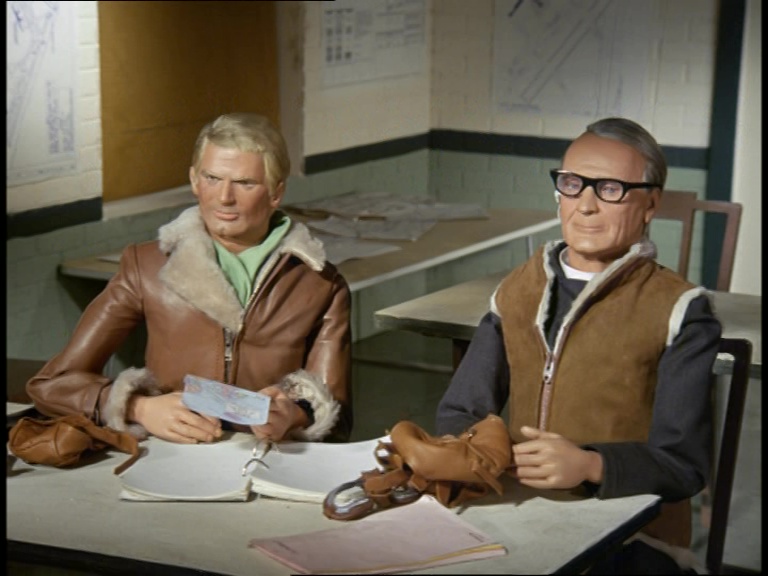

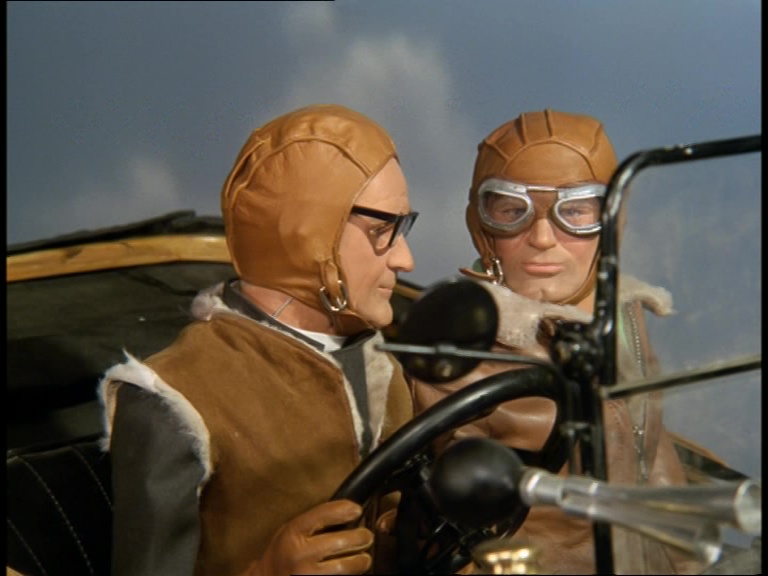

Don’t the lads look splendid though all dressed up for their adventure? I’m getting strong Biggles and Ginger vibes which just beautifully ties in with Father Unwin’s fondness for old-fashioned heroism and machinery.

The take-off is about as dramatic as it could have been I suppose. The flying Model T poses an unusual problem for the effects unit. Having spent the past decade learning to make their shots as realistic as possible, The Secret Service presented them with a format which demanded that their shots be absolutely identical to live-action footage of the same subjects… but didn’t necessarily give them the budget required to achieve this. Then, an episode comes along which asks them to make a totally unrealistic thing – a flying car – look both unrealistically dream-like, and realistically imposing and heroic… while also appearing comedically underwhelming and humble… while also retaining the overall contemprorary aesthetic of the rest of the series… my head is just spinning thinking about it.

Ultimately, without any moving parts, or a vapour trail, or anything else happening for that matter, the flying Model T looks exactly like what it is, a model swinging around on wires… and I don’t think there’s anything the effects team could have done to prevent that. Even with more dynamic and exciting shots, a flying car is never going to look like a fighter jet… and it isn’t supposed to… but it kinda needs to because that’s the joke… but it kinda shouldn’t because that’s also the joke. You see the trouble? The script is asking the scene to be two entirely different things at the same time. Fortunately, I doubt Shaun Whittacker-Cook or Leo Eaton had much time to think about such things and just filmed what was written on the page in the most competent manner they could.

Any kids at home re-create this sequence with their Dinky toy of Gabriel? Nope, me neither.

A short line from Matthew complaining about the draughtiness is cut from the dialogue but otherwise the final episode has stuck to the script pretty firmly so far. I enjoy the amusing formality and discipline which goes into Unwin and Matthew switching on the windscreen wipers – another lovely instance of Supermarionation poking fun at itself for all that routine “left-left two degrees” type of dialogue from previous series.

The blizzard blowing across the Alps looks absolutely fantastic. They don’t do snow too often, but when they do, the Century 21 team do it good. Having something else happening on screen helps the flying Model T to sit in the shot more comfortable. I’m more sold on the car flying over the landscape than I am watching it cross expanses of empty sky.

Continuing the theme of Father Unwin not being a particularly good driver we enjoy a brief moment of excitement as Matthew wets himself over nearly hitting a mountain. I will say that this is one instance of the special effects team doing a bit more than what the script asks of them, by having the car blast through the snowy peak, rather than just managing to pull up over the jagged rock as Tony Barwick originally suggested. It’s a great moment, and knits together perfectly with the puppet material too. I can fully sympathise with Matthew’s fears. He’s putting his life in the hands of someone who can’t even be trusted to boil his own eggs in the morning.

Father Unwin is rather more optimistic and does a rare bit of preaching when he asks Matthew to “trust in providence,” – as in to trust in God’s providence and believe that he will intervene and guide them. But frankly, Matthew’s navigation leaves a lot to be desired. They’re currently flying over the Alps in South Eastern France instead of taking the most obvious route to Timbuktu which is a straight line from England over Western France and down through Spain… about a 1000 kilometres away from their present position. Nice one guys.

A delightful change of scenery now as Gabriel flies over the Sahara desert towards the refueling station outside Timbuktu. Despite the bizarre detour though the Alps that it causes, I can understand why Barwick wanted this adventure to include snowy mountains, scorching desert, and steaming jungle. The variety of landscapes and the globetrotting aspect of the episode is a real highlight and something that the series has been lacking so far. The most memorable Supermarionation episodes are those that take our heroes to exotic locations in a slightly romanticised, swashbuckling manner.

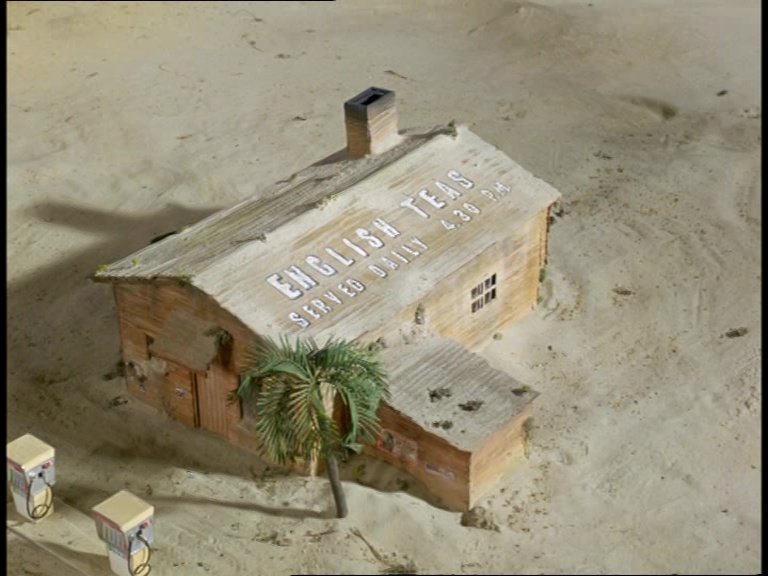

Speaking of colonialism, here’s an English Tearoom in the middle of the African desert.

Gabriel lands with the poise of a bumblebee carrying a tumble dryer, and drives around the back of the shop to meet the attendant who calls out with a familiar country accent…

Yes, in Father Unwin’s strange, strange mind, Mrs Appleby is living in the middle of the desert pumping petrol in a sunhat and serving tea. Alarmingly, the script originally suggested that Mrs Appleby should be “dressed as an Arab,” but good taste prevailed on this occasion. She does refer to Unwin as “Effendi,” the Arabic term for a man of high education or social standing.

Of course, Mrs Appleby invites the weary travellers inside for some tea. If we want to get picky again about the historical accuracy of Gabriel, it’s worth pointing out that the fuel tank on a 1917 Model T would have originally been mounted under the front seat, rather than at the back of the car as Mrs Appleby indicates here. Then again, Model Ts also can’t fly so I’m not sure I have a leg to stand on with that argument.

As they enter the tearoom/library of the Vicarage, the script suggested a poster be mounted on the door bluntly declaring “Welcome to Africa” before the quaint English sitting room is revealed. Needless to say, I don’t think they needed to be quite that on-the-nose about it.

Matthew grumbles in his faux country accent as Mrs Appleby fusses about the sand coming in. It’s not a direction in the script, so Gary Files might have taken it upon himself to keep up Matthew’s accent in front of Mrs Appleby, even though this is all a dream. It also just so happens to be the first time that the two characters have actually exchanged dialogue on-screen. They don’t normally address each other directly because… well, Mrs Appleby disapproves of him, Matthew probably can’t stand her, and – most importantly – those sorts of scenes are normally cut out of the scripts to keep the running time down.

The idea of all the action stopping so that Father Unwin can take a break and enjoy the comforts of home is quite in-keeping with the character, as is Matthew anxiously attempting to hurry things along. Unwin operates on the principle of “slow and steady wins the race” and stopping for tea is, in his mind at least, the sort of thing which nourishes him and therefore makes him more effective in the field. It’s a lesson he learned in the very first episode when he gets stopped for speeding, and ever since he’s always been an advocate for caution and thoughtfulness instead of rushing around.

The attitude is such an enormous diversion from the standard characteristics of a Supermarionation hero. The likes of Troy Tempest, Scott Tracy, and Captain Scarlet are men of action who throw themselves into danger without a moment’s hesitation. Matthew is keen to follow their example, but because Father Unwin is the star of the show, we ultimately have to take his direction and slow down with a more measured, conservative approach.

Optimistically, I would say that The Secret Service is taking a bold step towards presenting children with a different kind of hero who breaks the mold set out by Century 21’s earlier productions, and teaches a worthwhile lesson of more haste and less speed. Realistically though, Unwin’s slower-paced aversion to speed, danger, and violence ultimately resulted in a show which wasn’t well-received by the public or the people who worked on it. It could have succeeded in a different format, but the Supermarionation brand that had been building for ten years prior was so closely associated with action and adventure that the response to The Secret Service from audiences to this day is sheer bewilderment. It isn’t necessarily that the ingredients of the format for The Secret Service don’t go together that makes it an odd viewing experience – it’s the fact that the Father Unwin character actively resists embracing the fast-paced action that Supermarionation was invented for in the first place, and young audiences given the choice would rather take the action first and foremost.

That isn’t to say slower-paced children’s shows aren’t appealing and hugely successful. I’m speaking specifically about the Supermarionation worlds created by the Andersons from Four Feather Falls onwards. They rely on fast action and daring feats. Yes, Sheriff Tex Tucker might have enjoyed a charming sing-song, but he was also the fastest gun in the West and regularly raced around heroically to shoot at the bad guys… without stopping for tea and a boiled egg along the way.

Anyway! All that aside, it’s time for us to get back to the action as Gabriel takes off again.

Mrs Appleby is left behind while the boys go off on their adventure which is a feminist reading of the series begging to be expanded upon. She gets the last laugh mind you by calling Matthew bone idle… which he isn’t… yeah, I still don’t get why Mrs Appleby loathes Matthew so much. Sure, it’s an amusing dynamic, but putting some reasoning for the feud up on screen would probably help to sell it more for us at home.

So thrilling is this adventure that Father Unwin has time to comment on the nice weather… yes, he genuinely has a moment to talk about the weather. Don’t worry, the action will pick up a bit soon.

Teatime in the desert fades to nightfall in the jungle and suddenly all that quaint charm gives way to an uneasy sense of danger. The lavish and imposing jungle set which seems to stretch on forever into the darkness is a work of art.

Continuing in the spirit of looking slightly daft and out of place, Gabriel is parked in the middle of the clearing while Matthew and a very relaxed Father Unwin camp out. The dialogue has been tweaked slightly between the script and the finished episode, with Unwin originally describing it as “an eerie spot,” as opposed to the final line – “a rather pleasant spot.” The result of this change is that instead of Matthew simply agreeing with Unwin, it ends up falling to Matthew to come across as somewhat superstitious and untrusting of the surroundings. It’s a subtle difference but in a wider sense, the revised dialogue positions Unwin as a man of the world, comfortable wherever he goes, while Matthew becomes the wary and suspicious one finding danger in his own shadow.

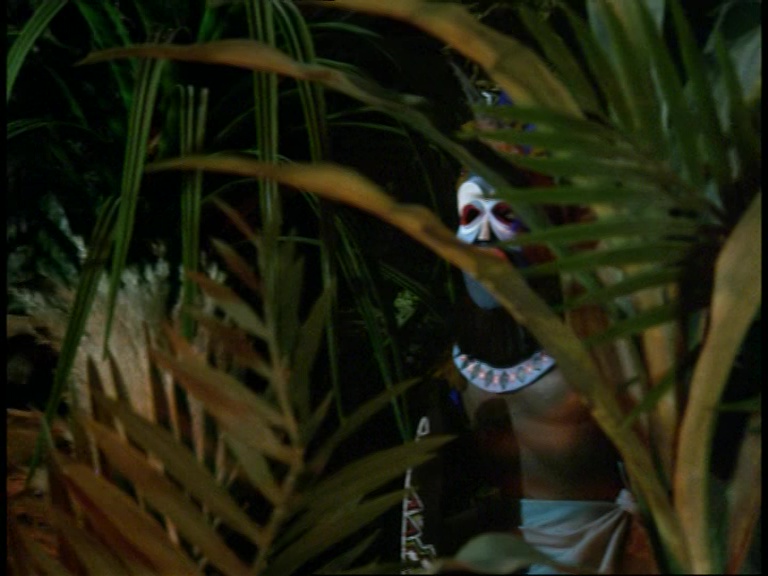

Then, it all kicks off. Multiple masked figures are shown in rapid succession, holding spears and the script describes them making a “HORRIBLE CALL“. The rapid cutting between shots is there to suggest that Unwin and Matthew are totally surrounded. However, it doesn’t take a genius to work out that they probably didn’t have enough puppets so Leo Eaton simply decided to shoot the same ones multiple times with minor alterations to the costumes. Speaking of costumes, the puppets are unusually rather exposed with only a few pieces of material covering their hinged joints, and specially sculpted torsos are on full display. The tribe of warriors holding spears and immediately being portrayed as a threat probably isn’t the most helpful stereotype in the world, but from Father Unwin’s perspective it’s likely representative of the world view he’s been brought up with.

A continuity error occurs when a spear has suddenly appeared sticking out of the ground in front of Father Unwin as he suggests staying calm. Then, a warrior is shown throwing his spear, but when we cut back to Unwin and Matthew only one spear is in the ground still. The error occured because the script originally specified that the first spear is thrown before Unwin says his line about saying calm, rather than after as he does in the finished episode. Presumably, the sequence was shuffled around in post-production.

Surrounded on all sides with no chance of escape, we fade to black for the commercial break. It’s certainly been a packed first half!

This beautiful model shot of the jungle clearing is lacking one important detail… the people who are supposed to be standing in the middle of it.

There they are! So, Matthew and Unwin have been tied up and now face the threat of fire and pointy things being waved in their general direction. Again, not a particularly sympathetic portrayal of an African tribe but we’re attributing it to Father Unwin’s subconscious so we have to say it’s probably not inaccurate to assume that this was the type of imagery that the Unwin would have heard about in works of fiction.

The vicar appears none too happy with the fire and pointy things getting quite close to his face. Wisely, he doesn’t panic and neither of the duo suggest resorting to violence. They just want to communicate. Barwick, unflattering in his portrayal of the tribe reduces their dialogue to the stage direction “NATIVE: (mumbo jumbo).” Unfotunately this leaves the all-white voice cast to shout and improvise their own ill-judged interpretations of an African language. Needless to say, things would be done differently now, and a modern production team might be more commited to cultural accuracy and sensitivity.

Just in case the native language hadn’t been belittled enough, we now come to a moment which I don’t find comfortable to watch. It turns out that the only language the warriors understand is Unwinese. Unfortunately, Unwinese equates to gobbledygook and comparing a tribal language to gobbledygook is not an implication that I agree with or think is a good thing for anyone to suggest. Now I’m not calling for this scene to be cut out or for Tony Barwick to lose his status as a well-regarded writer. (One note to point out is that much of the dialogue we hear during the scene itself isn’t present in the script and was likely improvised by the cast under Stanley Unwin’s direction.)

Now, I do think that Father Unwin meeting people who speak his own nonsense language is a fun conceit for getting out of a tricky situation, but indicating that African languages are comparable to literal nonsense is not the way to explore that idea. I do believe that this scene was intended as a piece of entertainment in a wider story whose ultimate aim was to do no harm. A choice was made by the writer which, at the time, probably wasn’t considered harmful. But between now and 1969 when this was first broadcast, an even greater number of people acknowledge that racism in any form does do harm. Therefore, when we see it in fiction, we should endeavour to understand its connection to real world places and people, and show some compassion when reviewing such material. It shouldn’t be destroyed or edited, but it should be understood that, like all media, it needs to be interpreted and viewed in context.

You will all make up your own minds, but you’re here for my viewpoint so I’ll give it to you, just as I would with any other scene. Based on my experience of watching The Secret Service, I believe that this joke was made at the expense of showing respect for a race of people, and I don’t think that is a fair or wise trade-off. I think Tony Barwick’s role was to get some Unwinese into the episode in a creative and comedic way (as it is in every episode) and I think there were better, funnier, and more ingenius ways to achieve that goal.

From a production standpoint, I think Leo Eaton and the puppet team have tried their best to ensure that even though the dialogue is insensitive, the visuals are reasonably sympathetic. The scenes feature beautifully detailed costumes and sets. The puppet heads and bodies of the African characters were specially produced or adapted with great attention to detail and an attempt at realism. Some of the puppet heads survive to this day and were part of the 1995 Phillips auction of items from Sylvia Anderson, Mary Turner and John Read’s collections.

With the medical supplies stashed aboard Gabriel, Father Unwin and Matthew depart with some more improvised Unwinese and cheering. The script specifies, “Refer Stanley at reading,” when other members of the cast who aren’t Stanley Unwin are called upon to speak Unwinese.

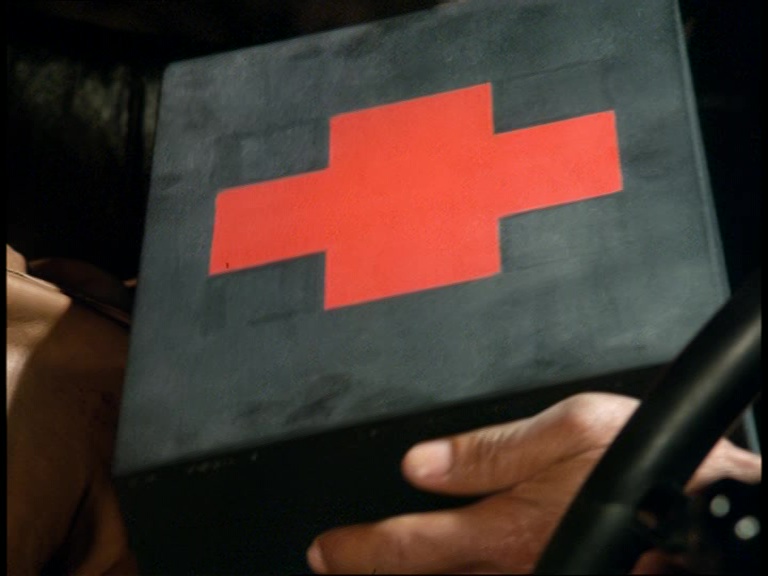

One thing that’s glossed over is exactly why the tribe had a perfectly prepared box of medical supplies in the first place. I know it’s a dream, but couldn’t Matthew and Unwin have brought along a much larger supply of medicine straight from England and flown to Bishopsville directly? Probably would have made the episode quite a bit shorter…

Here are some absolutely gorgeous shots of the sun rising in the sky. In fact, this episode has a lot of really beautiful sky backdrops. Bizarrely, Tony Barwick’s script describes that, “A disc is pulled up over a long shot of the jungle. On it is written “SUN” and the scene is lit.” That’s a very visual, very meta joke, worthy of Dick Spanner P.I. and definitely wouldn’t have fitted the overall tone of The Secret Service, even in a dream sequence. It’s fascinating that Barwick was prepared to go so out-there with his gags even this far back in his career before the anarchy of Terrahawks, and equally fascinating that the effects team were having none of it and countered it with one of the most realistic sun shots they’d ever produced.

I have to say that some of these effects shots are top notch. The Model T swooping in low over the trees is really good and quite exciting. The same drum track heard in the Stingray episode, In Search of the Tajmanon, is played to build a sense of dread.

It isn’t quite conveyed on screen, but the drums are supposed to be passing along a message of impending danger through the jungle from one drummer to another. That’s what Unwin means when he describes it as a primitive form of radar.

Gabriel gains altitude and the gorgeous shots of the jungle continue to impress me. The Century 21 team were clearly enjoying the challenge of producing all these exotic locations after so many weeks of very English settings and situations to work with.

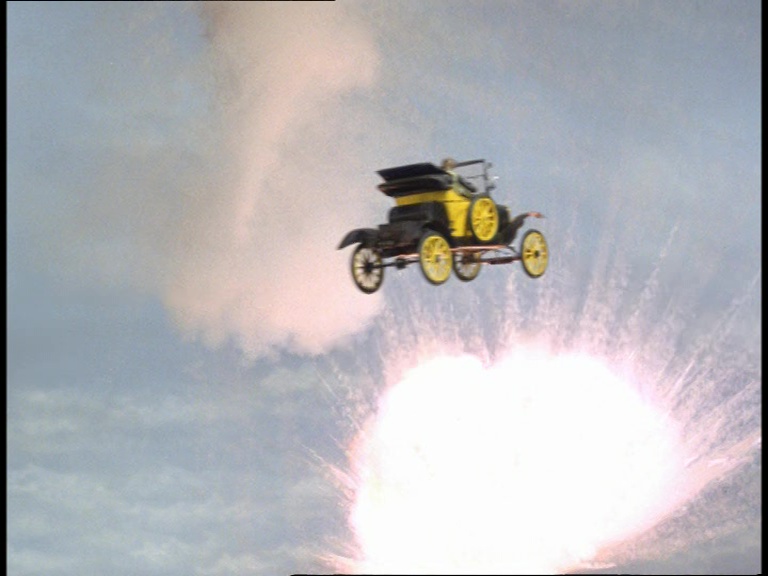

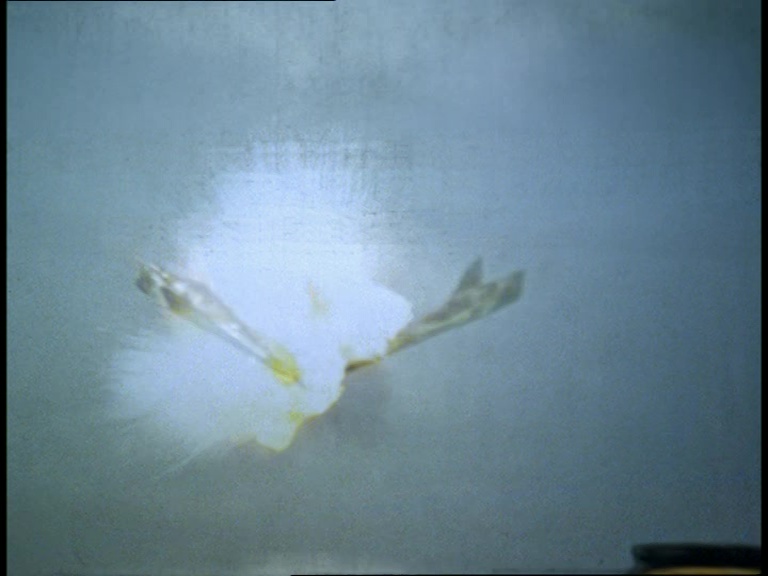

An airfield in the middle of the jungle, armed with the latest jets and anti-aircraft guns, unleashes absolute carnage. The explosions pack a terrific punch as the cannons unload shells which narrowly miss Gabriel every time. I can almost hear the cheers of the effects team with every bang and blast.

Back projection makes a rare appearance here. It was a technique used frequently on the set of Supercar but then cut back dramatically in the later Supermarionation productions in favour of rolling sky backdrops and model sets. I guess setting off large explosions on the puppet set itself while also simulating Gabriel in flight would have been too difficult… as much as I’m sure Shaun Whittacker-Cook wanted to give it a try.

The barrage continues as Father Unwin pushes Gabriel to the limits while making quips about the paintwork getting scratched… yeah not every gag can be terribly original.

The risky flying pays off when a cannon opens fire too close to the ground and ends up blowing up part of the base. Oops, butterfingers!

In the burning remains of his office, a vaguely Germanic military General is not amused by the monumental miscalculation. It’s a gorgeous touch of humour in amongst an episode which, it has to be said, has been rather hit and miss with its comedy so far.

Unwin asserts that it isn’t over yet – a crushing disappointment for ATV Midlands viewers waiting to watch the News From ITN which was on next.

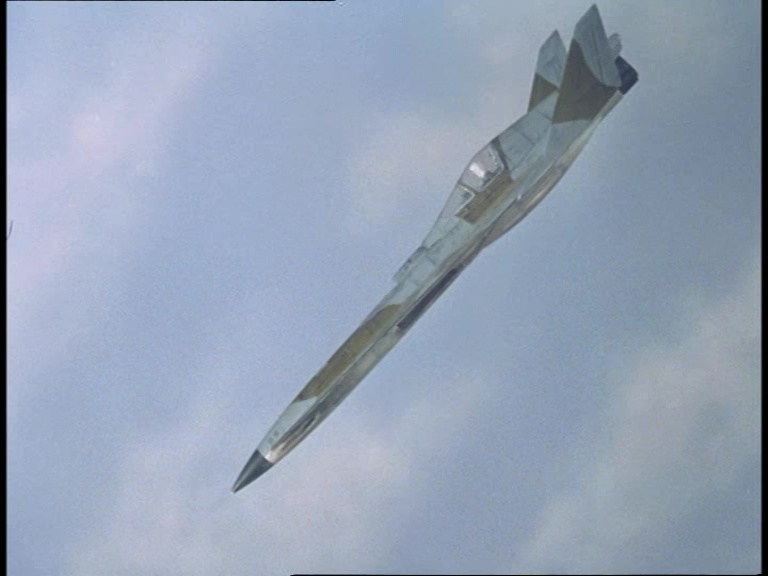

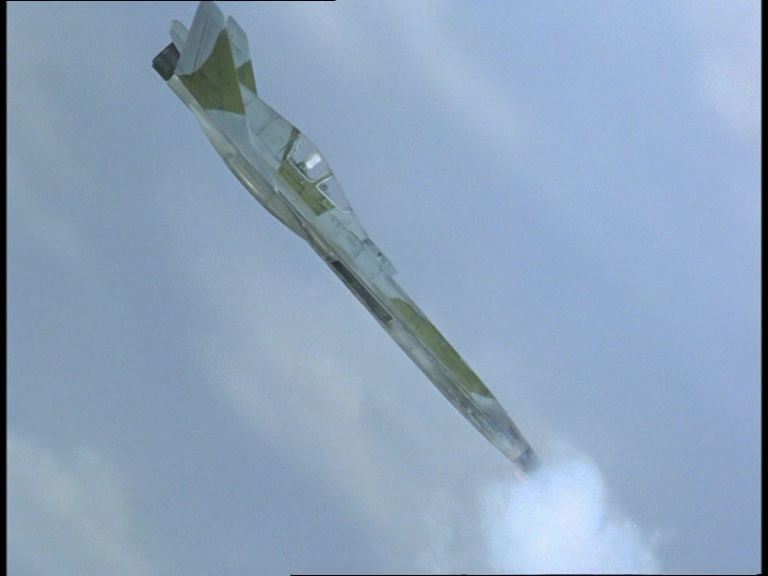

The aircraft we saw earlier scramble in formation to go after Gabriel. It’s a dream sequence so we can forgive any anachronisms, and the effects team therefore allow themselves to produce some lovely, futuristic jet models with unusual rear-mounted cockpits. One of the filming miniatures survives to this day and was sold through The Prop Gallery recently with the following description:

“Constructed from wood the miniature is meticulously hand painted with camouflage detailing, panel lining and multi coloured emblem, the underside is again highly detailed and hand weathered. The miniature still retains the metal tubing to the underside which was used to suspend it on wires for filming… The jet measures approximately 12″ long and remains in good screen used condition.”

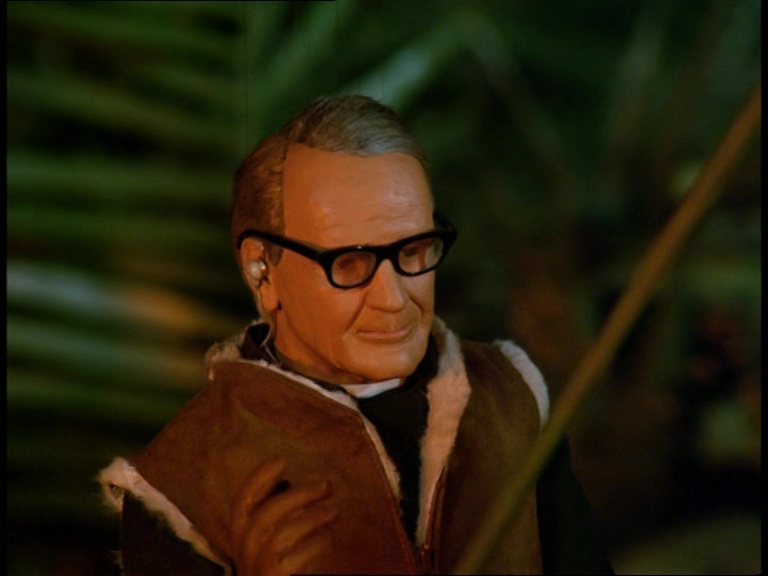

Meanwhile, the puppet set makes use of the Angel Interceptor cockpit first built for Captain Scarlet but also seen throughout Joe 90 repurposed in various guises. This set required the use of an under-control puppet since the aircraft’s canopy prevented the use of overhead wires. Let’s get a closer look at the puppet to see if we can recognise them…

Heavily disguised under a flight helmet and oxygen mask, I’m fairly sure that’s Spectrum’s second favourite person, the loveable Captain Blue from Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons. Like his co-star, Captain Scarlet, Blue was kept out of the limelight during the production of Joe 90, but was then brought back into service to play a part in The Secret Service. We’ll be seeing him again in more prominent roles later in the series.

The humour keeps on coming as the crispy General learns what they’re up against. The scripted line “Gog in Heidelberg” is transformed it into something even more nonsensical just in case you weren’t done with the whole “don’t-foreigners-sound-funny” gag. But the dramatic overacting which Keith Alexander and Jeremy Wilkin deliver is genuinely hilarious. They totally commit to the farce with their tongues firmly in their cheeks and oh boy there’s more to come.

Let battle commence! Father Unwin and Matthew spot the jets on the port side via the back projection screen. Our fearless pilot has confidence in his flying machine and I must say, Unwin’s saintly optimism is beginning to annoy me. Not a lot. Just enough to produce excess stomach acid.

All the swooping and diving and bangs and roars of jets and missiles and car engines is fantastic. Some of the footage shown behind the puppet set on the back projection screen doesn’t quite hit home, but I imagine on a 1969 television set it sufficed perfectly.

Now, the cynical hooligans among you might think that to save time and money the same shot of the first pilot has been flipped to create a shot of the second pilot… congratulations, you’re learning. The jets collide and explode on the back projection screen while the puppet-sized Gabriel ducks out of shot. Like I said, it doesn’t pack quite so much of a punch because it’s a fuzzy projection, but I’m honestly enjoying this silly action sequence too much to care.

Ugh, Father Unwin is so holier than thou that when a fighter jet has orders from Burnt Face Man to literally murder him he gives an erroneous hand signal and then apologises afterwards. What a smug twerp. (Also, how’s Burnt Face Man for an early 2000s internet reference?)

But things get really tense when Gabriel is chased down by the fighter jet in a speedy race to the ground. Matthew, utter whimp that he apparently is this week, believes that pulling out of the dive is impossible. He’s probably just grateful that he won’t be buried in his ruddy suitcase. Speaking of which, the plot carefully dodges any need for the Minimiser this week, and that seems odd considering it’s kind of what the whole series is supposed to revolve around.

Gabriel pulls out…

The other guy, not so much.

Captain Smugwash hopes the pilot isn’t seriously injured. Really? Did… did you see that explosion? Are you… are you living in a dreamland? Wait… don’t answer that…

Yes, because it’s a comedy dream sequence, the Mercenary Leader hasn’t been barbecued alive but has instead taken up residence in a tree while some kind of lively jungle creature can be heard laughing at him.

General Charred-Beard mourns the loss of his squandron while a particularly sad tune creeps into the soundtrack from Barry Gray’s archive which I believe dates all the way back to Four Feather Falls – a rare opportunity to hear a cue recorded for that charming little Western series in another Supermarionation production.

Gabriel has landed safely outside a cave which is apparently their final destination, Bishopsville. I’ll be honest, I don’t think there are gonna be many people in need of medical supplies living in there.

Suddenly, things turn into the final episode of The Prisoner and we’re inside the cave looking at some very modern doors. Beyond them, it’s the bloomin’ Bishop’s office. Yes, Doctor Purple is none other than the Bishop looking absolutely dashing in a purple tie and white linen suit. It’s a much more appropriate costume than the “headdress of purple feathers like an Indian Chief” that the script suggested he should wear.

Matthew and Father Unwin confess to being a bit tired after their arduous journey to bring a tiny box of medicine to a doctor who isn’t a doctor at all but a man in a luxurious office without a care in the world.

Just to wrap the dream up with a little bit more weirdness, the Bishop directs the two travellers towards the secret passageway which looks suspciously like a black void of nothingness and doom…

It’s an Anderson dream sequence so it naturally ends with someone spinning and falling and spinning and falling some more. Just a few months before this episode was broadcast, Patrick Troughton’s Doctor Who had departed British television screens in a similiar manner at the end of The War Games. That’s not really relevant to any of this, I’m just sure I can’t be the only person who thought of that.

Wibble, wibble, wibble – Father Unwin wakes up with Matthew in his room and a desire to drive to Hampstead Heath. Yes, blow me, it was all a dream. Every Supermarionation series (if we count Thunderbirds Are Go (1966) as a part of Thunderbirds) has at least one mad moment which takes place in the land of make-believe inside the disturbed subconscious of a protagonist’s mind. Sometimes, it’s disappointing when it turns out to be a dream that never really happened. Sometimes, we’re glad none of that weirdness can happen in the show proper. This time around, I don’t know how the heck I feel. We’ll unpack that in a moment.

For the first time since A Case For The Bishop the episode ends with a quick sermon from Father Unwin basically telling everyone to look after those less fortunate than ourselves. Several scripts so far have suggested ending with a sermon but cut it, so it’s odd that Tony Barwick not only returned to that framing device for this episode, but also that this scene doesn’t actually feature in the original script. The episode was supposed to end with Gabriel cheerfully driving down the road bound for Hampstead Heath. For some reason, the decision was taken to end on a more poignant, spiritual note, recapping Unwin’s selfless devotion to a life of service… secret or otherwise.

As I expressed at the top of the article, Errand of Mercy feels to me like Century 21 aching to get back to its heroic, action-adventure, science fantasy roots without the restraints of live-action footage shot in leafy Buckinghamshire, or a central character who insists on doddering around in a bright yellow antique car. The trouble is, they simply couldn’t get rid of Father Unwin or Gabriel for a week. Therefore, the swashbuckling story has to be molded around a character who isn’t terribly well-suited to an action-packed environment full of violence, quick-thinking, and serious, life-threatening acts of heroism. Tony Barwick, successfully puts character first and tries to use Unwin’s moral compass to drive the plot forward. That’s how good television should be written, but it does mean that the world of action and adventure has to bend around the character’s heart of gold to keep going. That’s why Errand of Mercy has to unfold in a dream.

In the real world of The Secret Service, the character of Father Unwin simply wouldn’t be able to fly into a warzone and deliver supplies. He’s too slow, too naive, and frankly too much of a goody two-shoes for me to put up with. If Unwin was doing what the likes of Mike Mercury, Steve Zodiac, and Troy Tempest did every week, I’d want to slap him in the face for being so sanctimonious and optimistic all the time. Those earlier Supermarionation characters had a rough-and-tumble love of danger, some and razor-sharp and down-to-earth wit to make them bearable and… dare I say it… a bit of sexiness. Unwin has none of that. Fortunately, Matthew has at least a little bit of that, so usually he gets trusted with most of the action while Father Unwin waits outside or does something less taxing. This week, it took a total fantasy to try and get Unwin, the central character, into an action-oriented role… and that to me indicates that maybe the format is a little bit… wonky. So is it good or bad that the whole thing turned out to be a dream? I say good, but only because there really wasn’t another way for us to get an adventure quite like it… that is until the writers gained a firmer grasp on how to make the series tick later on down the line.

I’ve said my piece about some of the more questionable cultural inferences made in this episode so we won’t dwell upon that, but otherwise I will say that this is an entertaining yarn that’s stacked full of enjoyable moments. The dogfight at the climax of the episode is a real highlight and an example of the great things the special effects team were still capable of creating when given a story which opened up their toy box, rather than forced them to work in the real, grown-up world…

Next Time

References

Filmed In Supermarionation Stephen La Rivière

OVERSEAS AID (UK Parliament Hansard 29 May 1968 and 28 November 1969)

The history of foreign aid

Keri Phillips

Remembering Nigeria’s Biafra war that many prefer to forget

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani

Biafra Genocide – A Forgotten History

JB Shreve

How Timbuktu Flourished During the Golden Age of Islam

Kai Mora

More from Security Hazard

Stingray – 28. In Search of the Tajmanon

I wouldn’t call myself a particularly scholarly author. I’m more suited to sniggering when a puppet goes cross-eyed or pointing out when a prop gets…

Keep readingThunderbirds – 5. The Uninvited

If you like sand, this is the Thunderbirds episode for you. There’s tons of it.

Keep readingCaptain Scarlet – Attack On Cloudbase

Directed by Ken Turner Teleplay by Tony Barwick First Broadcast – 5th May 1968 There is one thing that Supermarionation series are notoriously bad at…

Keep readingThe Secret Service © ITV PLC/ ITC Entertainment Ltd

Every part of this episode is great for me, I definitely think it has that Chitty Chitty Bang Bang feel to it and there is a nice mix of humour and suspense in it.

A real favourite episode of mine and a great laugh.

LikeLike

Errand of Mercy was actually the episode that first introduced me to The Secret Service’s existence way back in the day (around 2010 or so). There was an regular column in SFX magazine where a small panel of writers would review random episodes of archive Sci-Fi or Fantasy tv shows, and one month The Secret Service was on the offering. It was the first time I’d ever heard of another Supermarionation show beyond Joe 90, and sounded absolutely baffling.

Back in 2017 I first sat down to watch all the colour Supermarionation series, having only really known Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet before then. The Secret Service was probably the biggest revelation of the bunch, as I found it quite charming despite the oddities in tone and plotting. It was strangely put together, but had its heart in the right place, and for that reason I could never dislike it despite the flaws in the premise. So thanks, Errand of Mercy, for bringing my attention to the show in a second-hand way.

LikeLike

My least favourite episode of the series (I don’t care for any of the dream episodes in Supermarionation to be honest – all very OTT for me). Almost skipped it in recent reviewing but watched it last and would agree it is the most Supermarionationish episode of the series and the least Secret Servicish. I liked the comparator to Supercar which really gives a sense of how far the team had come.

For one comment you made Jack I think I might have an answer.

The Bishop in the dream is known as Doctor Purple.

You said: “I think I’m missing a joke somewhere. There’s probably a reason for the colourful name but it’s a reference I’m not familiar with.”

Though I’m Catholic myself, I know from some limited experience that Anglican Bishops wear Purple shirts and cassocks as their colour of office and rank. To confirm this I googled it: “Q. What colour do Church of England bishops wear? – A. During the 20th century, Anglican bishops began wearing purple (officially violet) shirts as a sign of their office.” So the name Doctor Purple is a subtle joke to the colour that Bishop’s wear. Be glad that Father Unwin is not a Catholic Priest working for C.A.R.D.I.N.A.L because they wear scarlet for which Doctor Scarlet might have been very confusing for the Supermarionation !

Hope this is helpful and of interest.

Really enjoy the blog.

LikeLike

Paul Metcalfe’s dressing gown in ‘Model Spy’?

LikeLike

Sorry to bother about the comment, that was not Captain Blue portrayed as the pilot. That was Lieutenant Dean’s puppet.

LikeLike