First US Broadcast: Tuesday, December 9, 1975 on NBC.

First UK Broadcast: Saturday, December 11, 1976 on BBC1.

Written by

Johnny Byrne

Directed by

Charles Crichton

Produced by

Gerry Anderson

Appreciating the timeline surrounding The Day After Tomorrow: Into Infinity and its inherent ties with Space: 1999 all makes for some interesting food for thought. The first season of Space: 1999 was shot between November 1973 and February 1975. It was a long and expensive shoot, the fruits of which would not be screened until September 1975. ITC more desperately than ever wanted to make its money back from a US network sale. The fate of the series, and seemingly Gerry’s future prospects would be measured on its American reception. Always looking forward and keen to improve, Anderson already knew that some changes to Space: 1999‘s format were needed for the second season even before the first had been transmitted. He requested that script writer Johnny Byrne conduct an analysis of the first season to find its strengths and weaknesses.

While awaiting Space: 1999’s television premiere, Anderson received a commission from NBC vice-president of children’s programming, George Heinemann, to contribute a film to the NBC Special Treat educational anthology series. The subject of this film was pre-determined as Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. The Day After Tomorrow, started shooting in July 1975 while Anderson and Byrne were likely considering paths to take with Space: 1999‘s second season, and before viewers had seen the first.

Production on Space: 1999 was slated to resume for a second season in Autumn 1975, but this was far from being a done deal since the American market’s response was so critical. Nobody was prepared for quite how dramatically plans for the second season would change when undesirable ratings in America eventually materialised in the Autumn of 1975. The series was cancelled, then recommissioned again with a delayed start date of January 1976, on the basis that the infamous Fred Freiberger start from scratch on the show’s format. Anderson appointed him as producer and, well, you might know the rest.

The Day After Tomorrow happened before armageddon was unleashed and Space: 1999 went the way it did. The fact that NBC even approached Anderson demonstrates that in some respect, the industry still trusted Gerry to produce “the right stuff” for the young American audience. Maybe The Day After Tomorrow: Into Infinity was the ticket Anderson needed to produce a lucrative series for American television without the increasing difficulties and seeming lack of confidence presented by ITC.

With that context in place, we can perhaps view The Day After Tomorrow as a presentation of what might have been. Imagine if Gerry Anderson and Johnny Byrne had been allowed to make the adjustments that they felt were necessary for Space: 1999‘s second season… rather than getting flattened under the Freiberger bulldozer and ludicrous input of ITC’s New York office. Ultimately, I’m of the opinion that the second season of Space: 1999 was an expensive mess made to look cheap. It left Gerry’s career on a knife-edge. The final product is weighed down by heavy production issues and a strained atmosphere caused by the format being vastly at odds with what America apparently wanted. Watching some episodes feels like wading through thick, lumpy, buckets of cold bovril.

By comparison The Day After Tomorrow feels dignified, effortless, light, hopeful, and demonstrates profoundly why less is so often more.

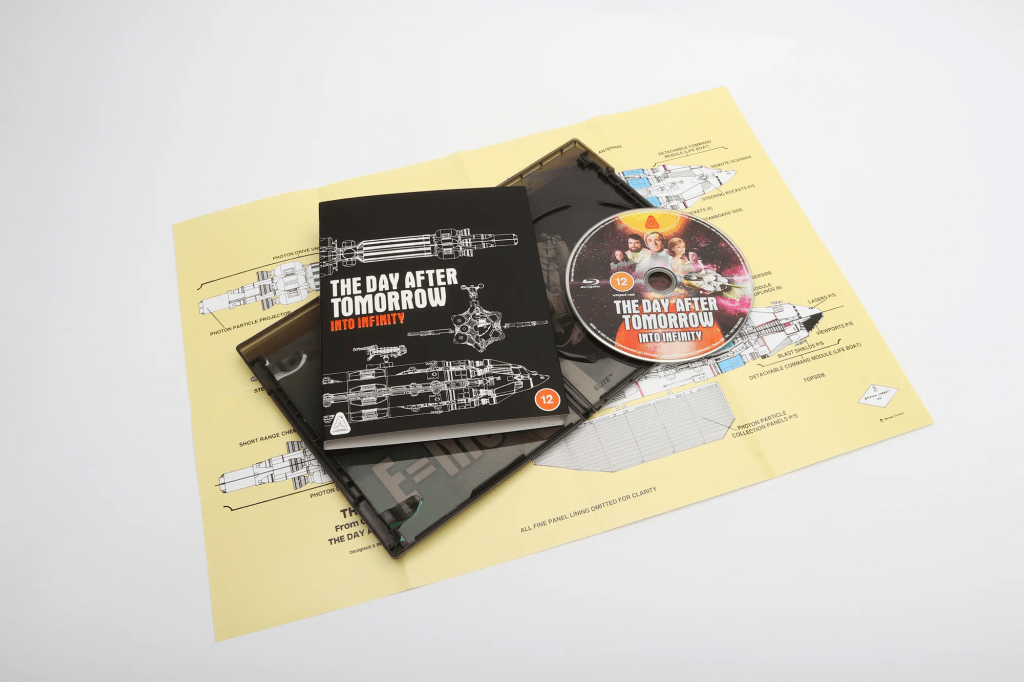

Today, I’ll be examining The Day After Tomorrow: Into Infinity in detail to try and ascertain why I think this plucky little production gets so many things right straight out of the gate. The new, 2024 Blu-ray release of The Day After Tomorrow: Into Infinity from Anderson Entertainment seemed like the perfect opportunity to do so, and I was kindly offered a copy to review. All opinions are my own and freely expressed without sponsorship… so I can say bum as much as I like… I won’t be saying bum again.

The main feature on the Blu-ray opens with this very lovely Anderson Entertainment ident. Obviously that wasn’t there originally… either that or Gerry blew the entire budget on some CGI technology that didn’t yet exist in 1975.

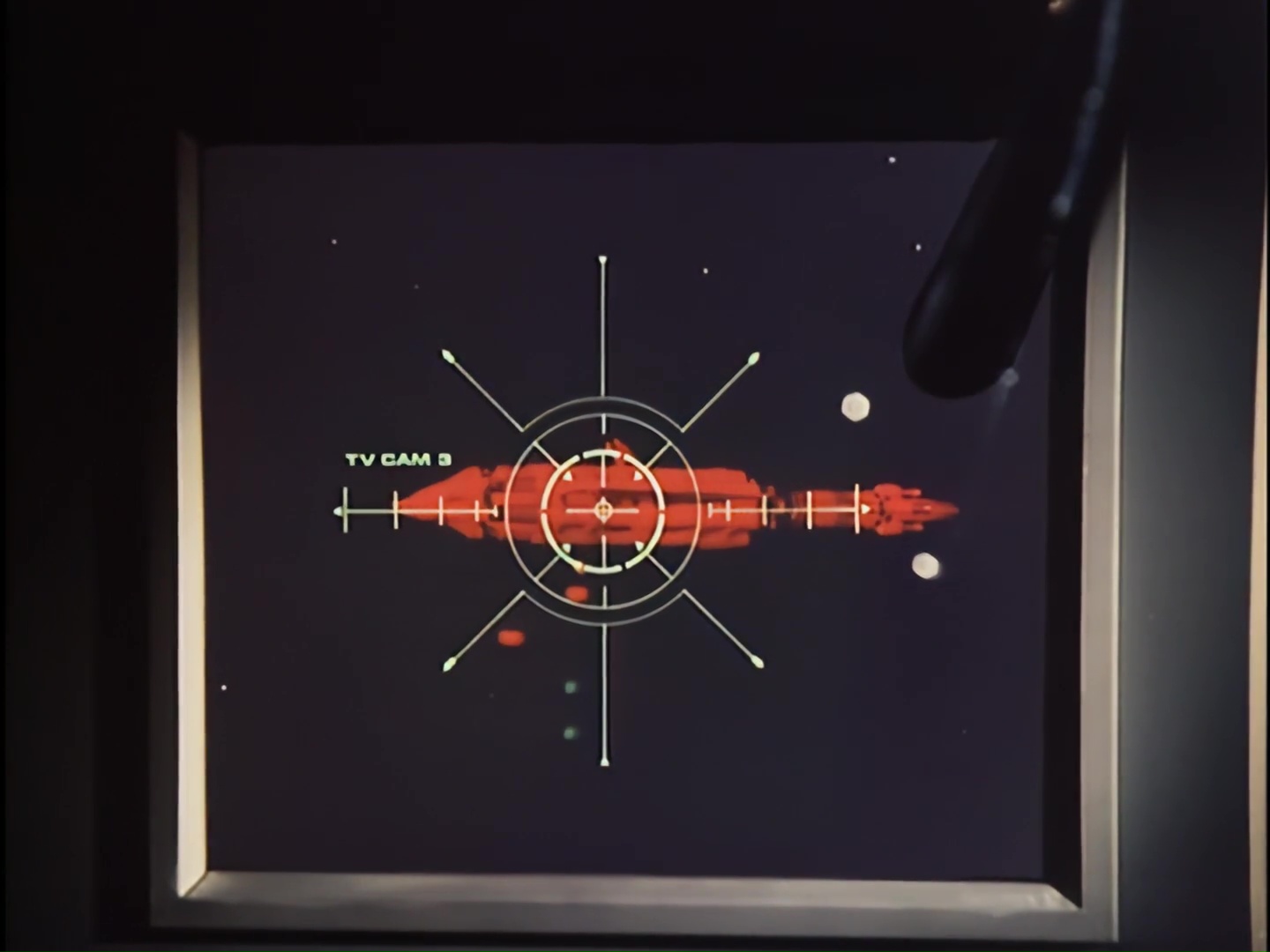

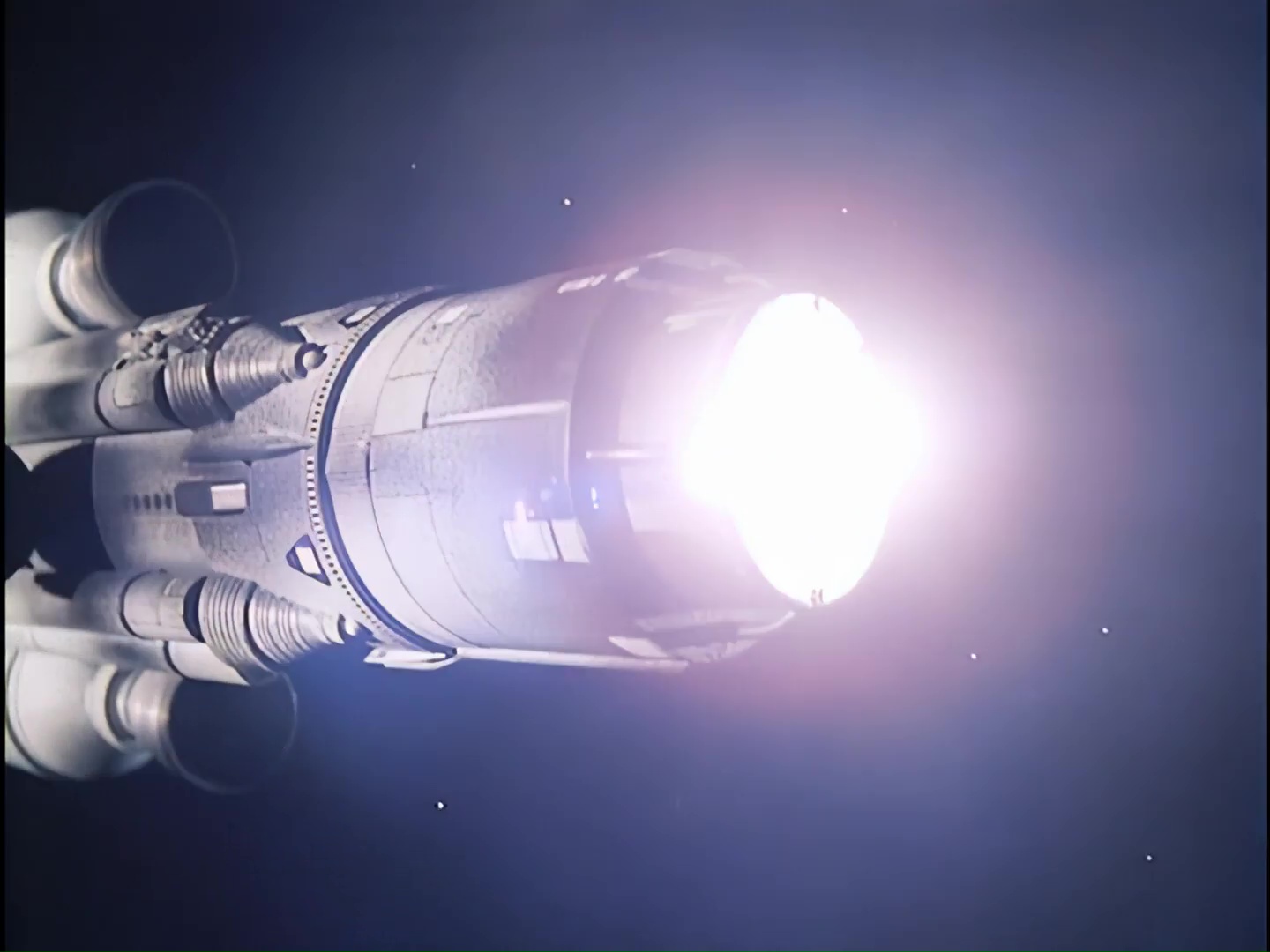

The title sequence is a quick-cutting montage of visually interesting moments from the film because it’s an Anderson production so what else was it going to be? Like the best teaser montages, it doesn’t give too much away about the plot and simply serves to show us what a lot of interesting scrapes we’re going to get into in the next 47 minutes. The special effects shots produced by Brian Johnson’s Space: 1999 team at Bray Studios are particularly prominent and are definitely worth boasting about.

Prior to taking over from Barry Gray as the composer for Space: 1999 Year Two, Derek Wadsworth was commissioned to provide a score for The Day After Tomorrow alongside Steve Coe. The main theme is a perfect fit for the film – full of action, intrigue, and that wonderful sense of optimism and adventure which matches the overall tone of the production. It’s also catchy as heck because of Wadsworth’s deliberate choice to make the main melody singable to the name of the film – which he did again on Space: 1999 Year Two. Controversially perhaps, I actually prefer Wadsworth’s theme for Space: 1999 over Barry Gray’s. Both are amazing, but the Year Two title music just sticks in my head better. Sorry.

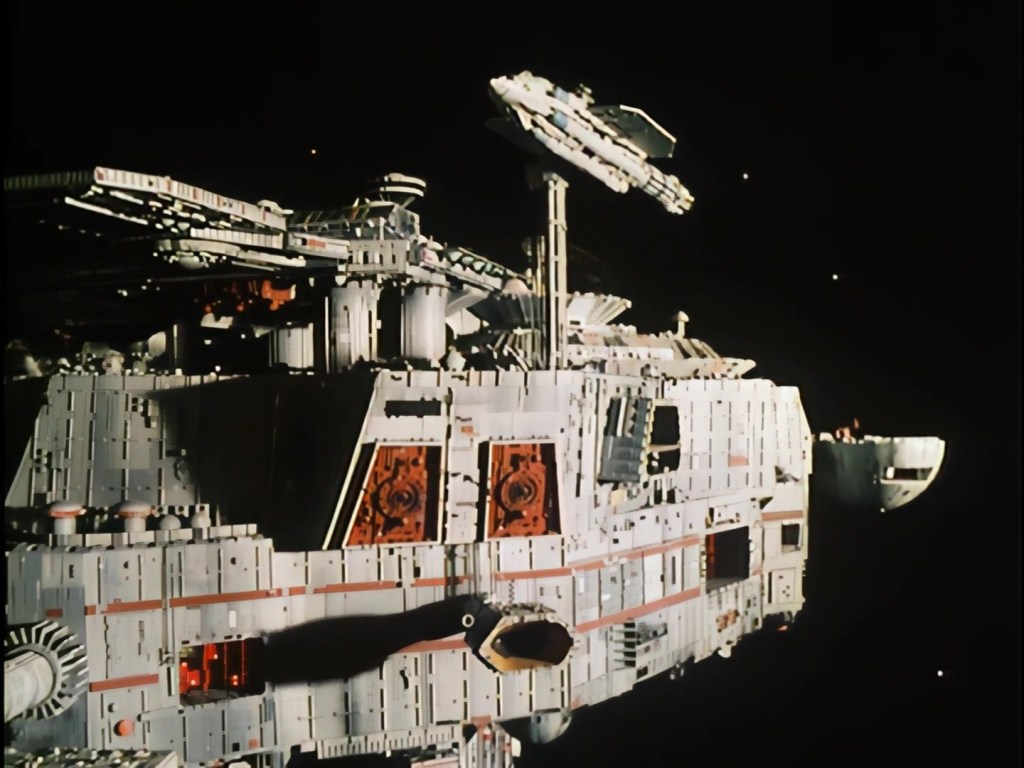

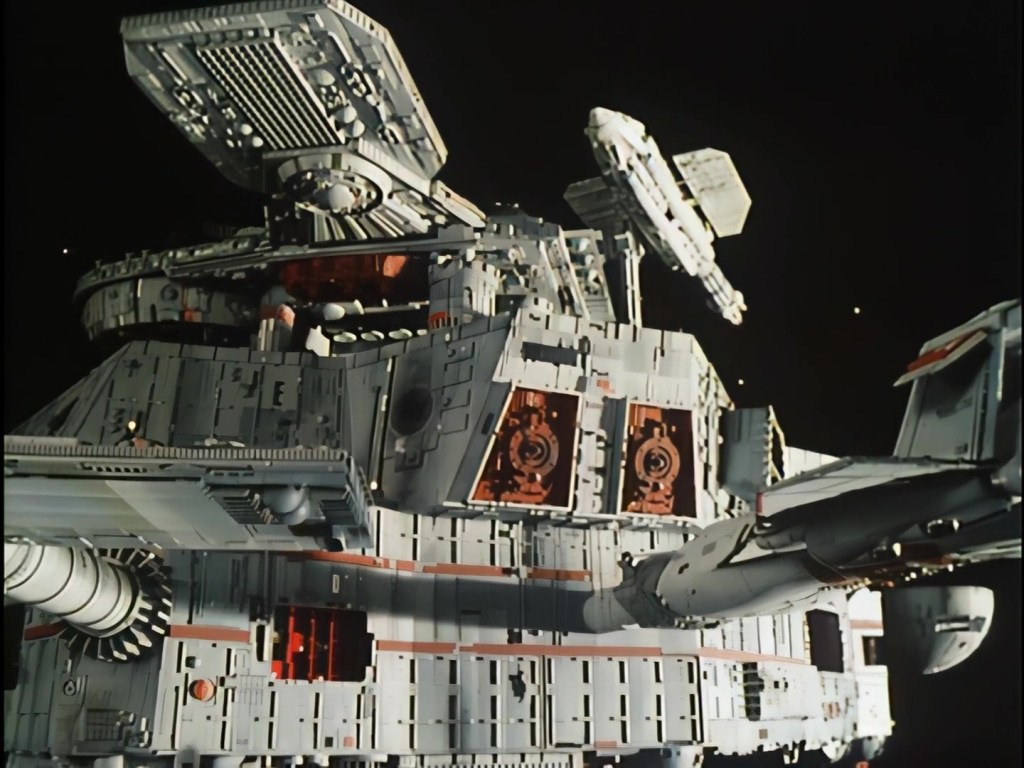

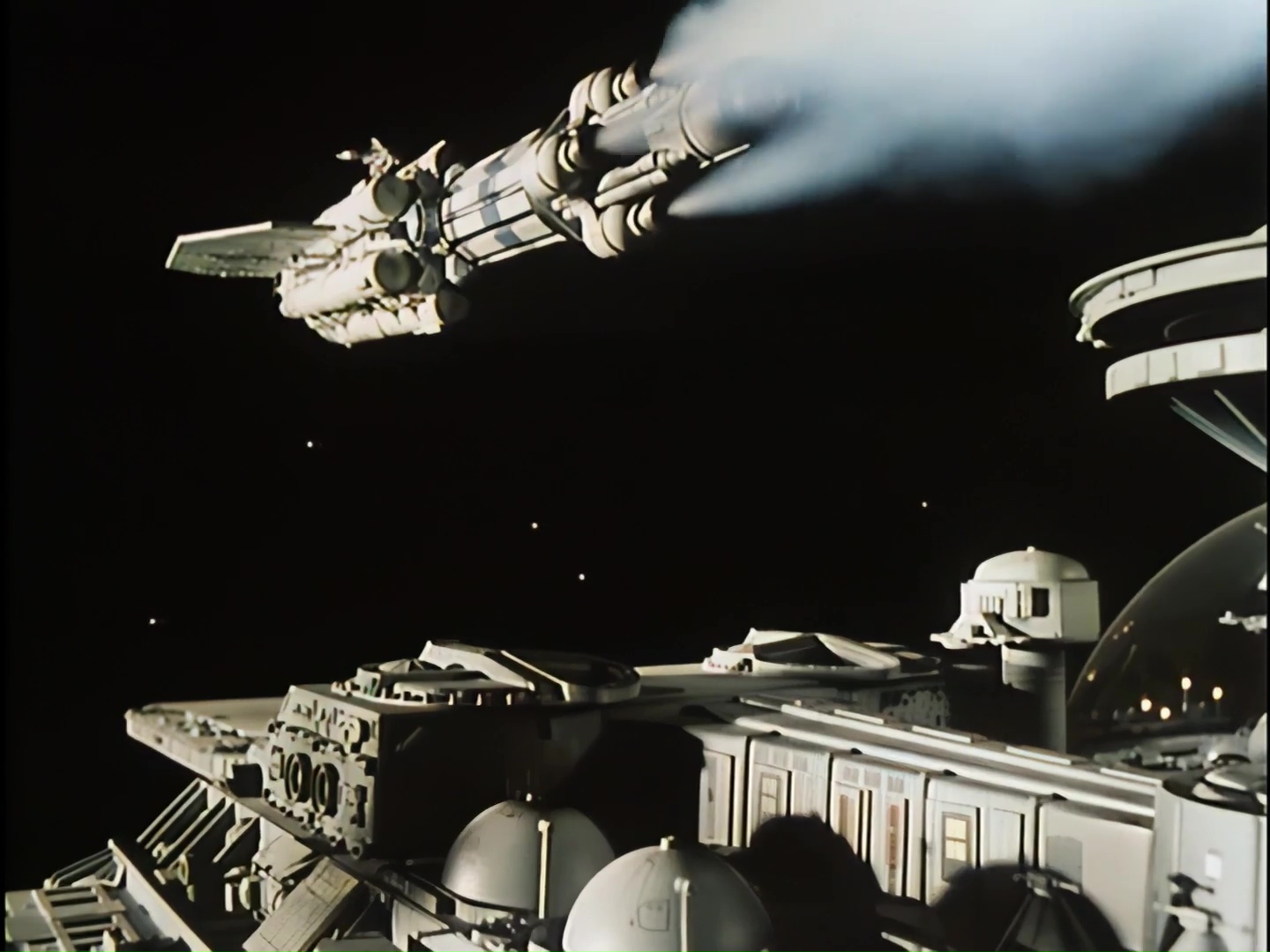

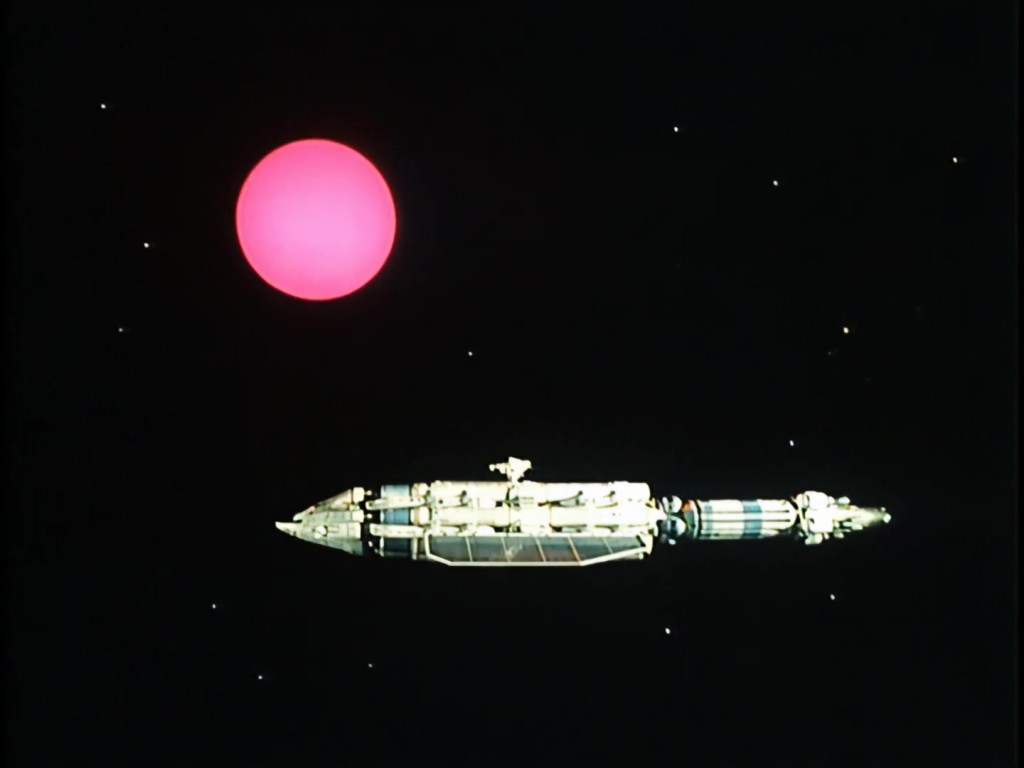

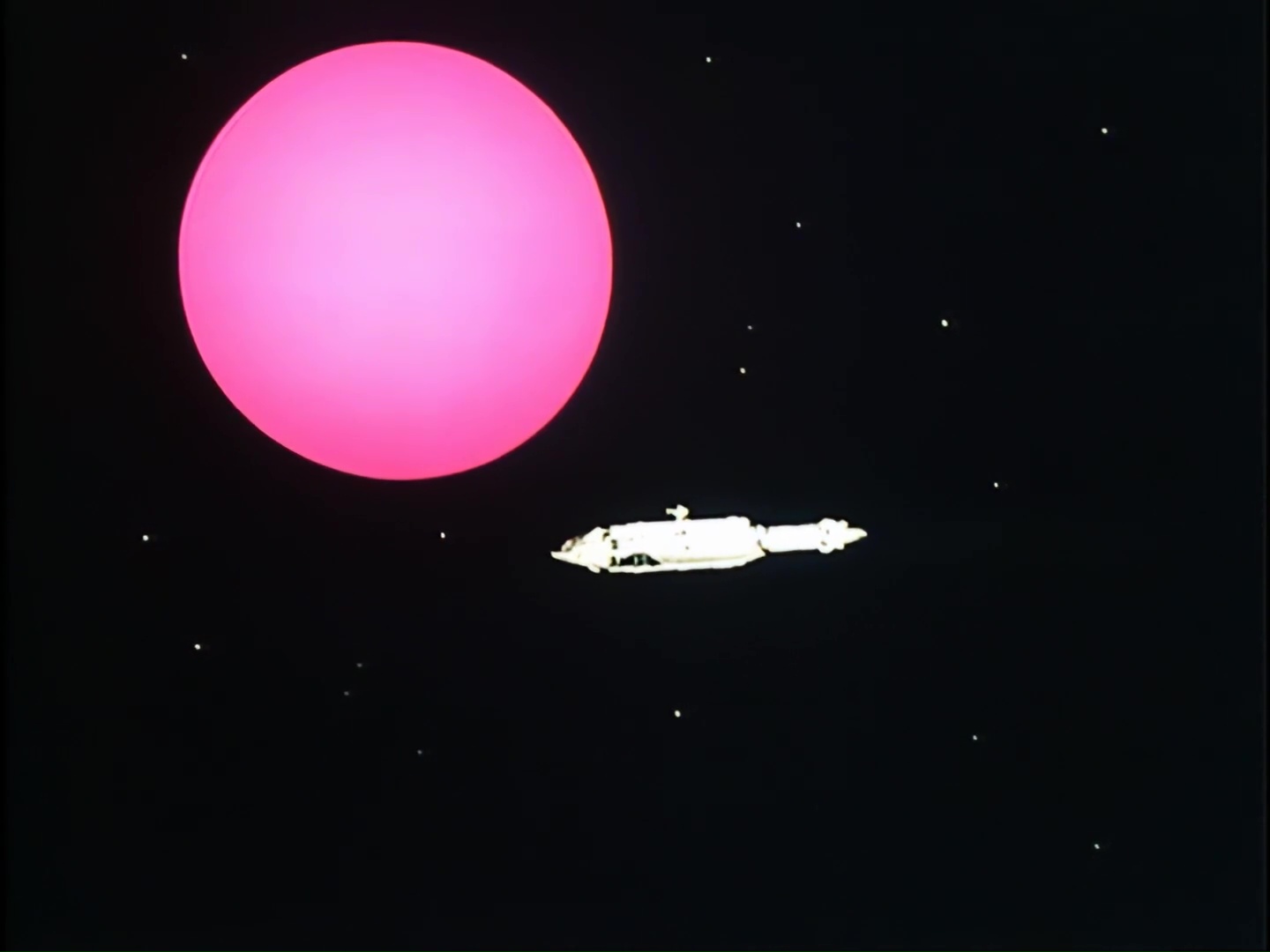

Space Station Delta is a beautiful, big, beefy model. As with so many aspects of this film, it was produced from borrowed elements of Space: 1999 – the spaceship, Daria, from the episode, Mission of the Darians.

Let’s talk about the restoration of The Day After Tomorrow for this Blu-ray release. For most HD releases of Anderson shows from the likes of Network, the closest thing to the original 35mm film source was re-scanned so that all the detail present on the film would be visible in high defintion. Although The Day After Tomorrow was also shot on 35mm film just like Space: 1999 or UFO, only a lower quality 16mm print was available to scan for this release – presumably the same version seen previously on the Lost Worlds of Gerry Anderson DVD in 2015 and prior Fanderson-exclusive releases.

In order to maximise on the amount of detail visible in the available print, Anderson Entertainment chose to upscale the picture with AI technology. Essentially, the computer sharpens up the visuals and fills in gaps in the detail with an approximation of what it thinks should be there. Now, it’s not a perfect system and at least in the year 2024 I don’t think it can replace scanning original film elements in high definition, but the end result of the upscaling is still the best The Day After Tomorrow has ever looked.

When comparing this Blu-ray release to earlier DVD and VHS copies of the film, there’s no question that there’s more clarity in the picture and it looks good. I do think there are a few tiny moments where the AI has struggled to work out what detail to put in and the end result looks a bit like an oil painting, but 99% of the time it delivers a restoration that looks like high defintion quality. In-keeping with the themes of The Day After Tomorrow, I’m excited to see where this technology could take us. If it makes high definition releases of more niche or scarcely available television and film a more financially viable venture, then I’m all for it. The same technique was recently used on Gerry Anderson’s Space Precinct for streaming on ITVX with stunning results.

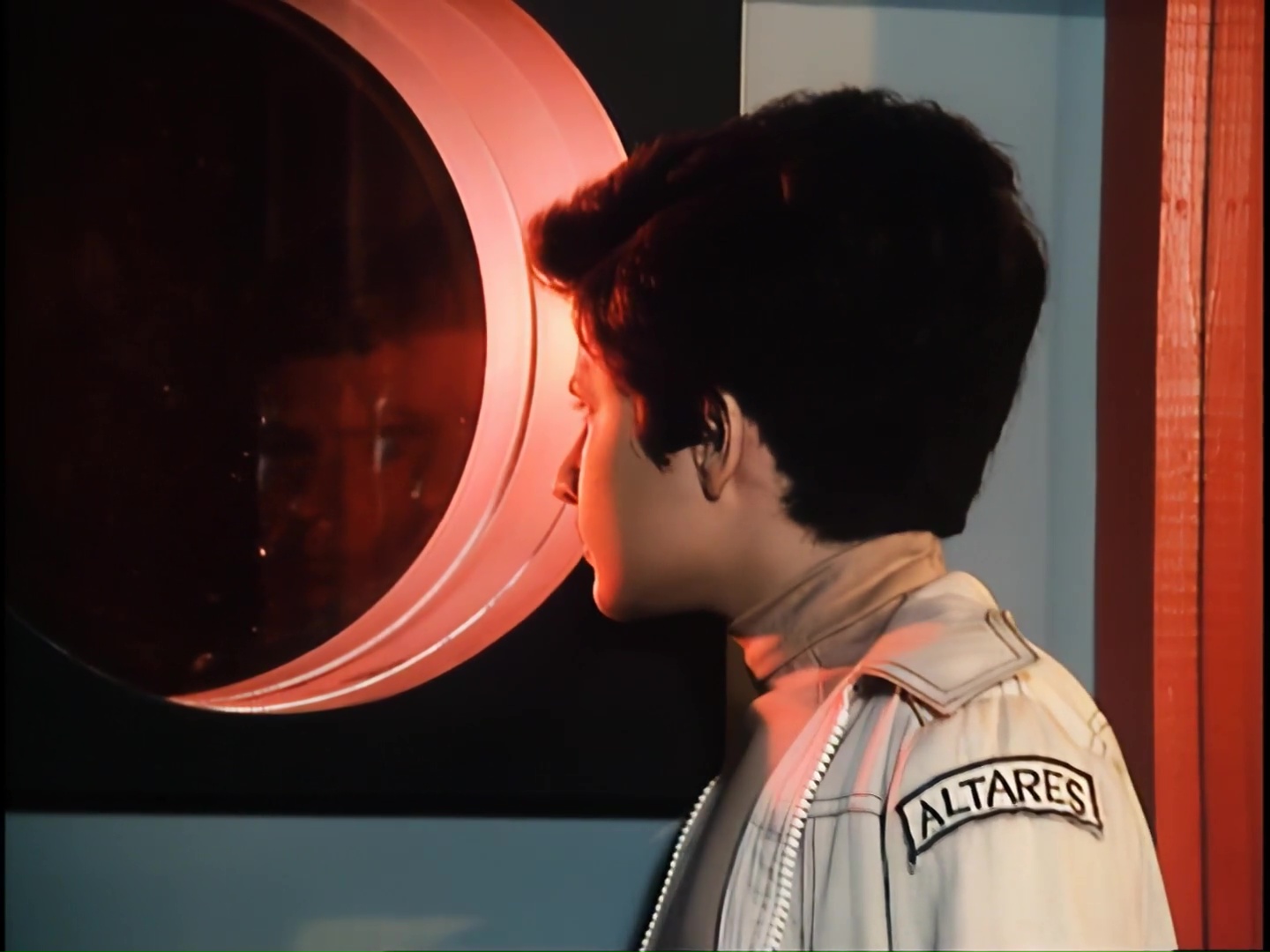

A familiar voice introduces us to the lightship Altares. It’s Ed Bishop, previously seen as Commander Ed Straker in UFO, and the voice of Captain Blue in Captain Scarlet. Gerry Anderson was a great admirer of Bishop’s professionalism and talent, so it’s no wonder that he took any opportunity to hire the American actor again for the narrator role here.

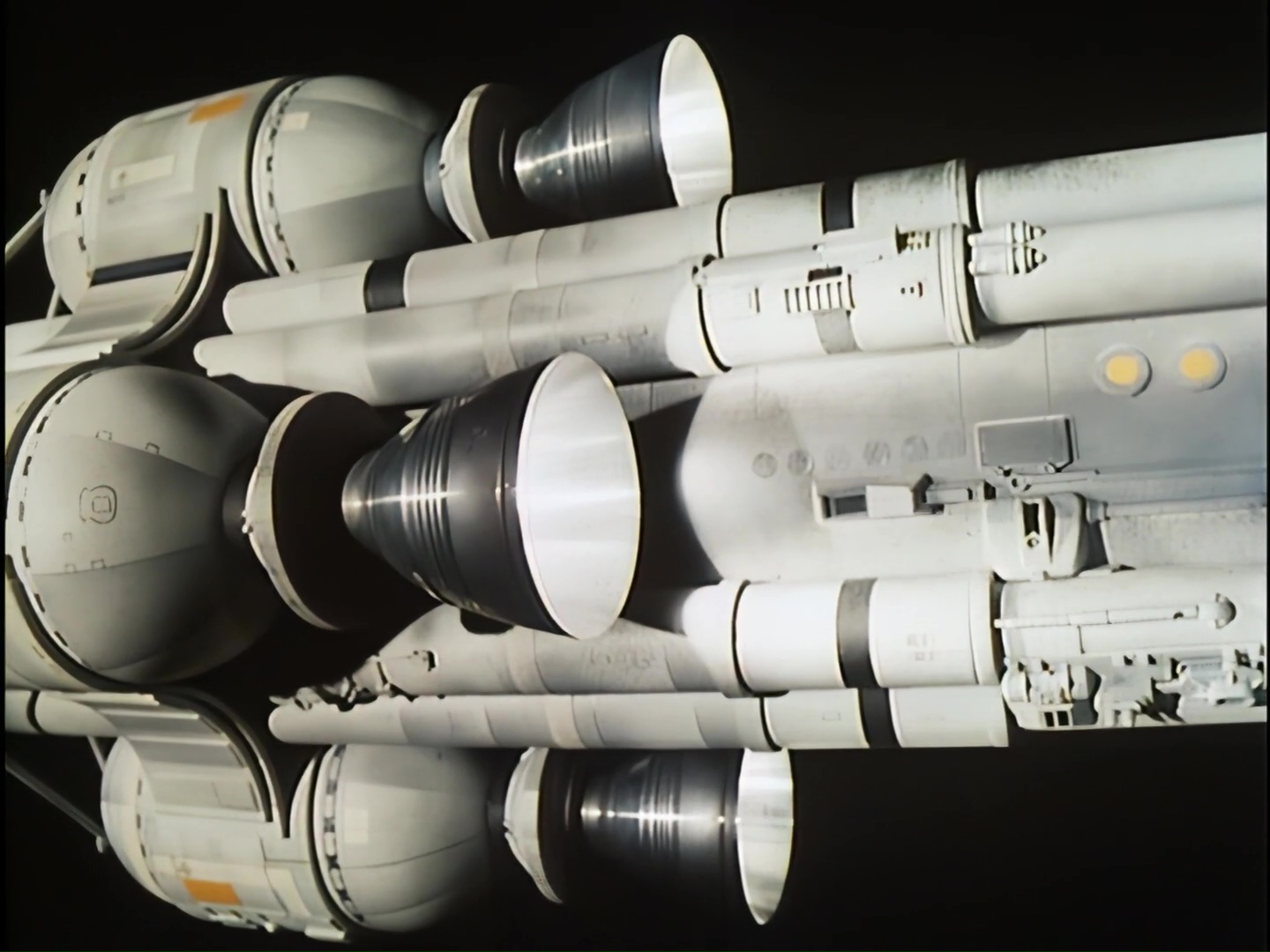

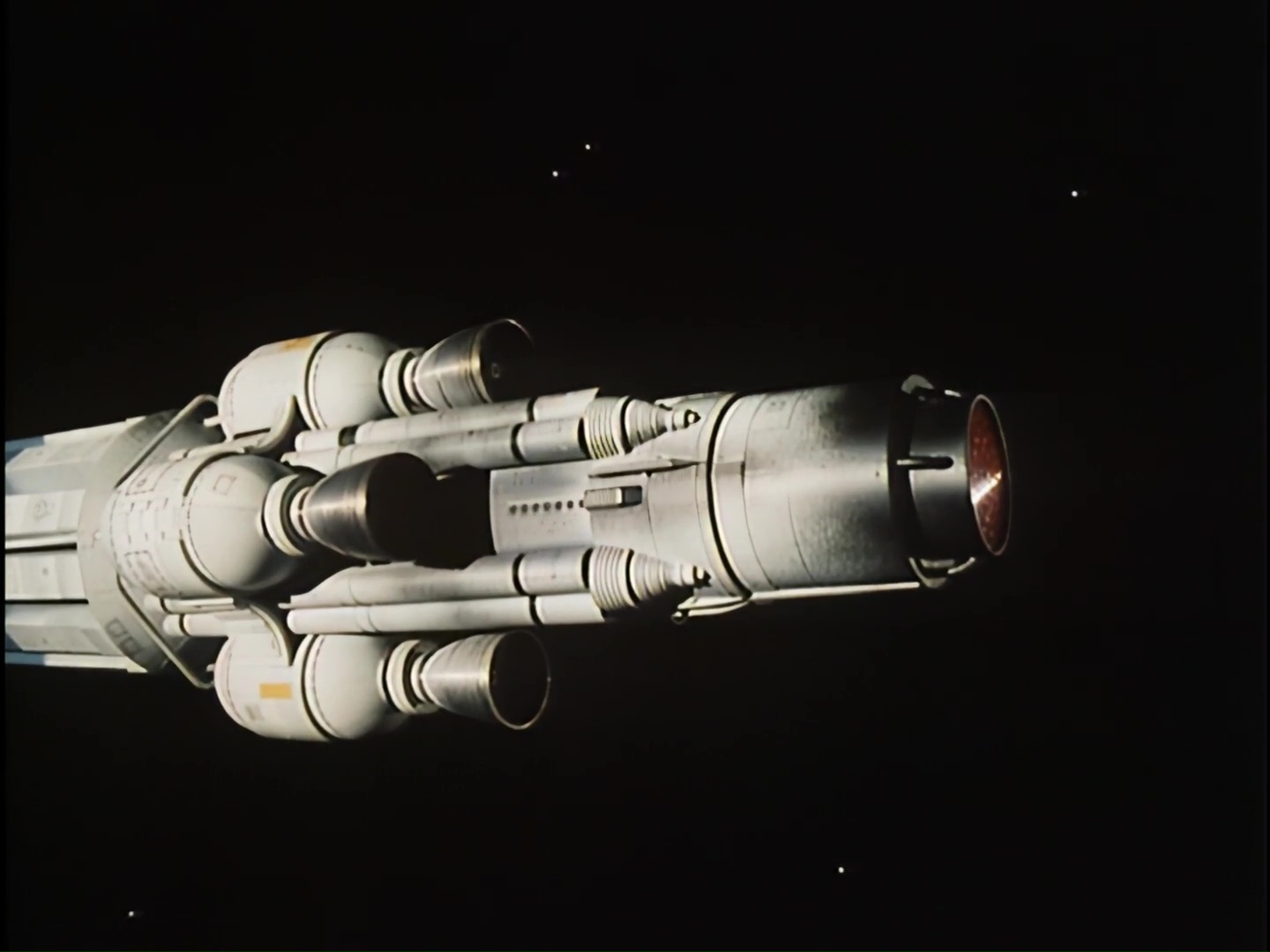

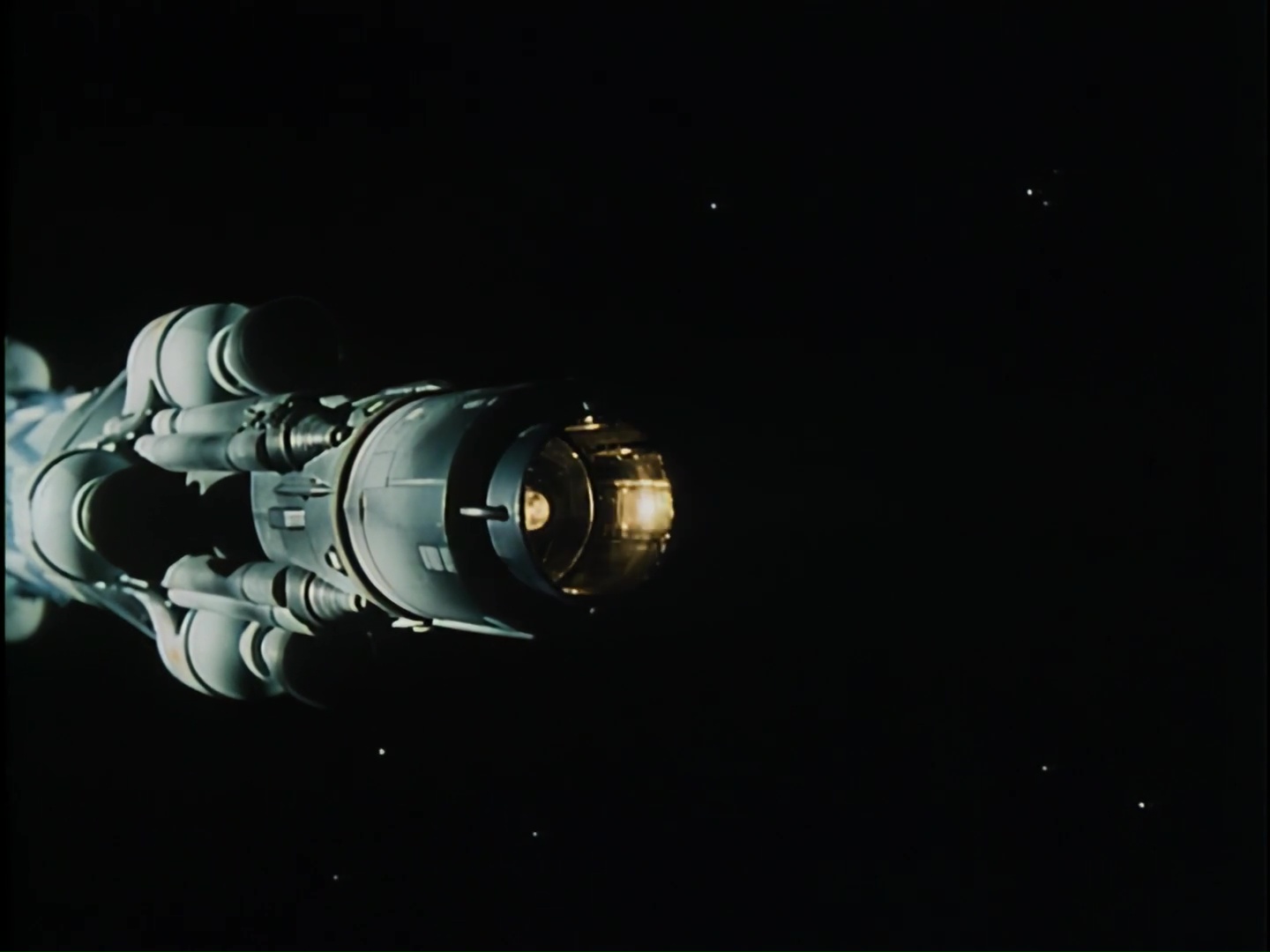

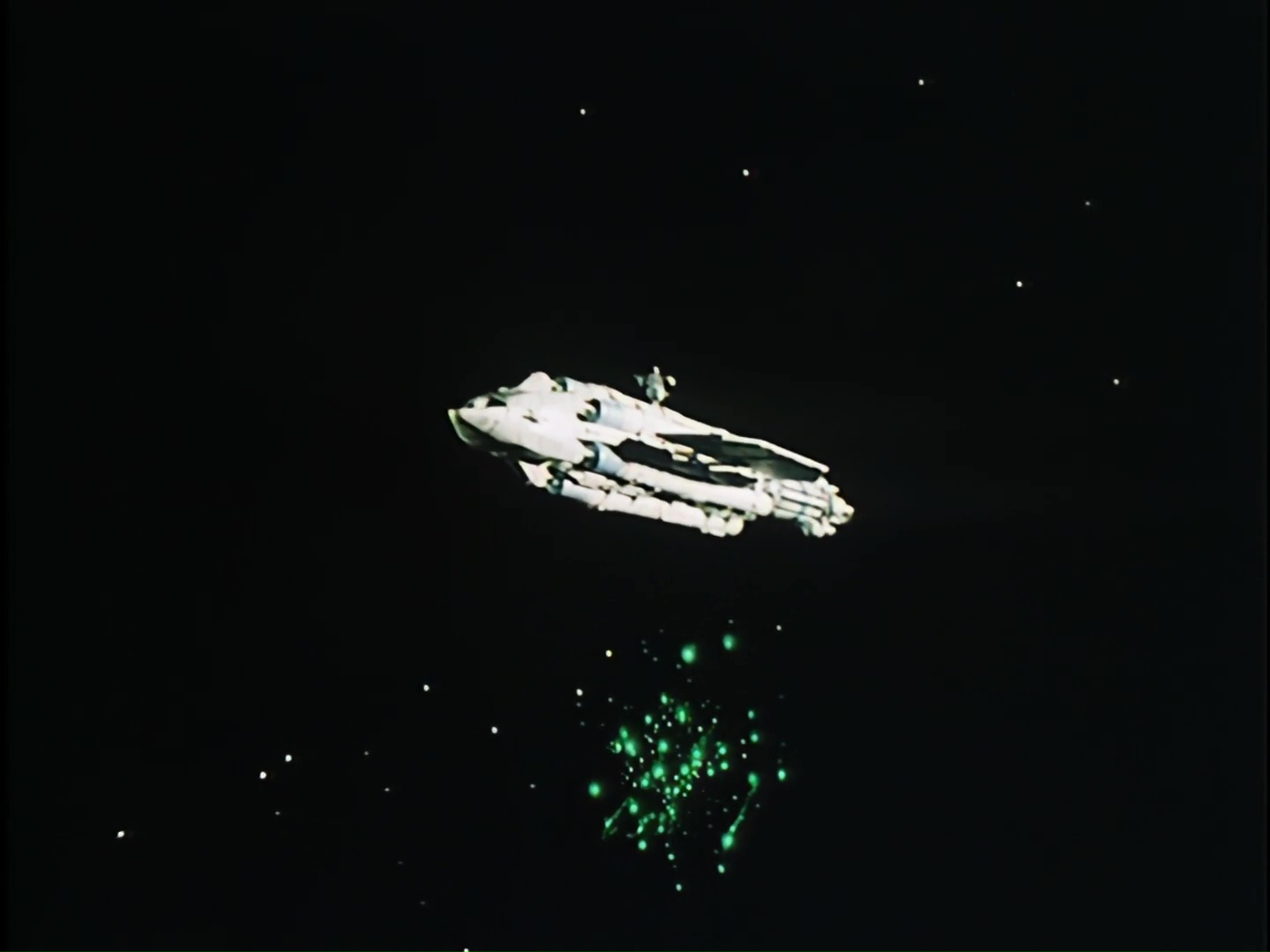

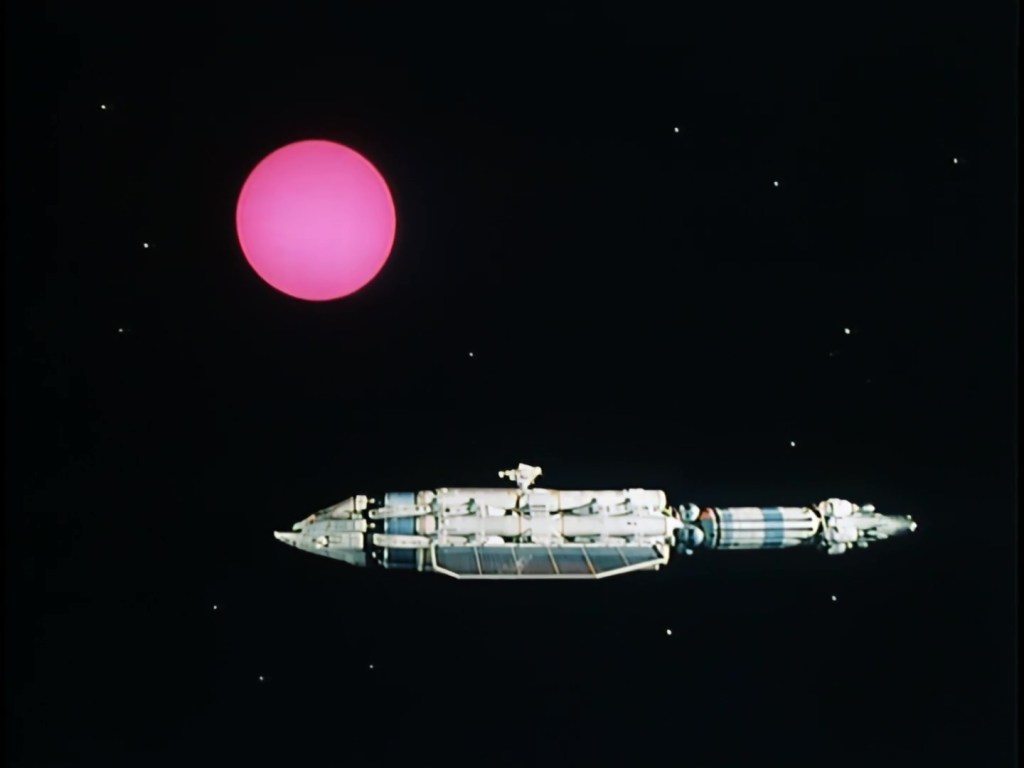

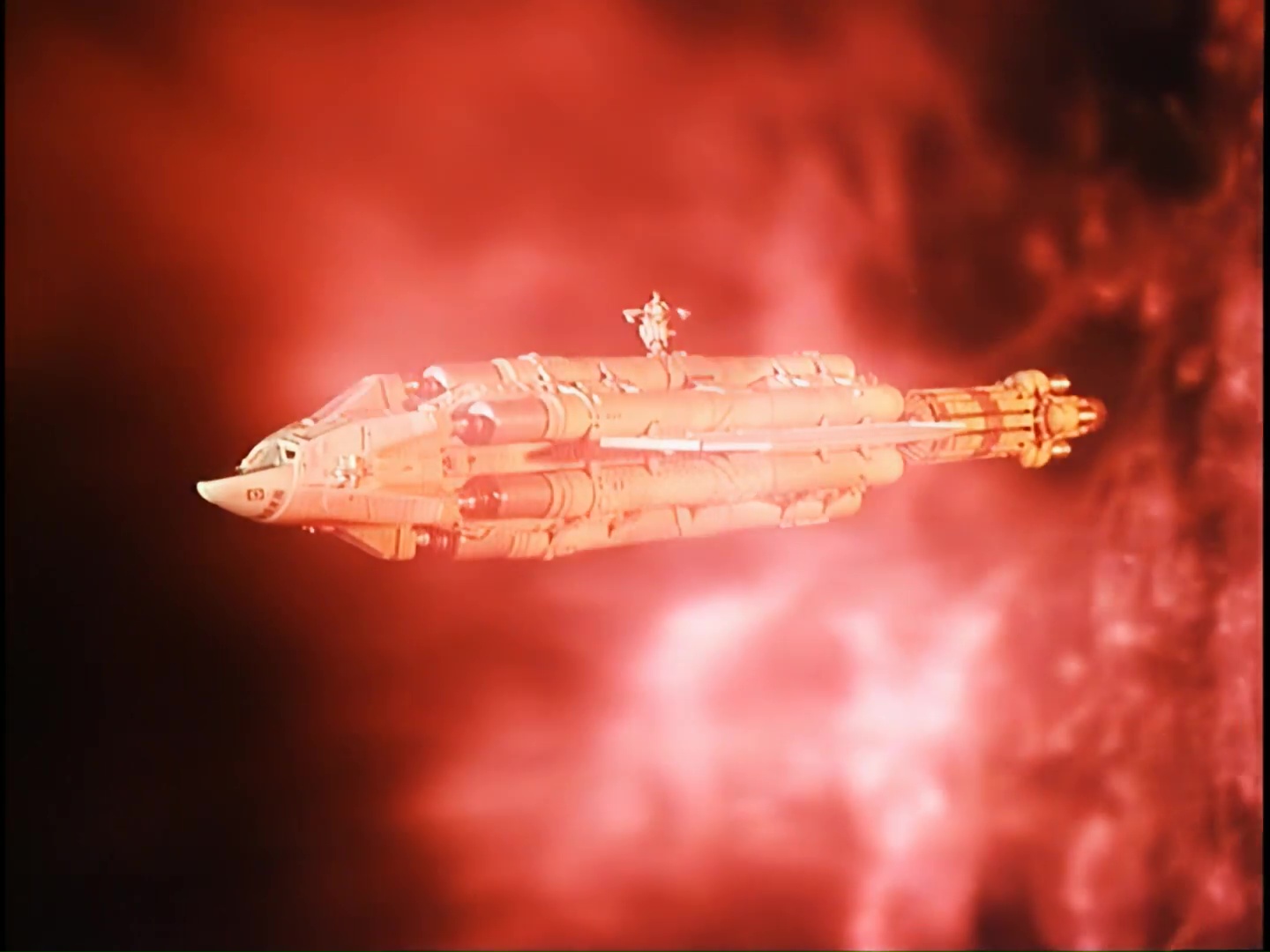

The Altares itself was designed and built by Space: 1999 model maker Martin Bower in the same style as many ships from that series. Bower actually thought he was working on a Space: 1999 commission at the time. There was a six-foot-long model, and a smaller three-foot-long model produced.

Again, I’m going to come along with my controversial Space: 1999 opinions here. Within the wider Anderson canon, the Space: 1999 era of spaceship designs probably isn’t my favourite, so you won’t catch me gushing over the seemingly thousands of different Eagle variants out there like a lot of fans do. However, even if the design isn’t to my taste, I do think Martin Bower does an extraordinary job producing exquisitely detailed models which fit the very realistic approach to space travel portrayed in Space: 1999 and by extension, The Day After Tomorrow. The Altares really looks like it could manage a life-long voyage into the stars and has all sorts of details that we don’t even get to explore within this film. The Blu-ray set is good enough to provide a lovely printed poster of the blueprint for the ship.

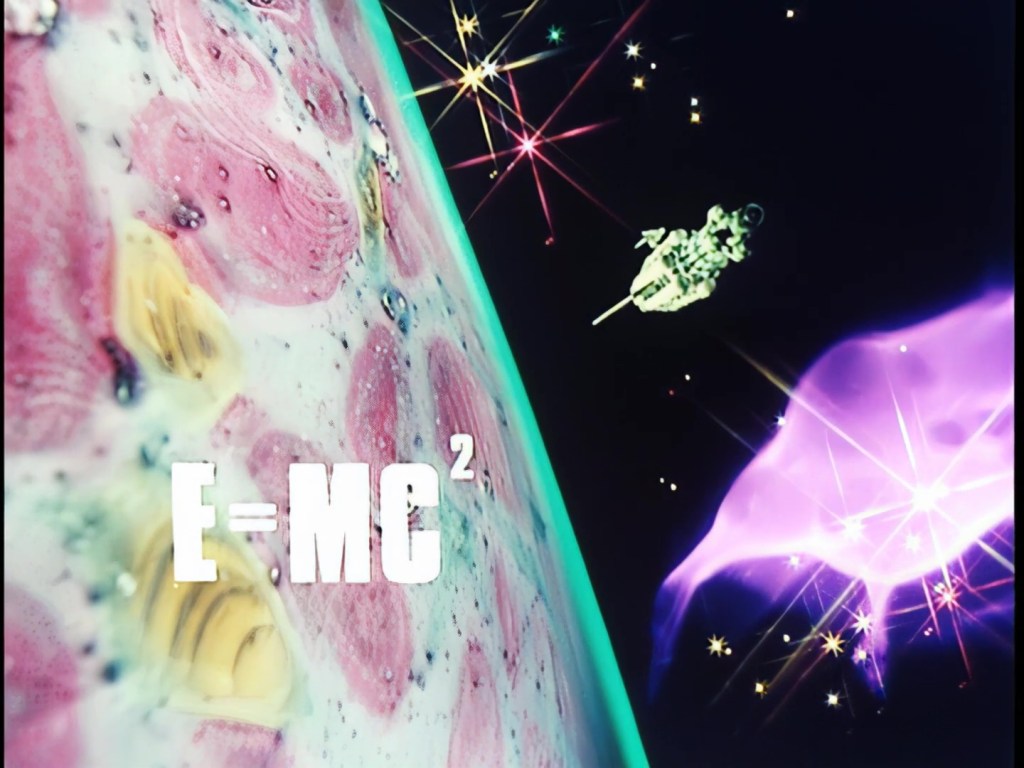

The narrator sets up the premise of the film quite succinctly within a few lines. The Altares is the first ship to harness the power of the photon in order to travel at the speed of light, the consequences of which are outlined in Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. It’s the first of many direct references to Einstein’s theory in the film because frankly that’s what Anderson and writer Johnny Byrne were getting paid for.

I’ve mentioned previously on this blog that I spent much of my GCSE Physics exam with my head in my hands, so I’m not all that well equipped to judge the accuracy of the science stuff in this film. So, in the spirit of the Blu-ray restoration, I’ve harnessed the power of AI to help on that front. I asked the internet’s foremost spouter of utter nonsense, ChatGPT, to explain Einstein’s theory of relativity to me like I was a five-year-old.

Generated by ChatGPT 3.5, February 2024

Okay, imagine you’re on a super-fast merry-go-round with your friend. If you throw a ball to your friend, it might not go straight to them because the merry-go-round is moving. Now, imagine if your merry-go-round is really, really fast, like super-duper fast, like close to the speed of light! Einstein said that if you’re on that super-fast merry-go-round, time can slow down for you compared to someone standing still outside. It’s like time itself is playing a trick on you! Also, Einstein said that if you’re in a really strong gravity, like on a planet with a lot of gravity, time can also slow down for you compared to someone in a weaker gravity place. So, basically, Einstein’s theory of relativity is all about how time and space can change depending on how fast you’re going and how much gravity is pulling on you. Cool, huh?

No, not cool, huh. If I was on a merry-go-round travelling at the speed of light, I’d be too busy chucking up my guts to notice time slowing down for anyone else. Jeez, The Day After Tomorrow definitely wins all the points for explaining Einstein’s theory best.

Our friendly narrator takes a moment to contemplate the vastness of the universe and humanity’s position in it. Earth = not all that big. Sun = not all that hot. Milky Way = not all that unique. “A universe not only stranger than we imagine, but stranger than we can imagine.” What a wonderfully abstract concept for an educational special aimed at children and teens. So often the approach with this kind of subject is to put it in terms that a child can understand so that they can relate to it and stop asking questions (see ChatGPT’s ludicrous tale of Einstein’s merry-go-round above).

The Day After Tomorrow immediately counters that dumbing-down approach by stating outright that we will never get a grasp on just how big and limitless the universe is. Space is not just mysterious, it’s totally unknowable by its very nature. Humanity is going into any space exploration endeavour knowing that it’s impossible to find all the answers. I think that’s a challenging but refreshing, awe-inspiring perspective for a young mind. Since we can’t learn everything there is to know about the universe, the focus switches from understanding it to experiencing it. That’s one of the messages of The Day After Tomorrow in a nutshell – the Altares crew don’t always understand what’s happening to them, but they’re sure as heck going to do everything they can to live through it, and you should do the same.

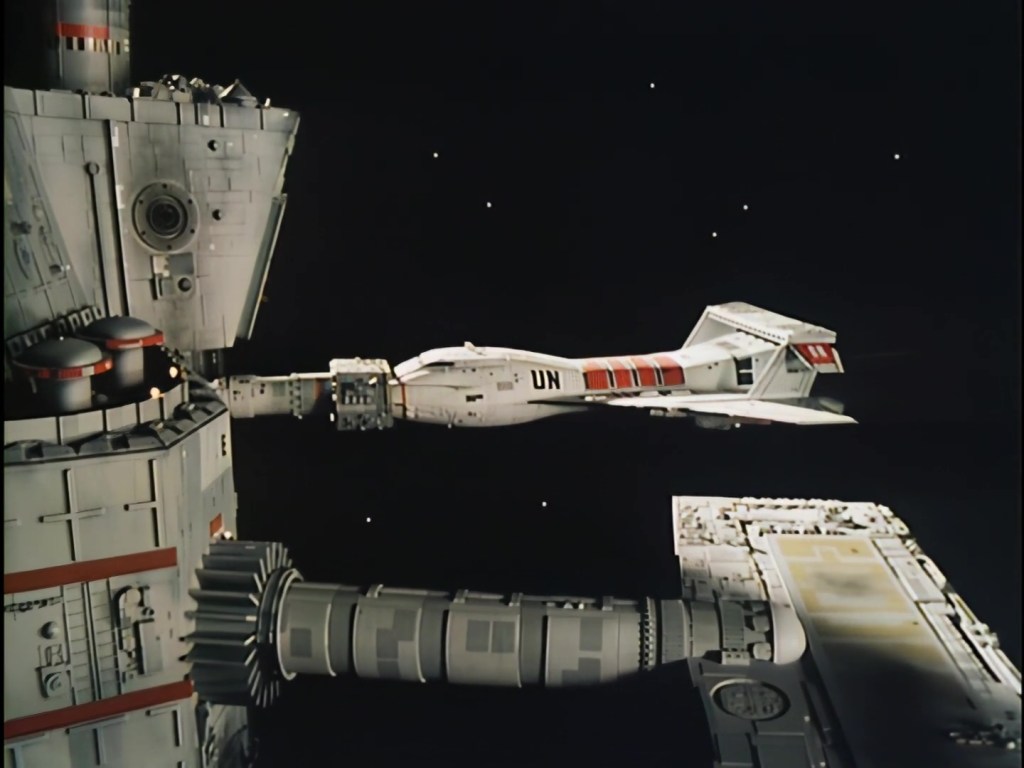

The United Nations shuttle craft docks with Delta. As with the politics in many other Anderson productions, the world presents a united front. There isn’t any suggestion of different countries or superpowers competing to conquer space first. Instead, the mission of the Altares is an entirely human endeavour, not a political one.

The narrator explains that the first stage of the Altares mission is to travel to Alpha Centauri, “24 million million miles from Earth” – a cleverly written line which avoids the cultural difference in the definition of billion versus trillion between the US and the UK.

Remember what I said earlier about some shots in this looking like an oil painting? Well that isn’t strictly relevant here because most of this shot actually is a matte painting so of course it’s going to look like one. The Day After Tomorrow was produced on a tiny budget, and this is one of the more ambitious special effects shots in the entire production. It’s very similar to a shot used in Space: 1999‘s Mission of the Darians. Now, the illusion would probably pay off quite well if it weren’t for the tiny issue of Jane, played by Katharine Levy, running a little too close to the edge where the painting meets the floor of the sound stage, and half her body disappearing for a split second as a result. Never mind, it’s still pretty cool.

As the narrator explains, the time dilation effect outlined in Einstein’s theory means it’s probably a good idea for families to travel in complete units to avoid any freaky age discrepancies later. Let’s give ChatGPT another go at explaining time dilation to a five-year-old…

Generated by ChatGPT 3.5, February 2024

Okay, imagine you have two special clocks. One clock is on a rocket ship, and the other is on the ground. The clock on the rocket ship starts ticking when the rocket takes off. Now, let’s say the rocket zooms through space really, really fast, almost as fast as a superhero! Meanwhile, the clock on the ground stays still. When the rocket comes back to Earth, something strange has happened. Even though both clocks were ticking the whole time, the clock on the rocket shows less time has passed compared to the clock on the ground! It’s like the rocket clock had a superpower to slow down time. This is called time dilation. Einstein figured out that when things move really fast, time slows down for them compared to things that aren’t moving as fast. So, if you were on that speedy rocket, time would feel a bit different for you compared to your friends waiting for you back on Earth!

How dare ChatGPT assume I have friends.

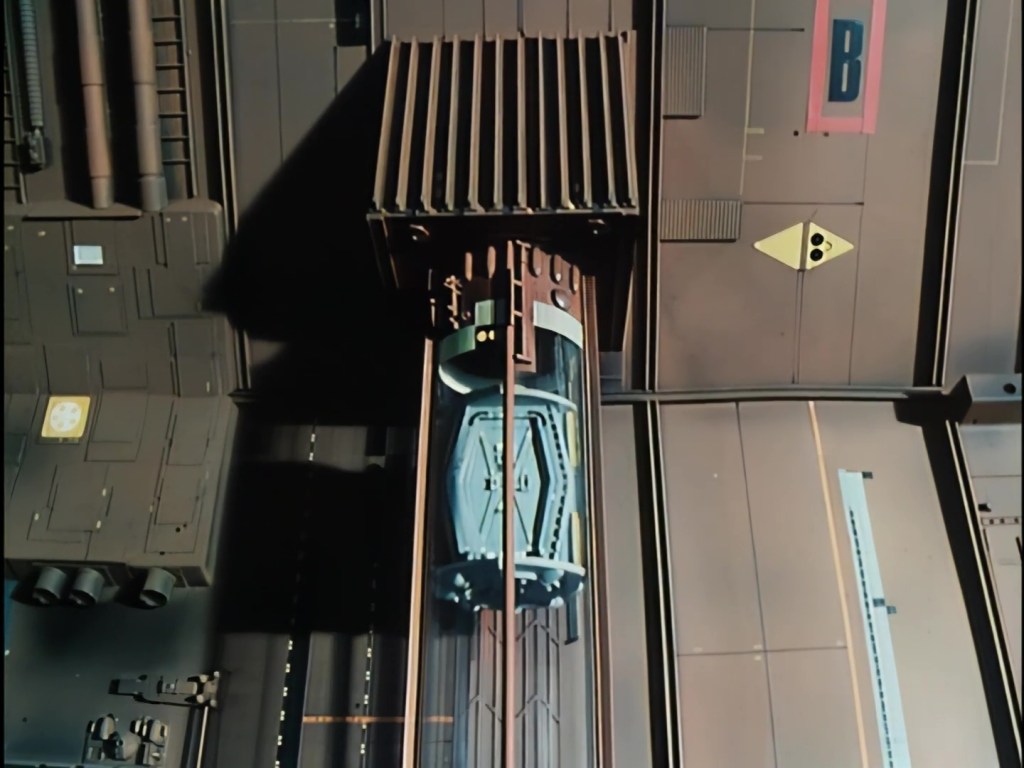

Here’s a scene which absolutely beautifully sets the tone for the whole film. It’s all super serious business as the crew gets into the lift to board the Altares. But these are human beings and a family. And sometimes human beings inexplicably form familial bonds with small furry animals. With an enormous sense of strength and dignity, it’s time for Jane Masters to say goodbye to Spring, her beloved pet dog. Would it have made more sense to say their farewells down on Earth so that the dog didn’t have to go through the stress of journeying to Space Station Delta? Possibly, although I guess in the future we’ll have made space travel entirely more comfortable for all forms of life. Spring is portrayed by none other than Johnny Byrne’s own dog, Bones. In the delightful Memories of Infinity documentary on this Blu-ray, Katharine Levy is keen to highlight that Bones did not make a nuisance of himself on the set. Gerry Anderson only hires the best.

Speaking of the best, what a lovely bit of acting from Katharine Levy, Don Fellowes, and the rest of the cast during this tender moment. It’s not too sickly sweet, or too cold, but just the right emotional level to demonstrate the sacrifices that the crew of the Altares are making for this mission. To go from Ed Bishop grandly expositing about the hugeness of the universe, to an innocent dog and a teenage girl parting ways with the same level of sincerity points to a script writer and director with a very clear understanding of the film’s goal and intended audience.

It’s a tonal balance which, frankly, Space: 1999 struggled with at opposite ends of the spectrum. Largely, Space: 1999 Year One is considered too emotionally detatched and stuffy, and Year Two is trying disgustingly hard to be nice and fluffy. There are really great moments in Year One and Year Two when the right balance is met, but it’s not consistent. The Day After Tomorrow hits it perfectly straight off the bat in my opinion.

Alas, one of the things often working against this film’s publicity is the fact that nobody can decide what to call it. Is it The Day After Tomorrow? Into Infinity? The Day After Tomorrow: Into Infinity? And that was all complicated further when the 2004 disaster movie, The Day After Tomorrow, was released. The way I understand it is that “The Day After Tomorrow” would have been the title of the television series had a full batch of episodes been commissioned, and “Into Infinity” was the name of the first episode. When the film was broadcast by the BBC in 1976, they chose to cut “The Day After Tomorrow” part out so the title was just Into Infinity. In 2017, Anderson Entertainment published a new novelisation of the film called Gerry Anderson’s Into Infinity Book One: The Day After Tomorrow, and a sequel in 2019 entitled Gerry Anderson’s Into Infinity Book Two: Planetfall. Just to make it even more confusing, the first edition of the first book was originally called Gerry Anderson’s The Day After Tomorrow Into Infinity. Look, whatever you want to call it is fine with me. I’ll know what you’re talking about even if nobody else does.

An exciting reprise of the theme music accompanies the rest of the credits and the tiny elevator’s journey up through the vast structures of Space Station Delta towards the Altares.

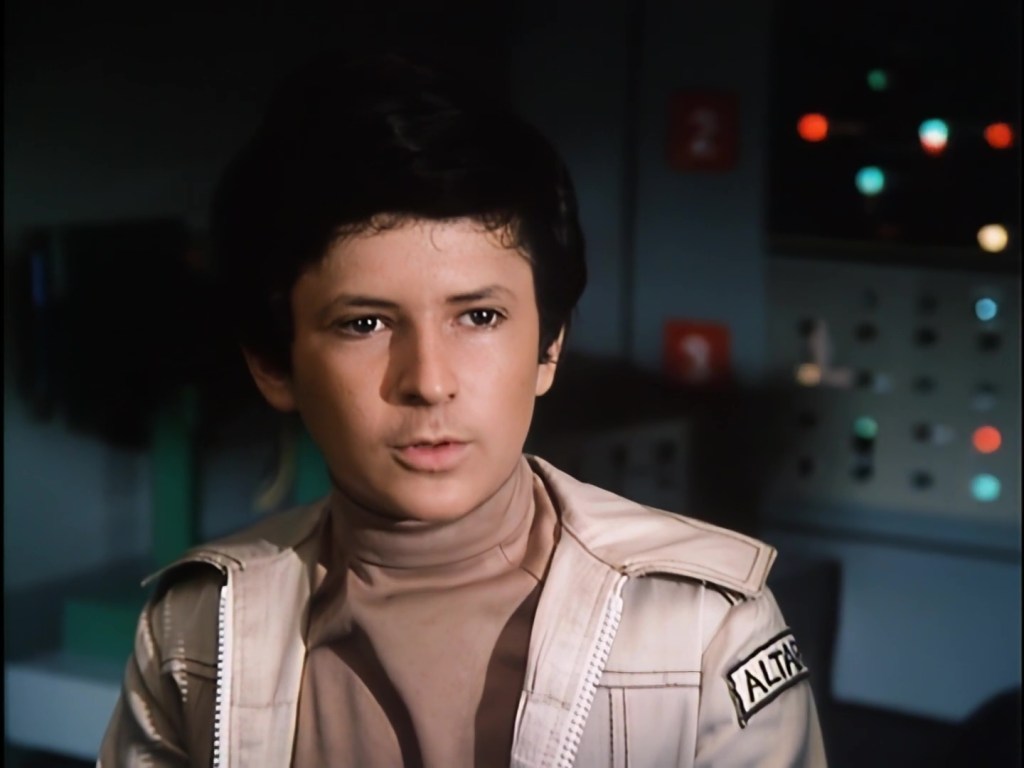

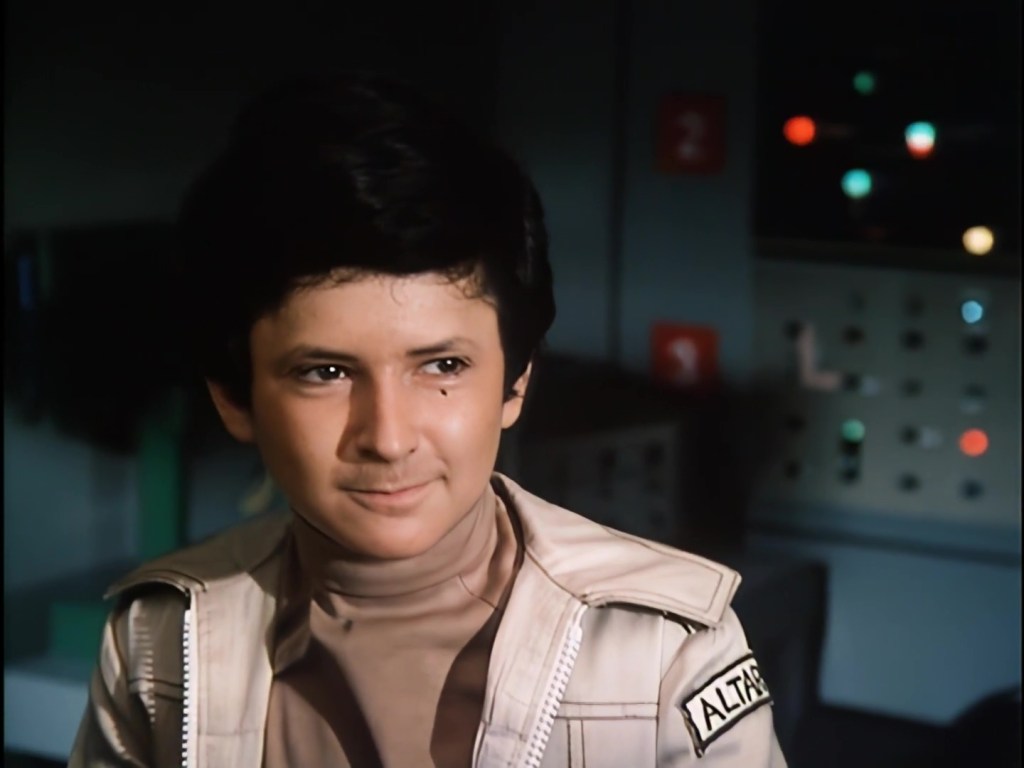

David Bowen, played by sixteen-year-old Martin Lev, is given the monumental task of opening the jazzy orange door. He jabs buttons confidently and I like it. While shooting The Day After Tomorrow at Pinewood, Martin Lev was also playing the part of Dandy Dan in Bugsy Malone. After Bugsy Malone he did not return to the screen, but instead turned to a career in theatre with a number of productions at The Questors Theatre. Tragically, Lev committed suicide in 1992, having suffered with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) for many years. I was amazed to learn that he was sixteen when filming The Day After Tomorrow. He looks much younger, and yet plays the role with the maturity of someone much older. We’ll discuss it in more detail later because there’s a lot to explore with both Martin Lev and Katharine Levy’s performances as the two youngsters in the cast.

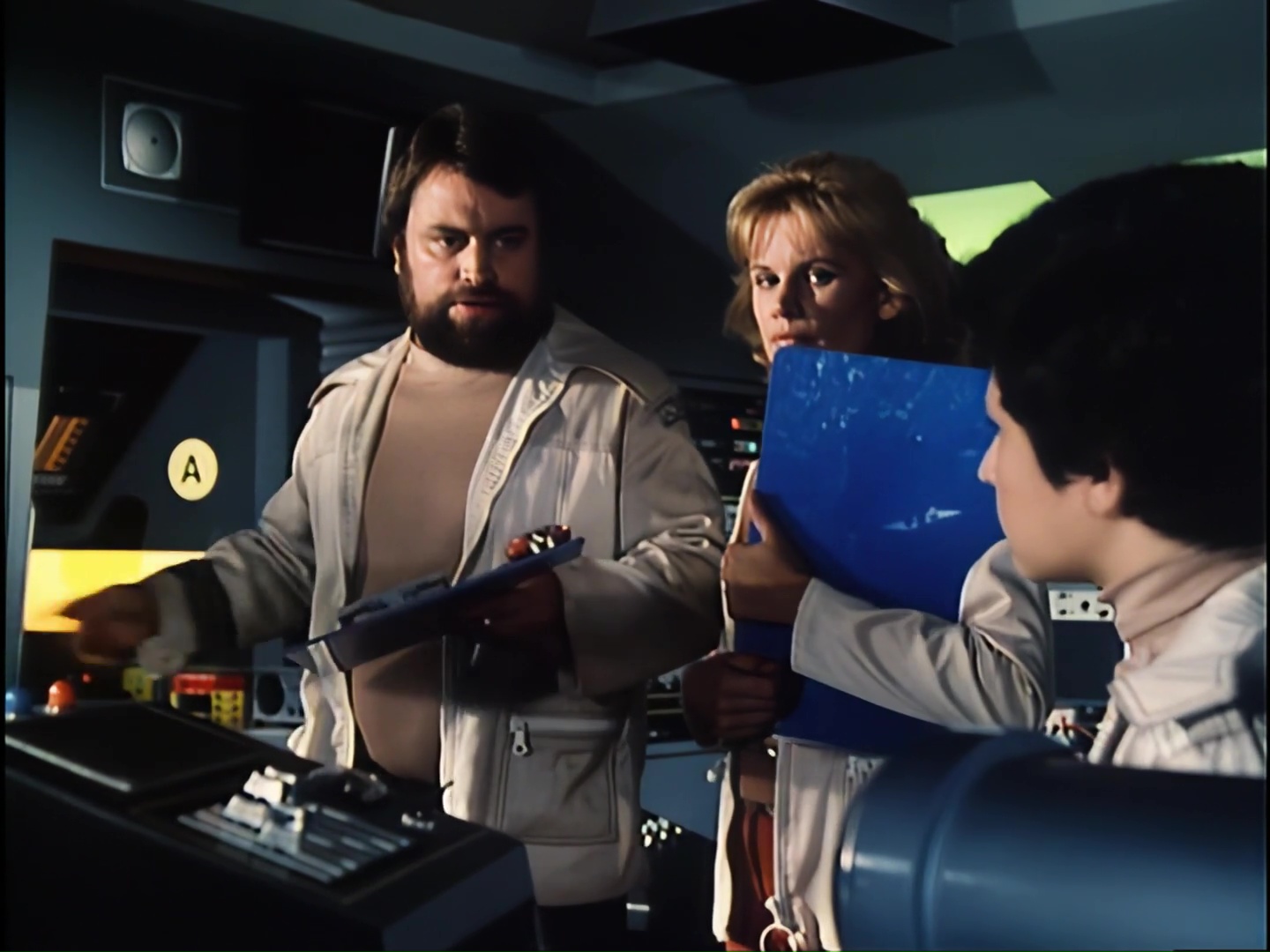

As soon as they enter the ship, everyone gets to work. Young or old, man or woman, everyone in this combined family of the future has a job to do. Of course, many prior Anderson productions have explored the tantalising conflict and/or harmony to be found in combining work life with family life. The Shores and the Tracys make it work for them. The Zeros and the Strakers not so much. Again, The Day After Tomorrow has the perfect balance of family warmth and professional atmosphere. Just in this moment alone, the crew may be working hard on their assigned tasks, but they also have little opportunities to exchange friendly looks with each other and establish the relationships between them without any clunky dialogue to explain who’s who. It’s a very clever bit of direction from Space: 1999 veteran, Charles Crichton.

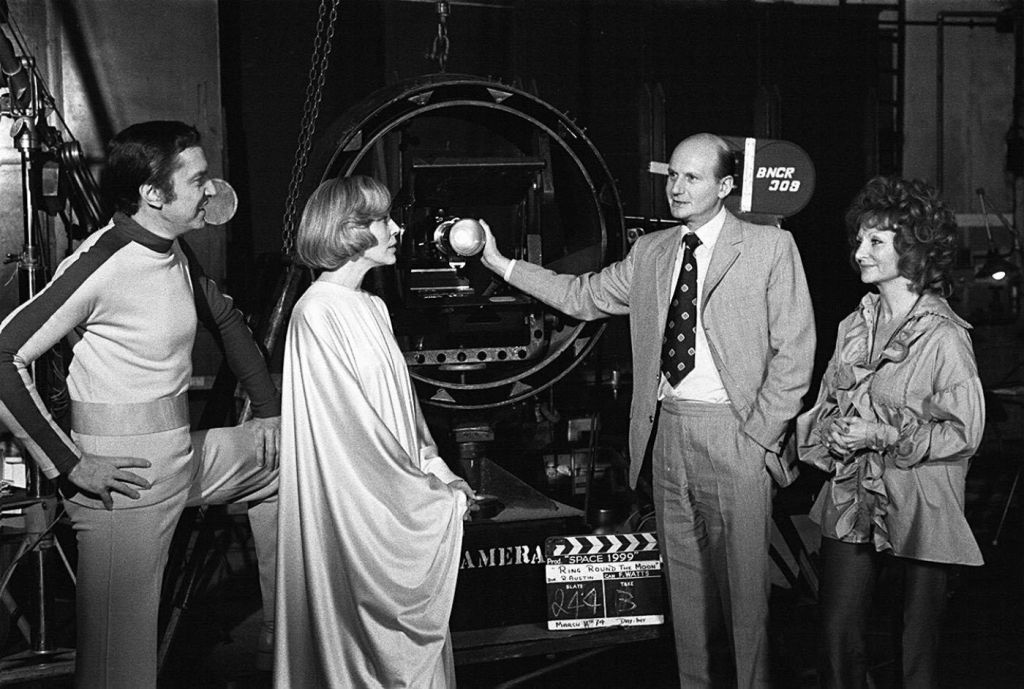

Captain Harry Masters and his daughter, Jane, take their seats at the main controls and start making pre-flight checks. Again, it’s all done with that fine balance between familial warmth and total professionalism. Nick Tate is perfectly casting for the role. As Eagle pilot Alan Carter in Space: 1999, he had been responsible for bringing a great deal of the desperately needed warmth to the first season. In between seasons of Space: 1999, the charismatic actor was playing the role of Brother Victor in The Devil’s Playground in his home country of Australia. He was flown back to England for the 10-day shoot at Pinewood for The Day After Tomorrow. As soon as principal photography was completed on August 1, 1975, Tate returned immediately to Australia to be with his dying mother, actress Neva Carr Glyn, who passed away on August 10. Nick Tate’s father, John Tate, was also an accomplished actor with an Anderson connection, having provided uncredited additional voices for Thunderbirds.

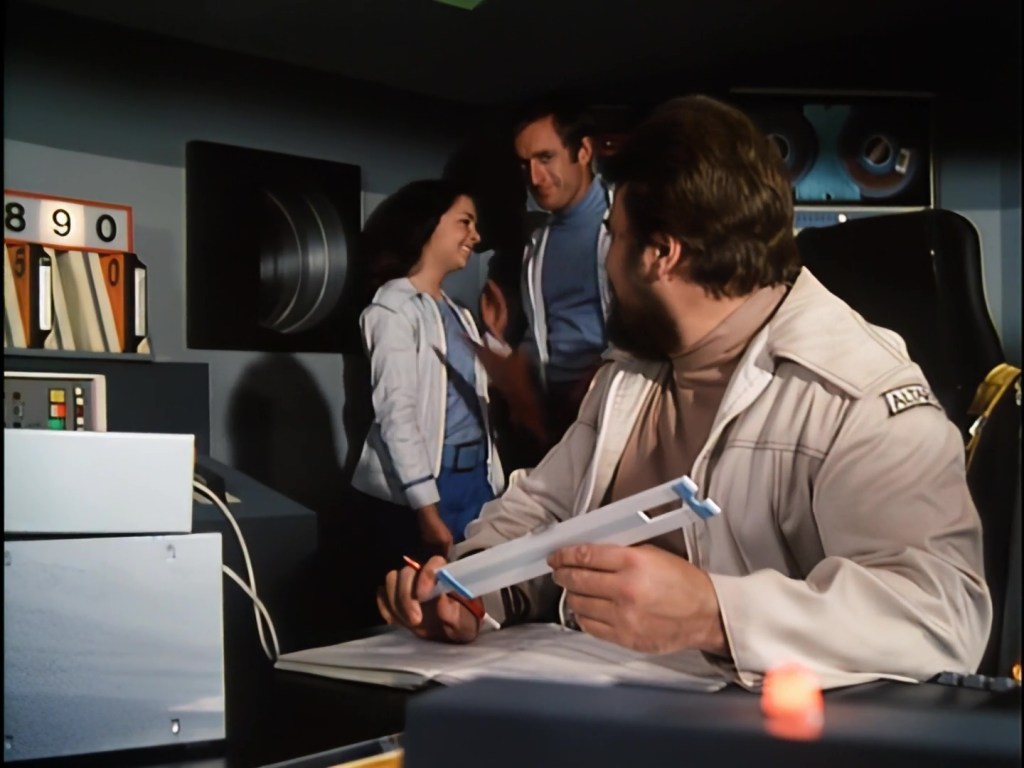

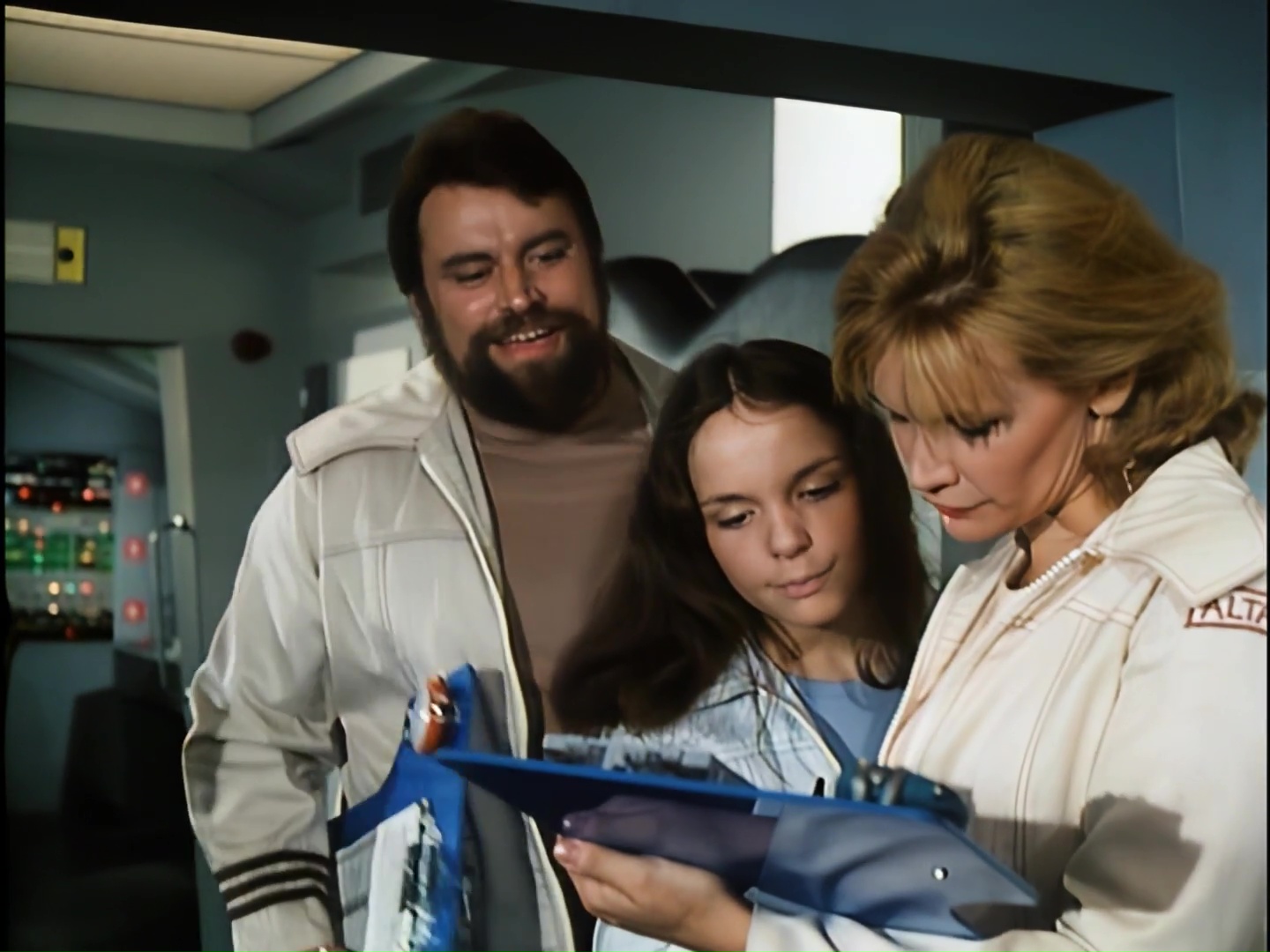

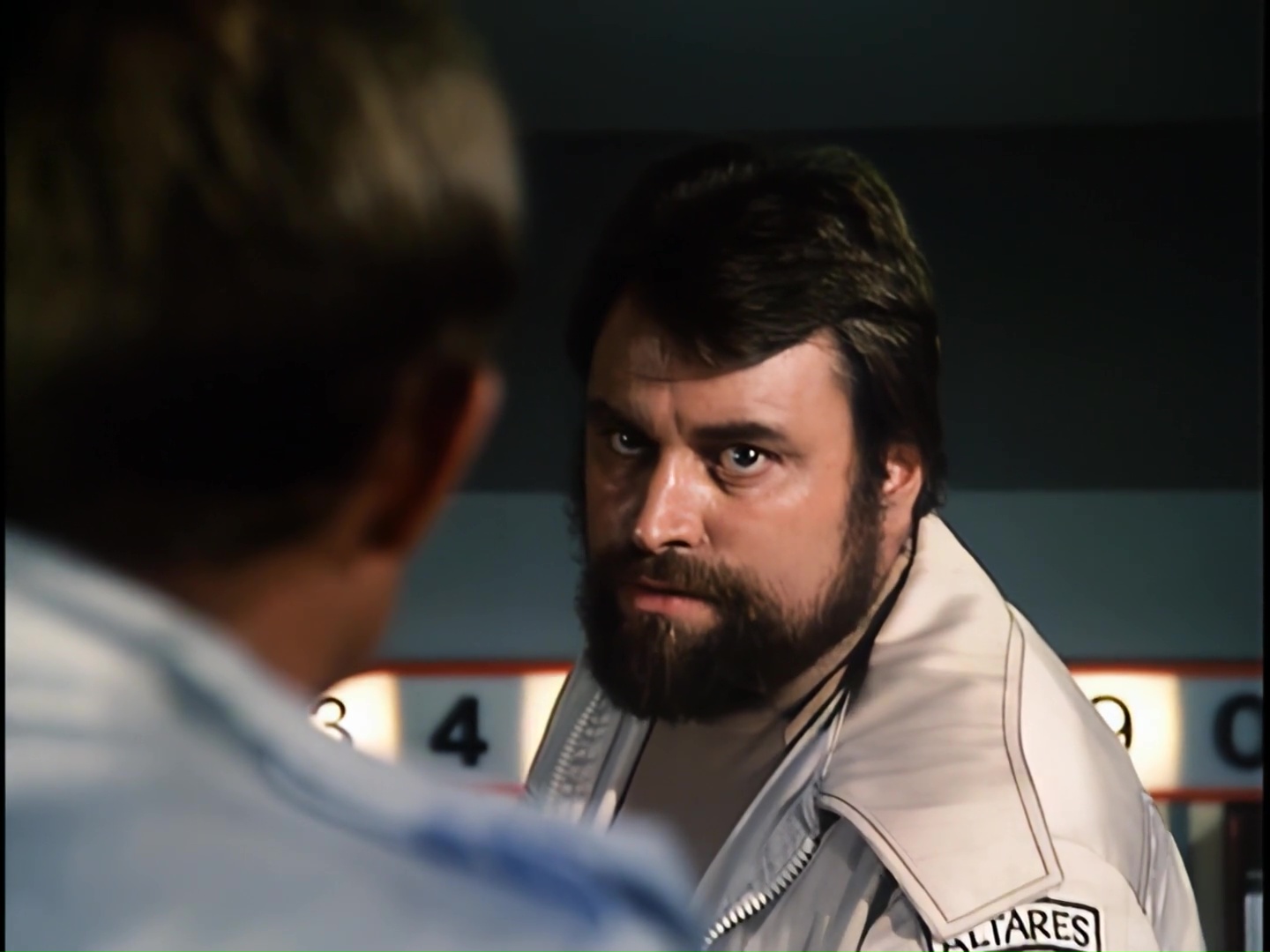

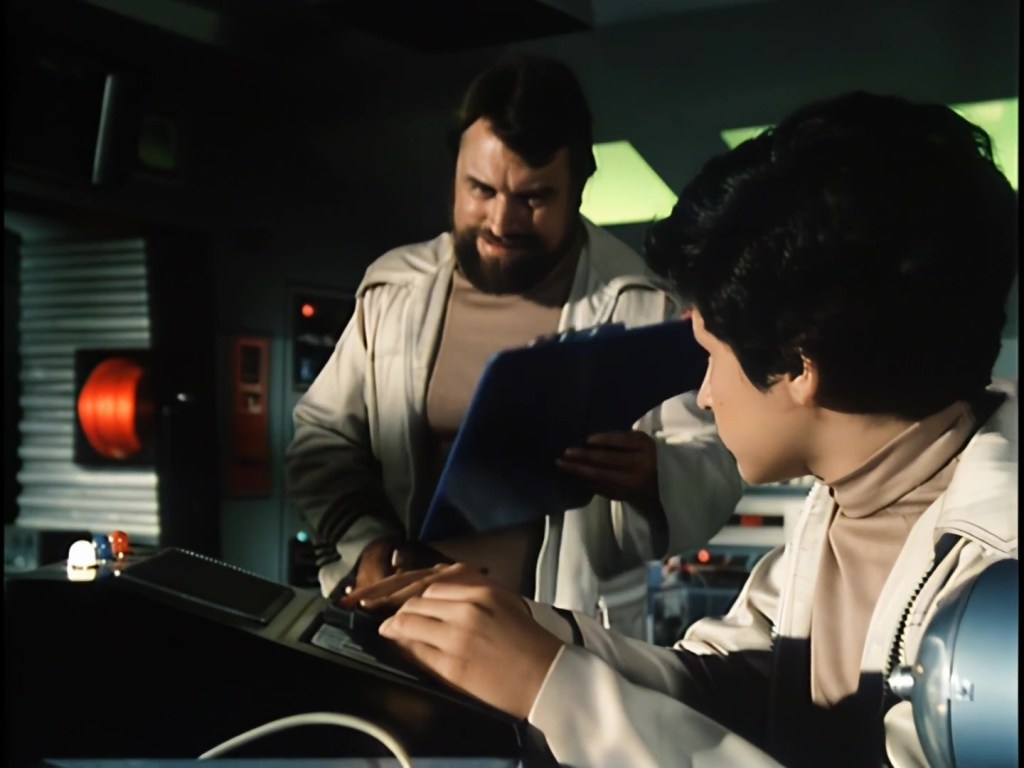

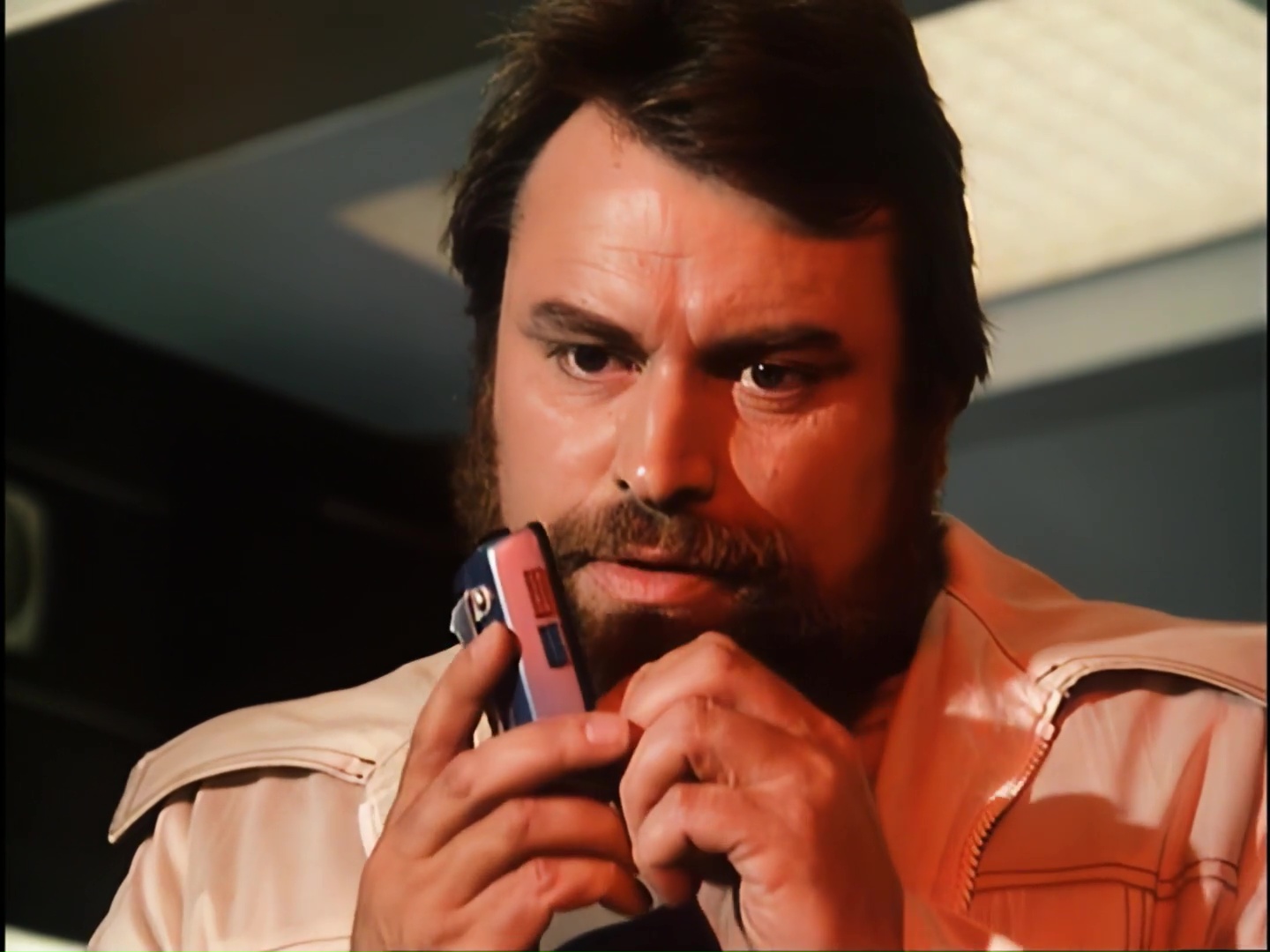

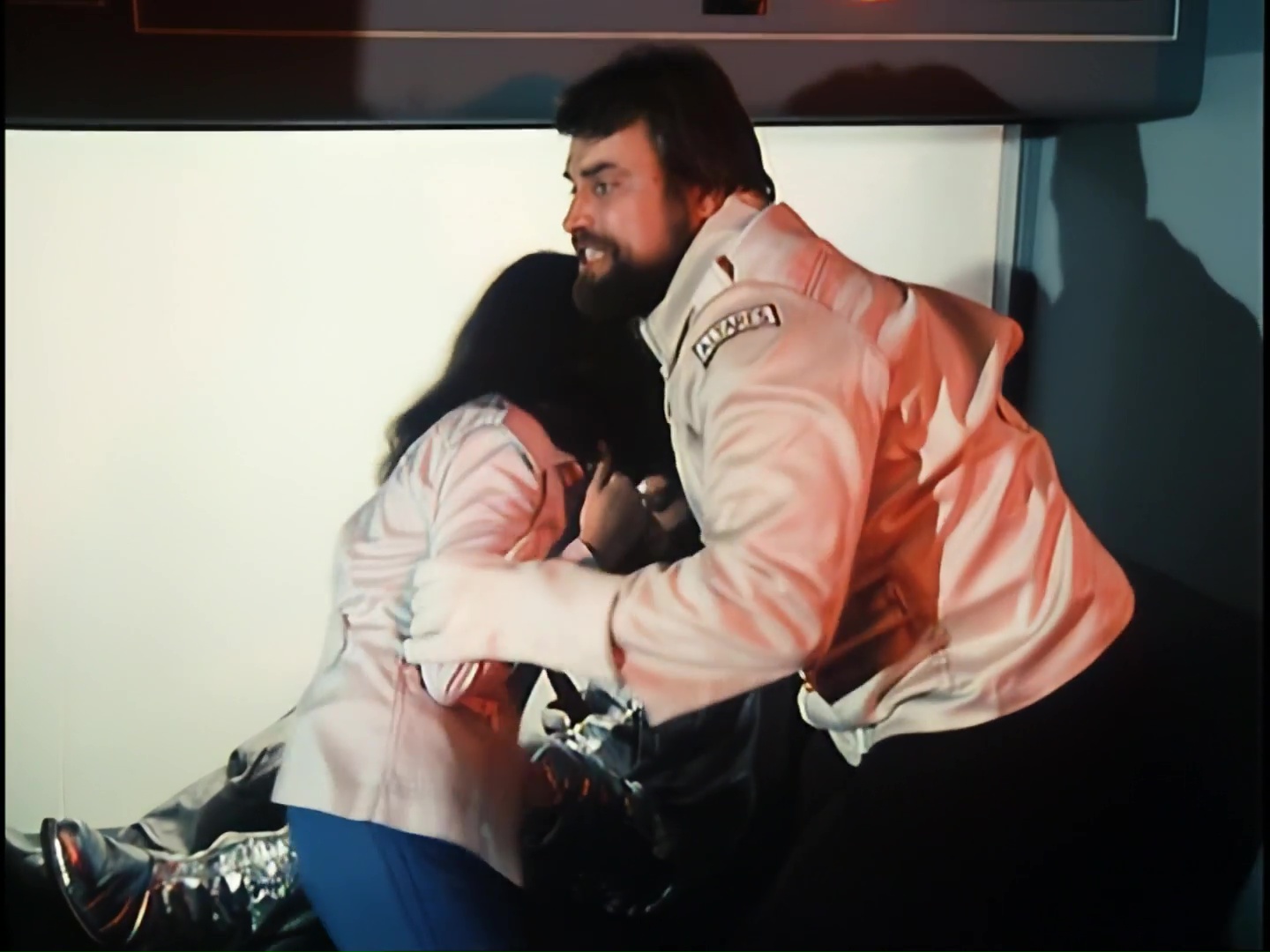

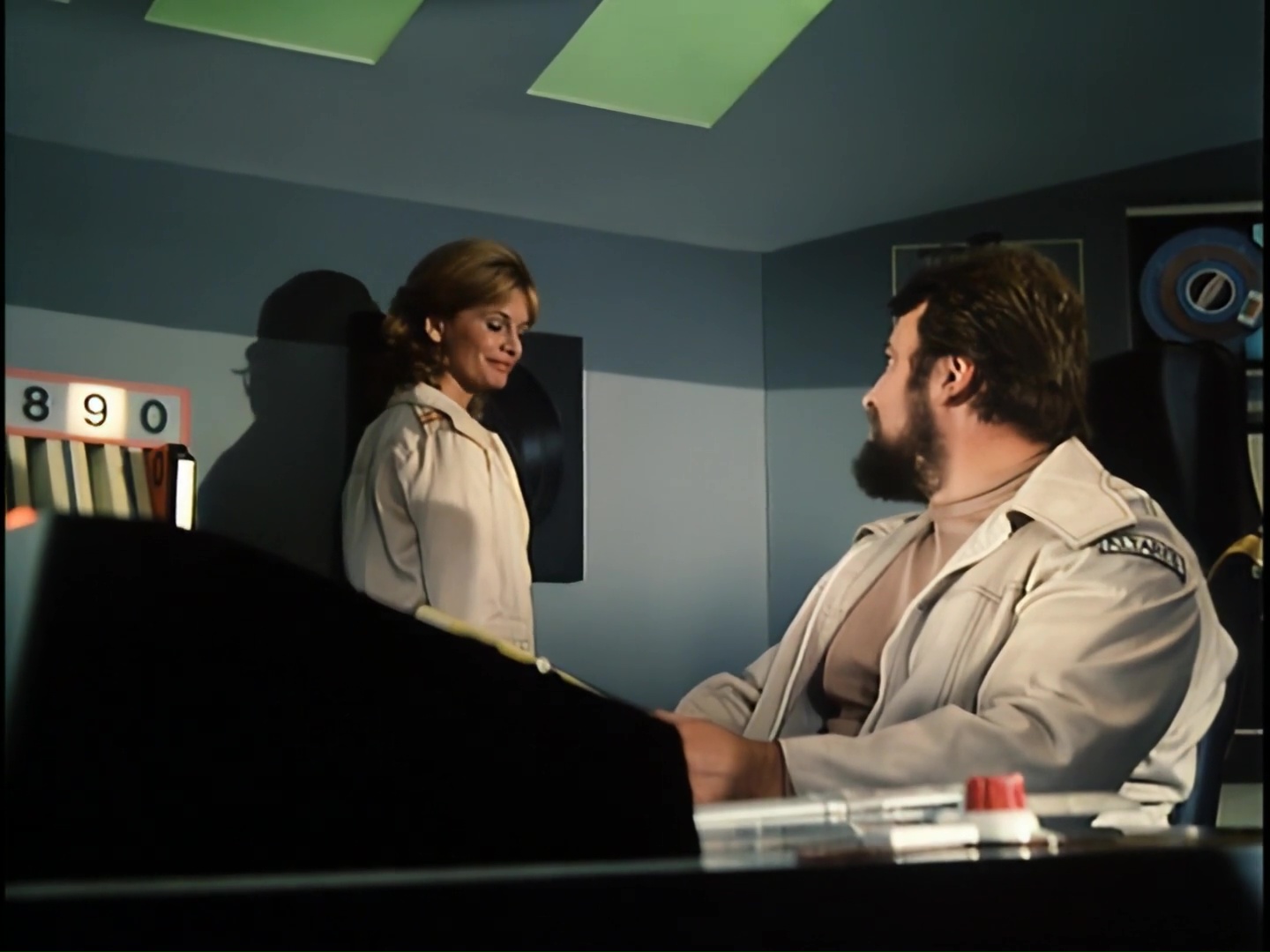

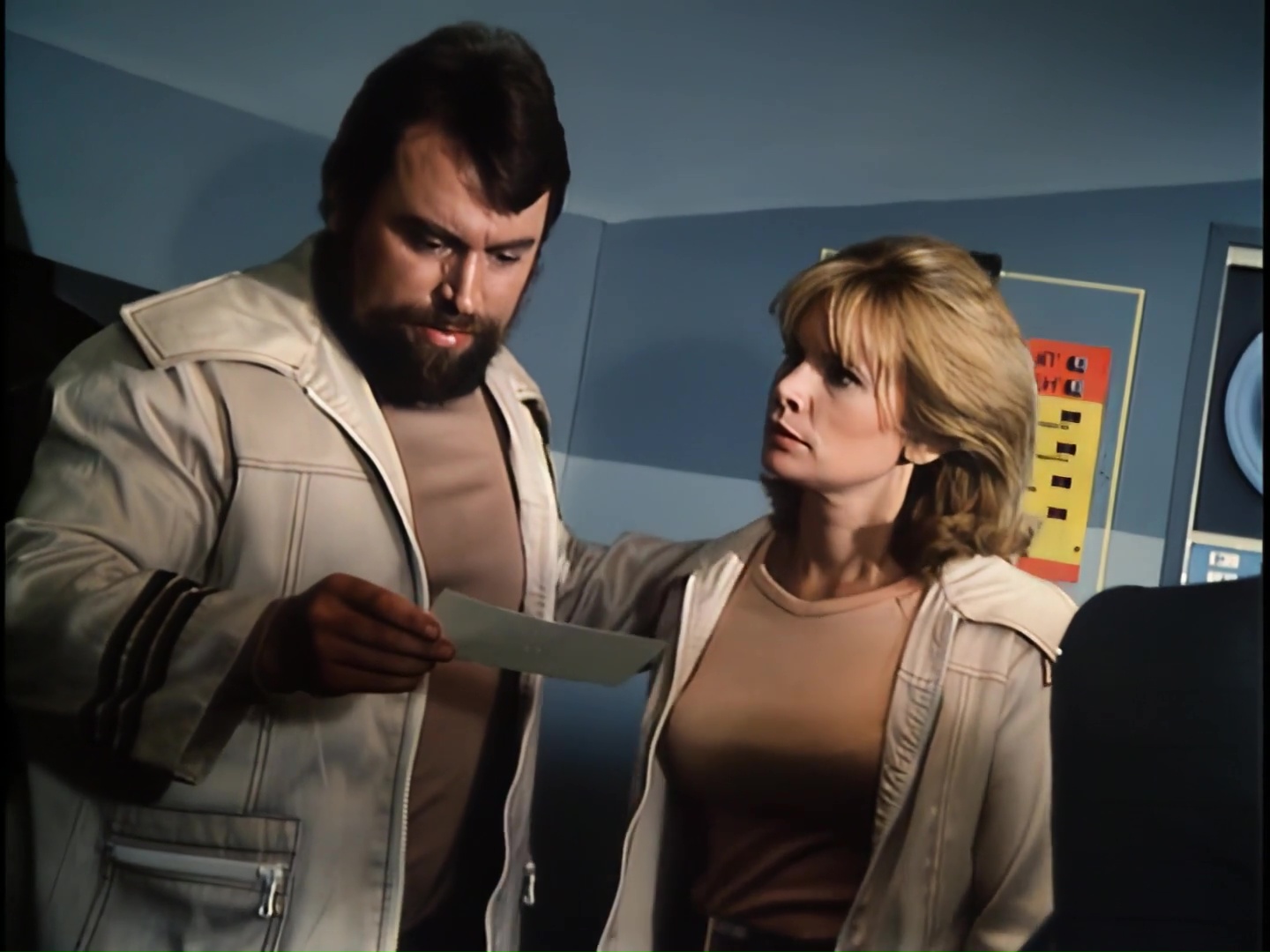

Oh look, it’s Brian Blessed. Need I say more? No, actually, I should because we need to clear something up. Nowadays, Brian Blessed is a cultural icon known for being loud, beardy, and up for an adventure. That being said, the vast majority of his acting credits actually make great use of his capacity for subtlety and great intelligence, and the part of Dr Tom Bowen in The Day After Tomorrow is no exception. Blessed also appeared as a scientist in the Space: 1999 Year One episode, Death’s Other Dominion, and subsequently in the Year Two episode, The Metamorph as a slightly more alien scientist.

Like Nick Tate, he does a wonderful job in The Day After Tomorrow of playing a fatherly and commanding role full of charisma. While the character of Harry is more of an action man, Tom is the chief scientist and the brains of the outfit. However, there’s no conflict between the two approaches. Tom and Harry are besties who seem to love working together.

Brian Blessed has always been a great ambassador for Gerry Anderson’s work and The Day After Tomorrow in particular because it so beautifully reflects his own desire to explore the infinite possibilities the universe has to offer. In the Memories of Infinity documentary on the Blu-ray, many of Brian’s thoughtful reflections on the film relate to the lessons it teaches us about why future generations should guide the way, and how humanity should respect the vastness of space as an extension of our own collective home.

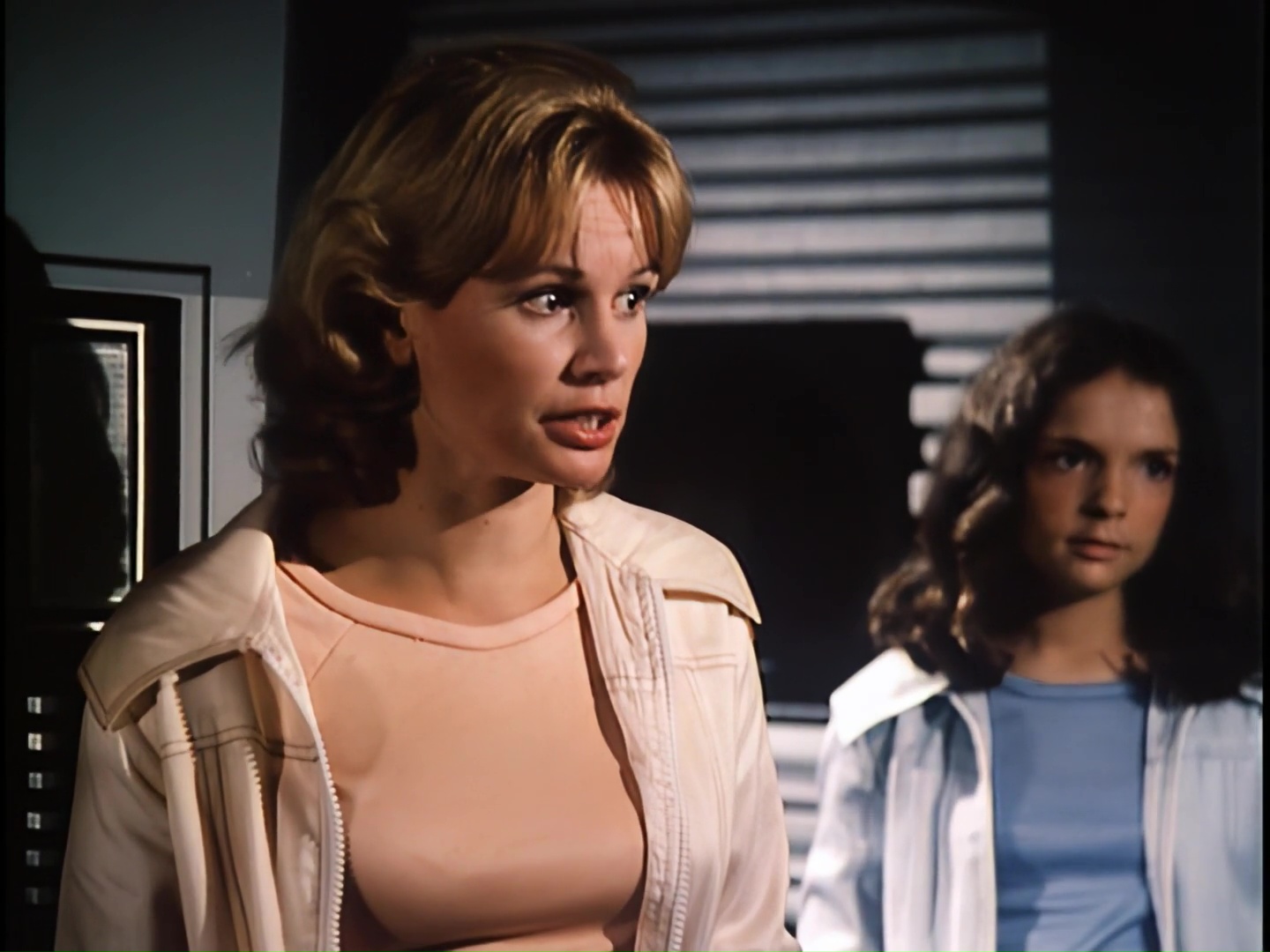

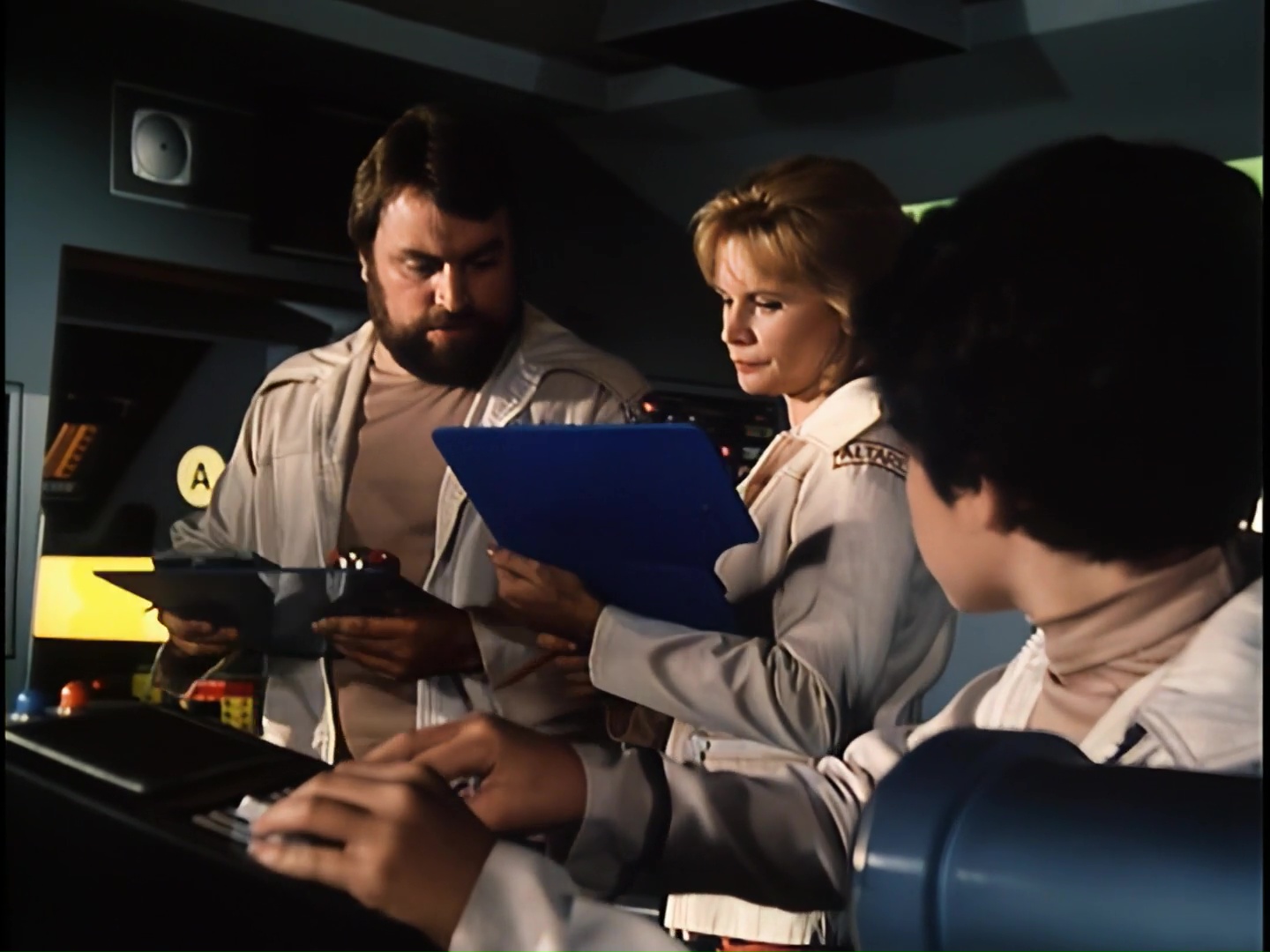

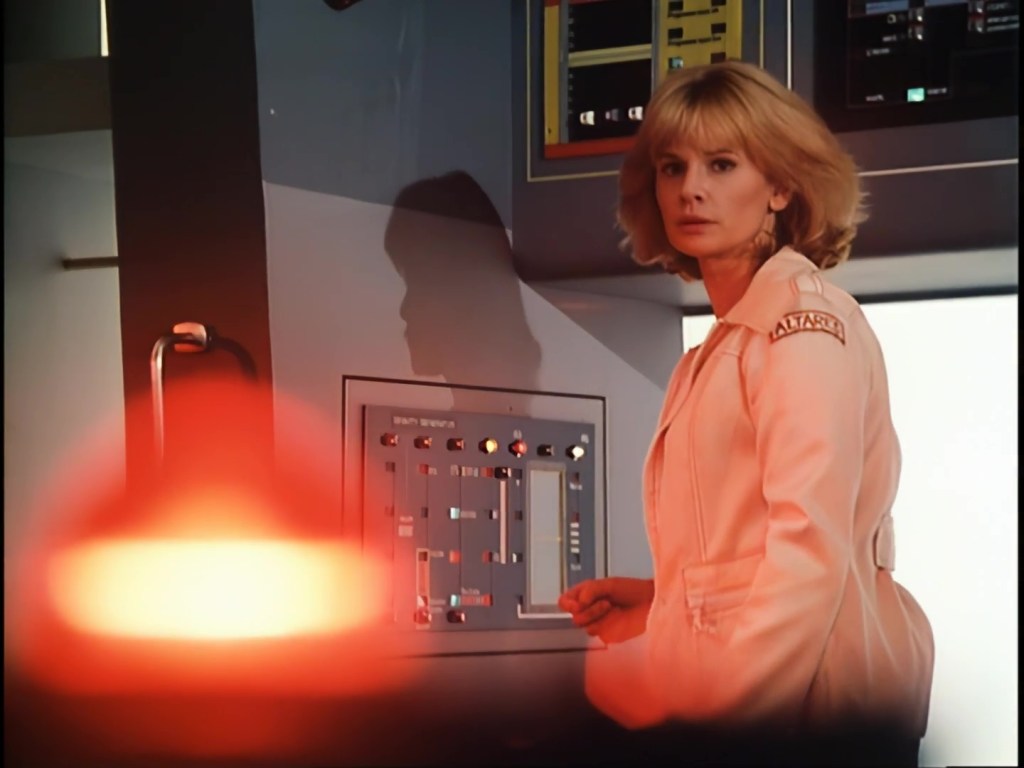

The pre-flight checks continue and working away at the back of the cabin is Dr Anna Bowen, played by Joanna Dunham. Again, Dunham had previously appeared in the Space: 1999 episode, Missing Link in additon to many other film, television and theatre roles.

Although Dunham is well-cast for the role of Anna, the character is probably the least interesting of the bunch on paper. While the children’s roles are convincingly translated into roles aboard the ship with a few sparks of conflict, and the two fathers have their positions firmly established as the two commanders handling different aspects of the mission, Anna being the sole mother/wife figure aboard means we don’t have anyone to compare her to when analysing how she adapts to the new working enviornment.

By including complete family units in The Day After Tomorrow, Anderson and Byrne are highlighting that everyone, no matter their age or gender has something to contribute to the endeavour of space exploration. Unfortunately, they don’t seem to have spotlighted Anna’s contribution quite as thoroughly as the other characters, and resort to giving her simple exposition or damsel-in-distress business so she has something to do in the story. Production photographs indicate that a scene was filmed between Anna and her son, David, in which they chat while she performs some kind of medical check-up. No such scene was included in the finished film but it might have given us a greater understanding of Anna’s character and her relationship with David. Also, if The Day After Tomorrow had made it to being a full series, I assume we would have seen more of the character’s depth and Joanna Dunham’s acting range.

As well as getting to see the families working together on the checks, we’re also getting to know the layout of Altares’ interior where most of the film’s action unfolds. Because Keith Wilson was working on Star Maidens in between seasons of Space: 1999, Anderson’s original Supermarionation art director and long-time business partner Reg Hill was appointed as Production Designer on The Day After Tomorrow. Reg Hill repurposed many of Keith Wilson’s Space: 1999 sets on the film to save money. The metallic door to the photon drive chamber was seen in the Year One episode, Force Of Life, while the rest of the interior uses Dragon’s Domain‘s Ultra Probe cabin as its basis, and the pilot station from Voyager’s Return. So, that really is the vast majority of the sets we see in the film coming from Space: 1999. Very cheap and cheerful. It works, but it does mean the Altares feels a bit less special than perhaps it ought to. It also means that the Altares doesn’t feel particularly homely considering two families are going to be spending a long, long time flying around in it.

Jane confirms that all checks are completed and puts the clipboard away. Considering how many buttons and levers she has available to press, it amuses me that the production team just decided to give Katharine Levy an old-fashioned clipboard to work with on this futuristic spaceship.

Just be distracted by this lovely model shot for a moment so you don’t notice how bizarrely Don Fellowes pronounces the word “telemetry.”

Now, you might think that video screen looks suspiciously like Don Fellowes standing behind a window and… well… yeah, it is. Unlike Space: 1999‘s impressive uptake of revolutionary tiny little TV monitors that allowed the cast to chat back and forth with each other over the airwaves for real, The Day After Tomorrow has employed a more rudimentary approach. The effect does work so long as you don’t stop and stare at it for too long. When paused, it does just look like Don Fellowes is trapped in a little box behind glass inside the Altares’ control panel. Presumably installing an actual monitor in the console was considered too costly or time-consuming for the purpose of a few very brief messages from Commander Jim throughout the film.

Since Fellowes’ shots in this conversation would have been separate inserts, it’s safe to assume the cast aren’t actually looking at anything in particular here. Nick Tate’s experience getting very little back when acting in Space: 1999 has clearly paid off as he appears totally at ease with the pretend conversation. Joanna Dunham maybe not so much, but that could also be an acting choice since the character could be nervous about the impending blast-off, or finds discussing the future death of a close friend a bit uncomfortable. The dialogue feels just a little bit clunky and forced so as to get across the effects of time dialation but then again, it can’t have been easy for Johnny Byrne to write naturalistic dialogue surrounding any of Einstein’s work. When it comes to my own naturalistic dialogue, Einstein isn’t someone I just happen to bring up in conversation very often… a fact I’m sure you’ll all be relieved to hear.

Katharine Levy plays the quiet nervousness of the situation superbly. The character of Jane is an excellent example of an audience surrogate. Instead of asking too many annoying questions or getting herself into trouble, she just quietly observes. Then, her actions and responses always come from a place of emotional intelligence, rather than scientific, so that the audience at home has a point of reference for how they themselves are supposed to be feeling. In that way, Jane is the central character of The Day After Tomorrow. I think it’s very refreshing for a sci-fi story of this nature and period to be told from the perspective of a young woman. Had The Day After Tomorrow run to a full series, we might have been considering the character of Jane Masters in the same regard as Princess Leia or Sarah Jane Smith.

Jim says his goodbyes and there’s a feeling that this is very definitely it. Sure, we’ve had all the technobabble and pre-flight checks to indicate we’re about to set off, but this is the very human indication that things are really about to kick off.

The countdown gets started and the crew strap themselves in. Lots of nervous smiles to reassure each other, and us, that this is scary but exciting stuff. The connection with the viewers at home is just so effortless. These are human actors doing very human acting. That sounds so obvious, but it’s a common criticism that the first season of Space: 1999 in particular feels too sterile and difficult to emotionally engage with. But all five of the main cast here have something about them which you can connect with. There are little touches to their performances which make them feel like people first and space heroes second. That’s a very important factor when considering the scientific topics of the film are so complex and impenetrable.

Anna is seated far away from the rest of her family at the back of the ship. There could be something to read into here, since her son, David, is seated further forward and next to his father. We’ll see later that David is characterised as the more grown-up and professional of the two children and it’s possible that the physical and emotional separation from his mother is used to convey that part of his personality. It also wouldn’t be the first time that a mother character has been sidelined in an Anderson production, but that’s a pretty cheap psychological assessment so I won’t go there.

David faces forward, totally cool and collected as the countdown continues. Tom observes him with a look which I read as both pride and concern. Tom’s not thinking about the mission right now. He’s thinking about his son. The boy bravely following in his father’s footsteps without any hesitation or missteps. Will he be up to the challenge? Is David giving up his childhood a little too willingly? There’s a lot to unpack here if you’re into studying the evolution of family dynamics over the course of the 20th century.

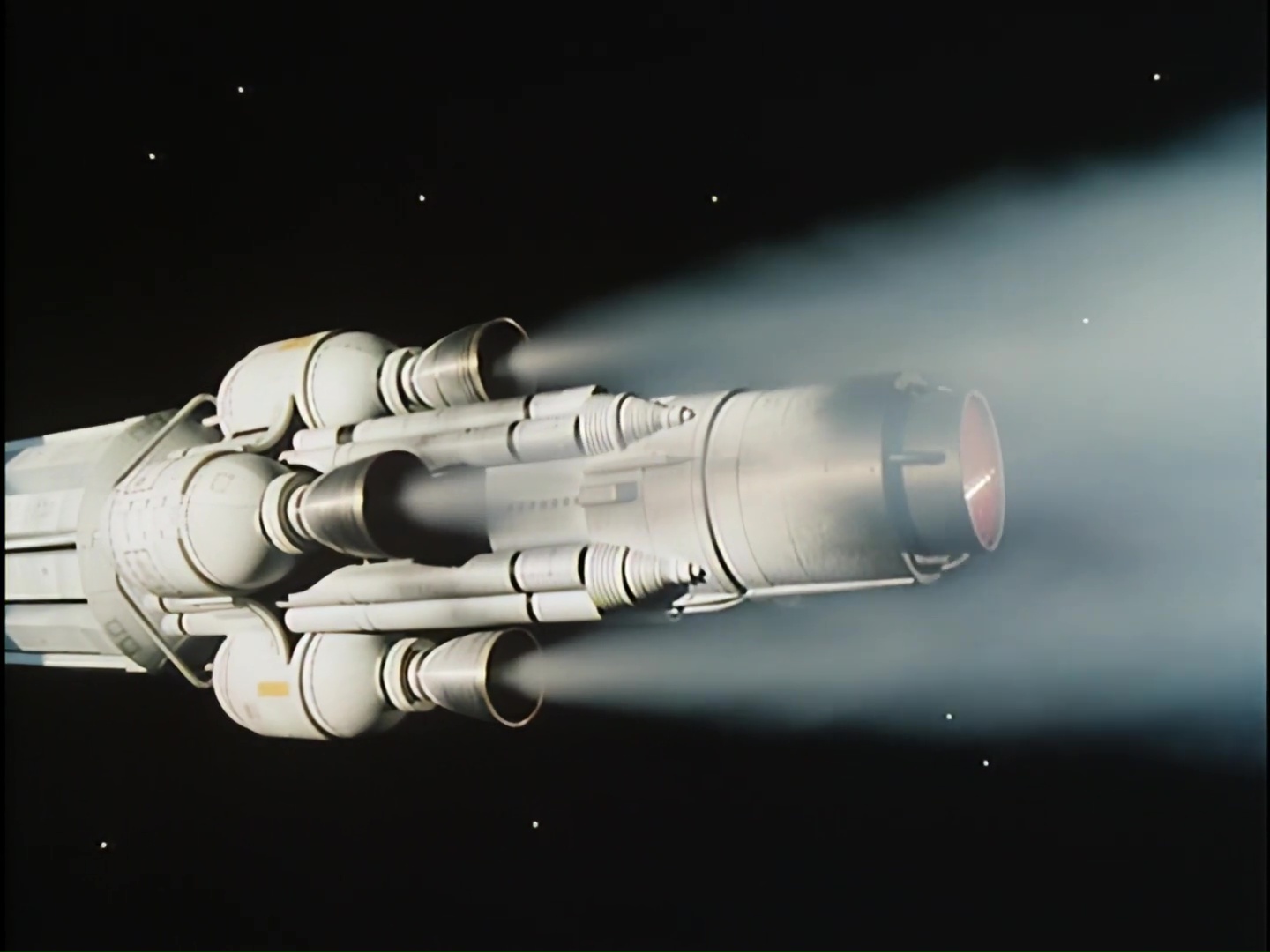

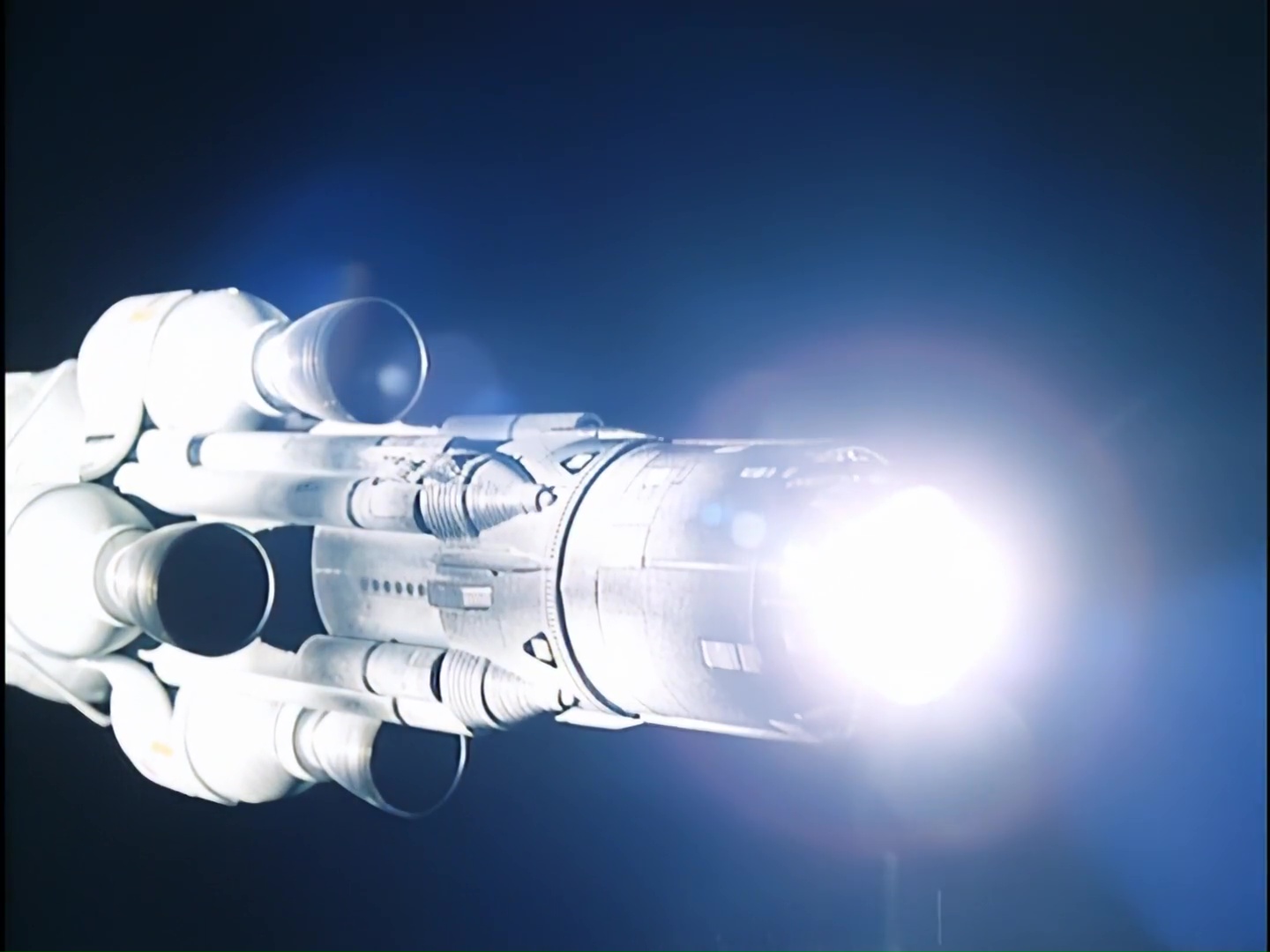

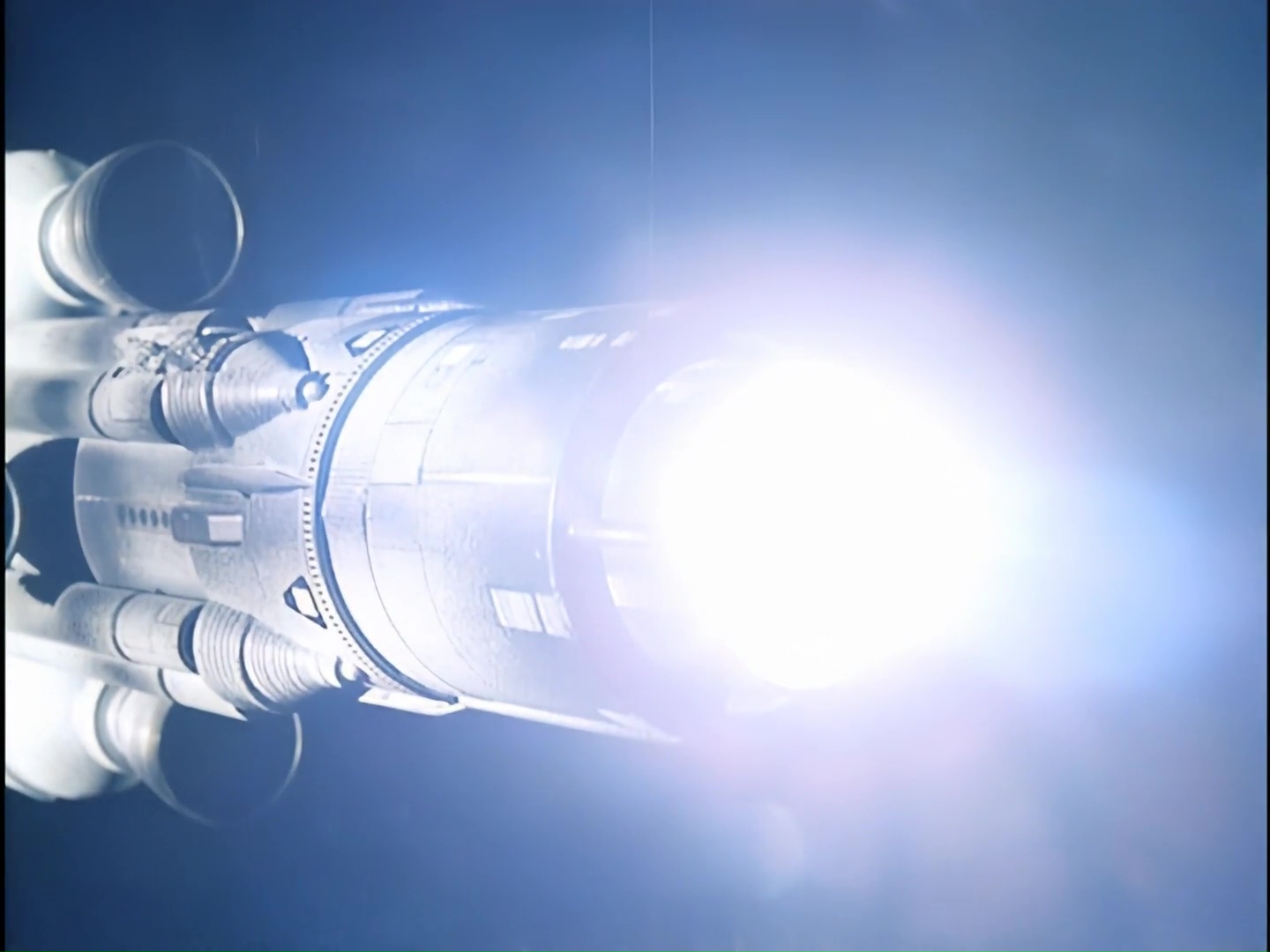

The Altares begins to slowly ascend from its little podium atop Space Station Delta. The incidental music from Derek Wadsworth and Steve Coe is tremendous as the tension builds towards launch. If you think the thrusters on Altares look suspiciously like the back-end of an Eagle you’re definitely starting to catch on.

In the final seconds of the countdown, the camera focusses in on Harry, therefore positioning him as the most important person in charge of the mission. He’s responsible for guiding the ship on its voyage. It’s a camera movement that says “this guy has the most responsibility, so all you viewers at home had better listen to what he has to say.”

But it’s Jane, under her father’s command, who pushes the button to set them off on their journey. A symbol of the younger generation being given a helping hand to take control of their own destiny, perhaps?

I know I’m reading a lot into this but hear me out. Think about the seating arrangement on a traditional, miserable, 1970s family car journey. They’re driving through the rain to a run-down holiday camp in Dorset. Dad’s driving in the front, Mum’s next to him reading a map, and 2.4 children are on the backseat causing chaos and not wanting to be there. Quite a contrast to what we have going on aboard the Altares. Father and daughter are up front, sharing the driving responsibilities. Father and son are close behind them to navigate, also sharing equal responsibilities. Mother sits alone, far at the back, her role in all this not yet defined. It’s certainly a progressive picture in some ways, but quite unflattering in others.

Whoosh! And they’re off! Sort of. It’s a little bit of an anti-climax. The thrusters produce beautiful plumes of freon gas for a short while but then cut off shortly after. Not exactly the buckets of exhaust flame you might see pouring out the back of Fireball XL5. Of course, space travel is being portrayed as realistically as possible in this film, so really the Altares only needs a relatively tiny blast of propulsion to get it moving away from Delta. Altares cruises past the Moon just to annoy anyone who believes in the remote possibility that The Day After Tomorrow is set at the same time or in the same universe as Space: 1999.

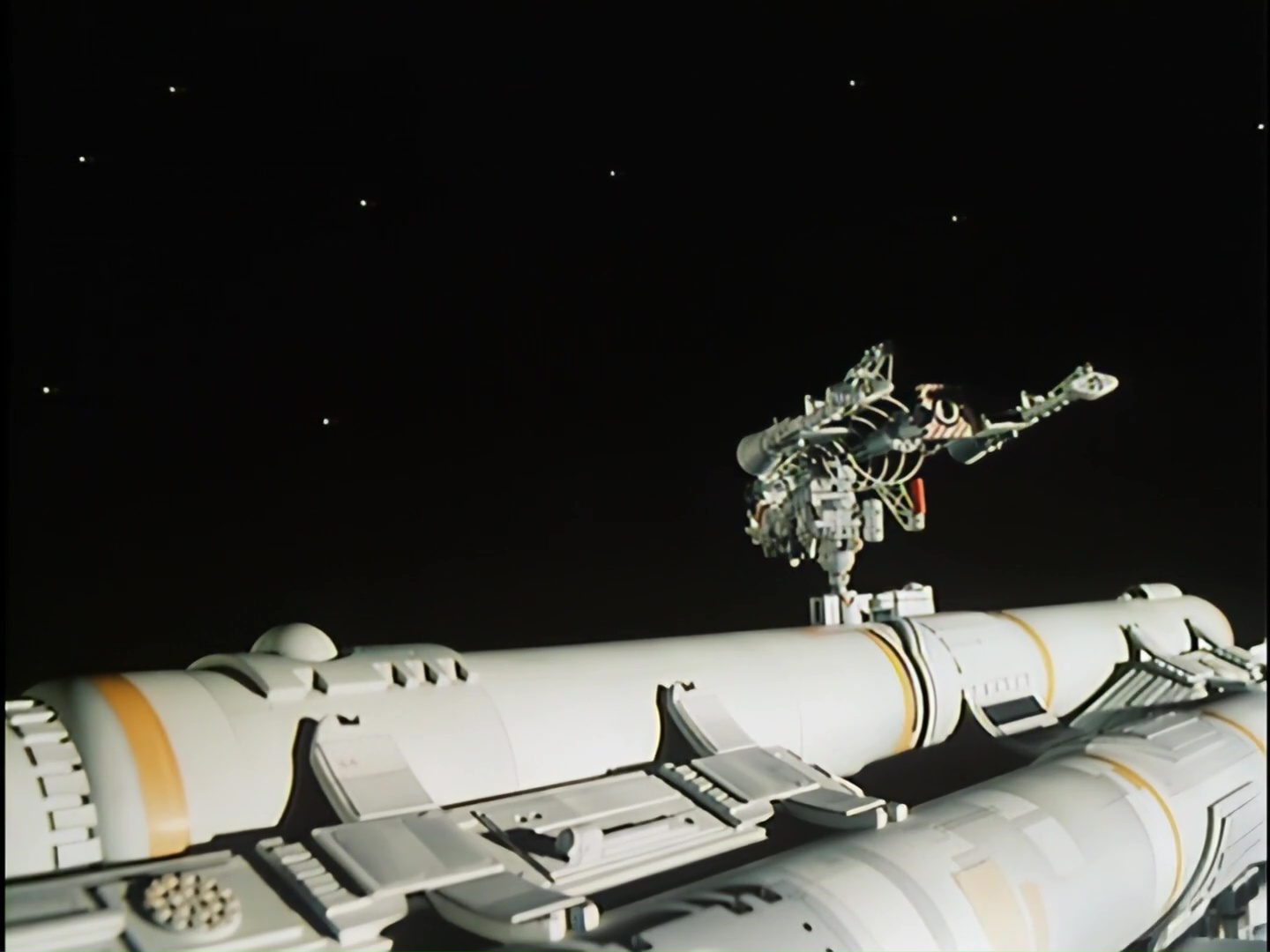

With the Altares on course, Jane is instructed to point the particle scoop to 317. The fancy-looking antenna actually started life as a Moonbase Alpha gravity tower. This particle scoop is presumably intended for gathering fuel particles for the ship’s propulsion systems. Either that or it’s for picking up extra sports channels.

Now it’s time to get your photon on. Big scary control knob. Big scary light at the back of the ship. Big scary red flashing “radio-active” sign… bit weird to see the word “radioactive” with a hyphen in the middle but I’ll try to get over it.

Nick Tate is an absolute master of the “make-pressing-a-plastic-button-look-super-serious” acting technique.

The Bowen family are menaced by enormous flashing red lights.

Acceleration starts to happen, and Anna gets even more nervous about that flashing red light.

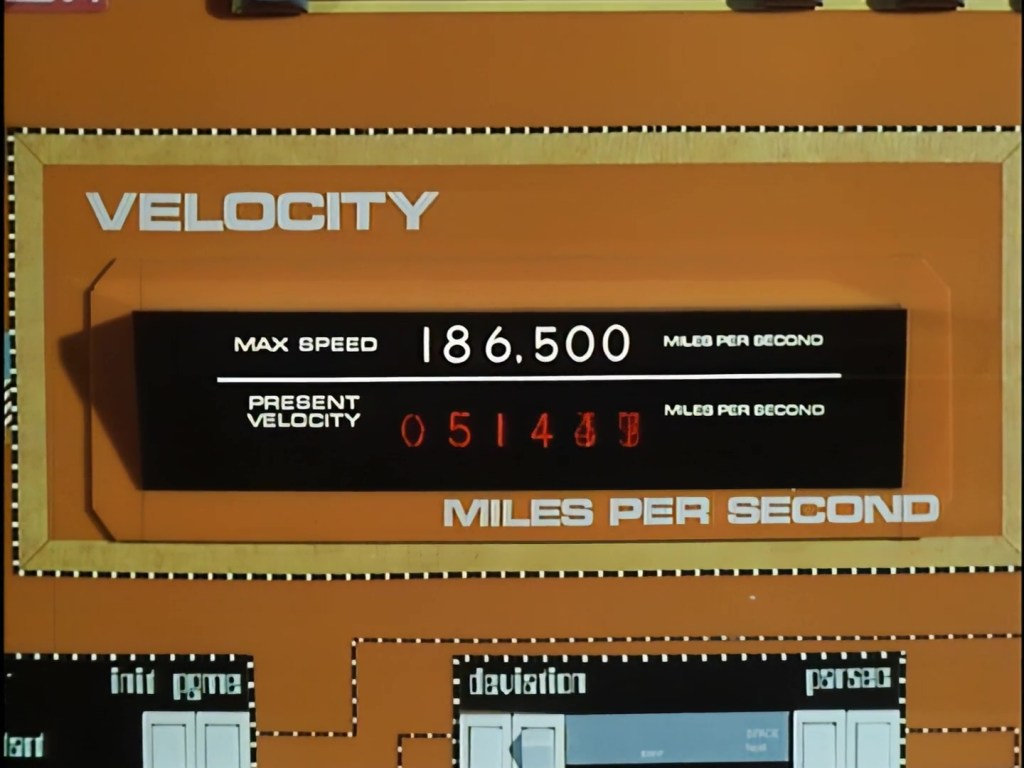

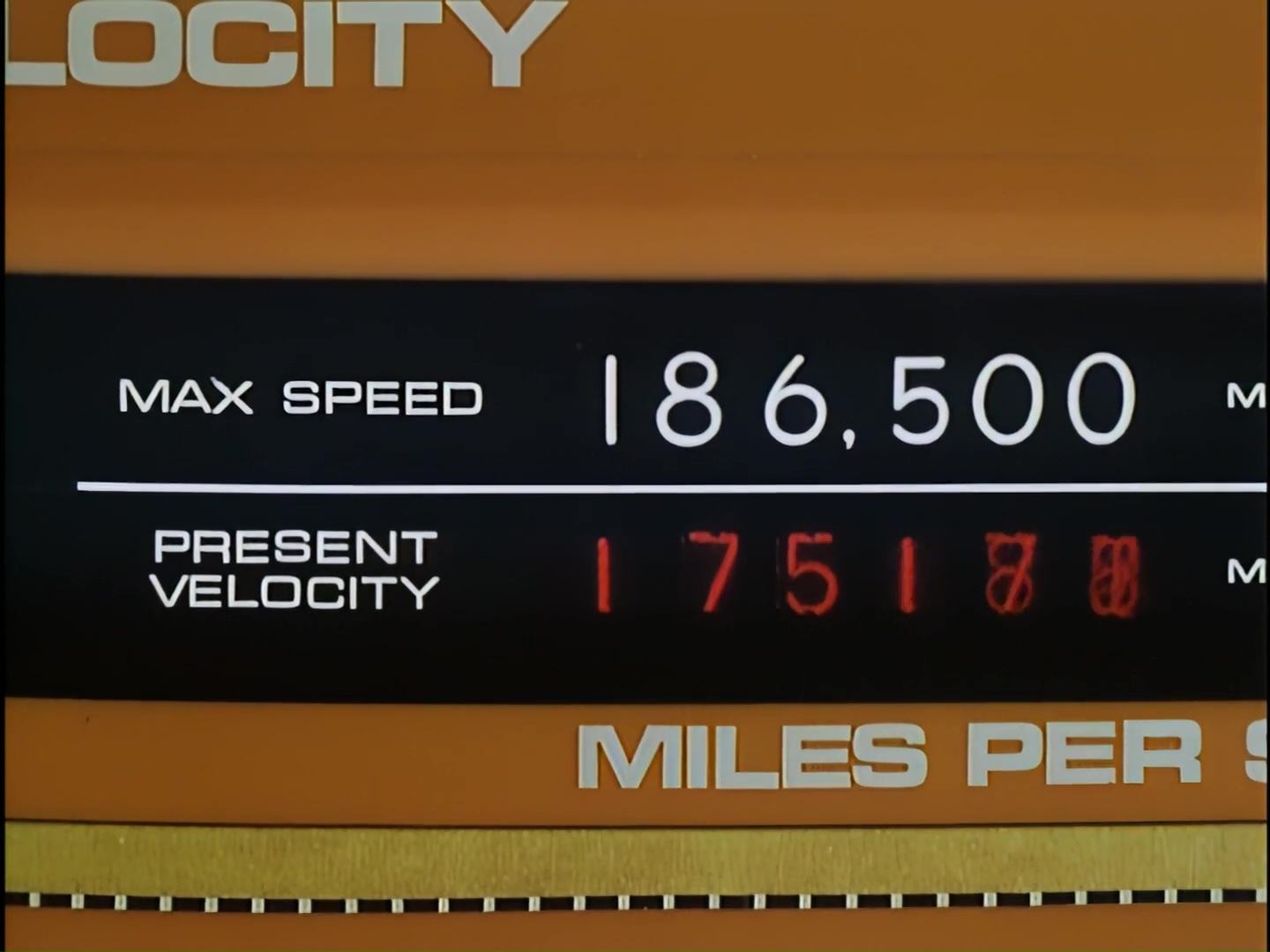

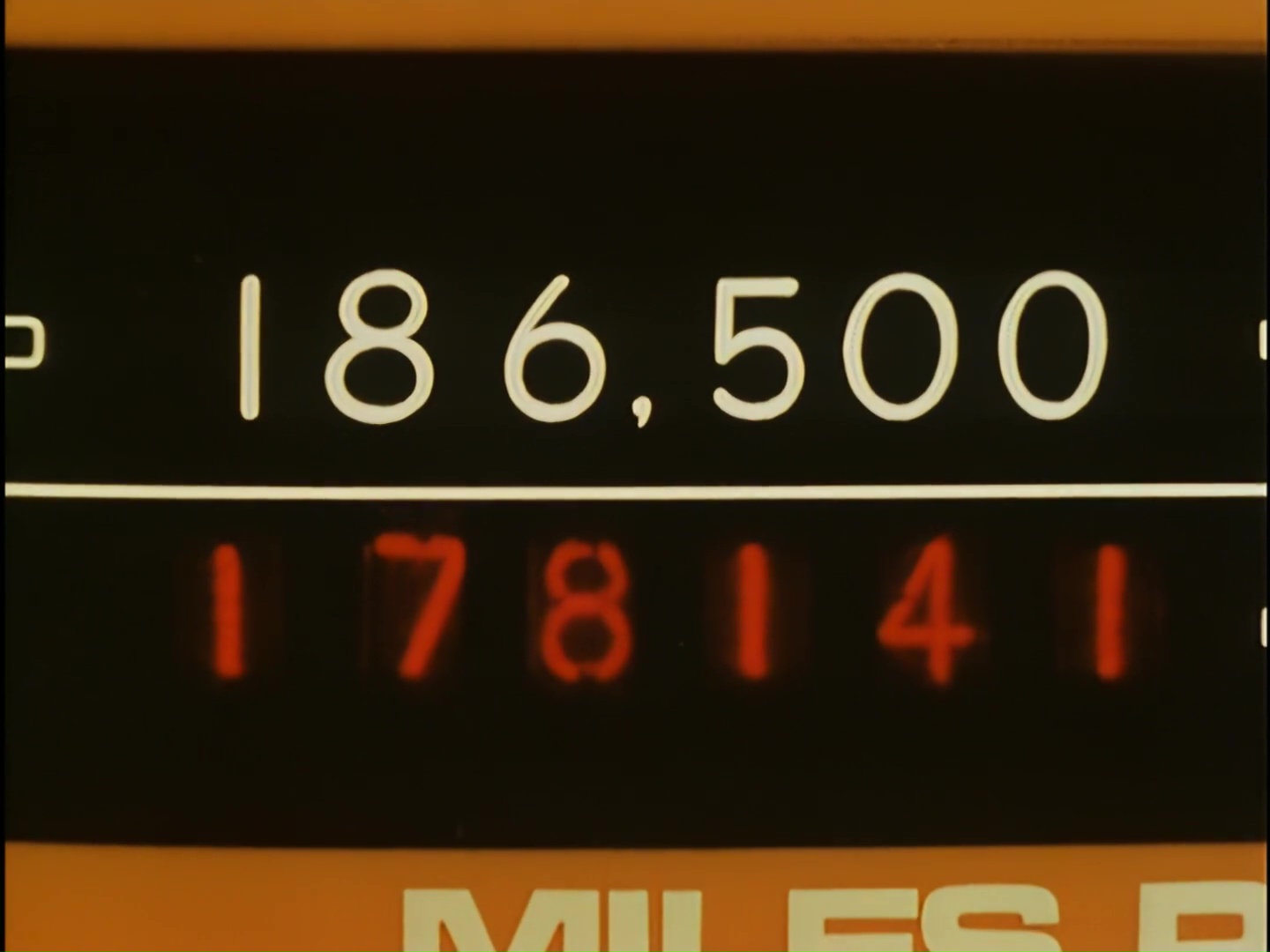

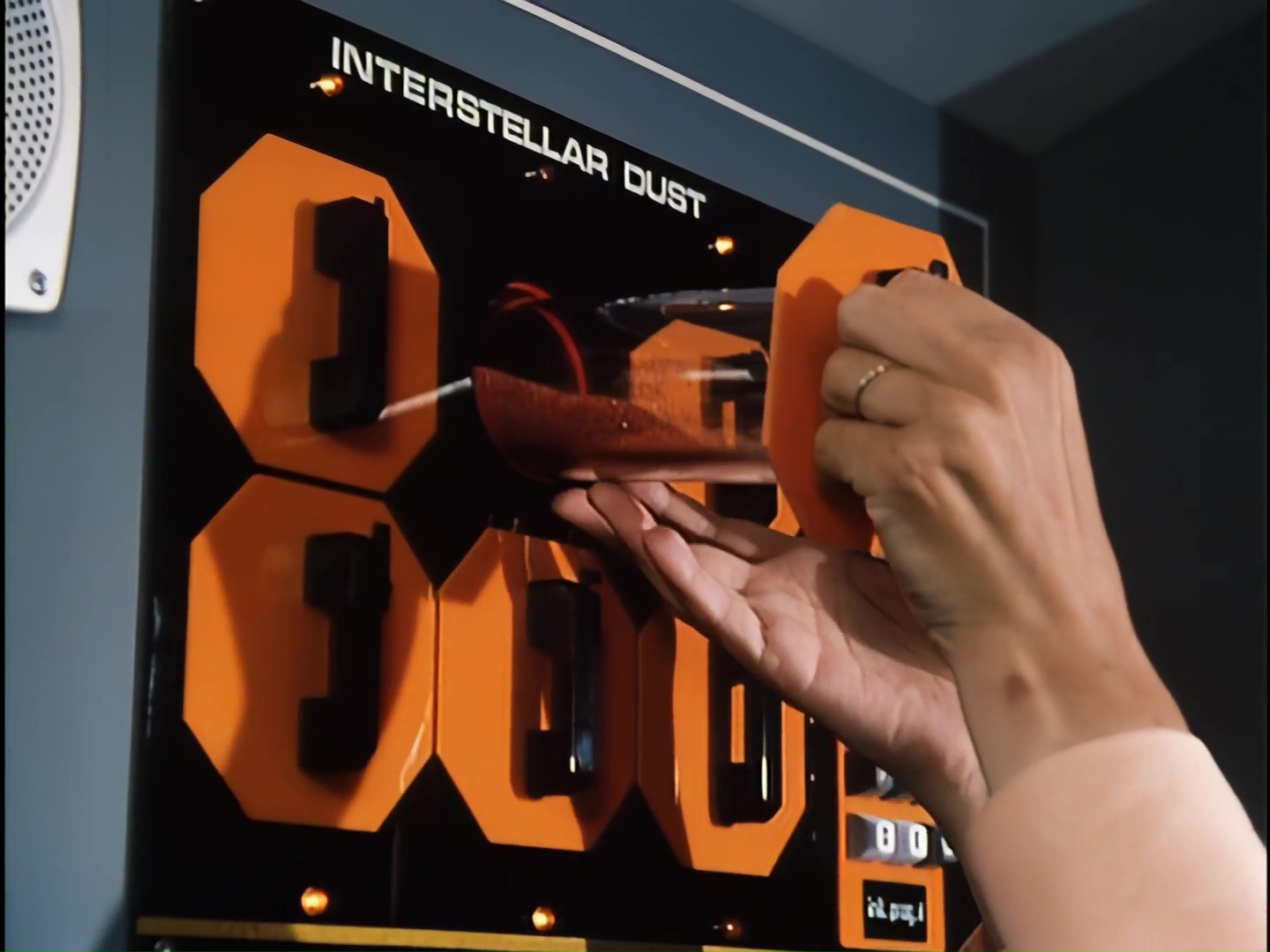

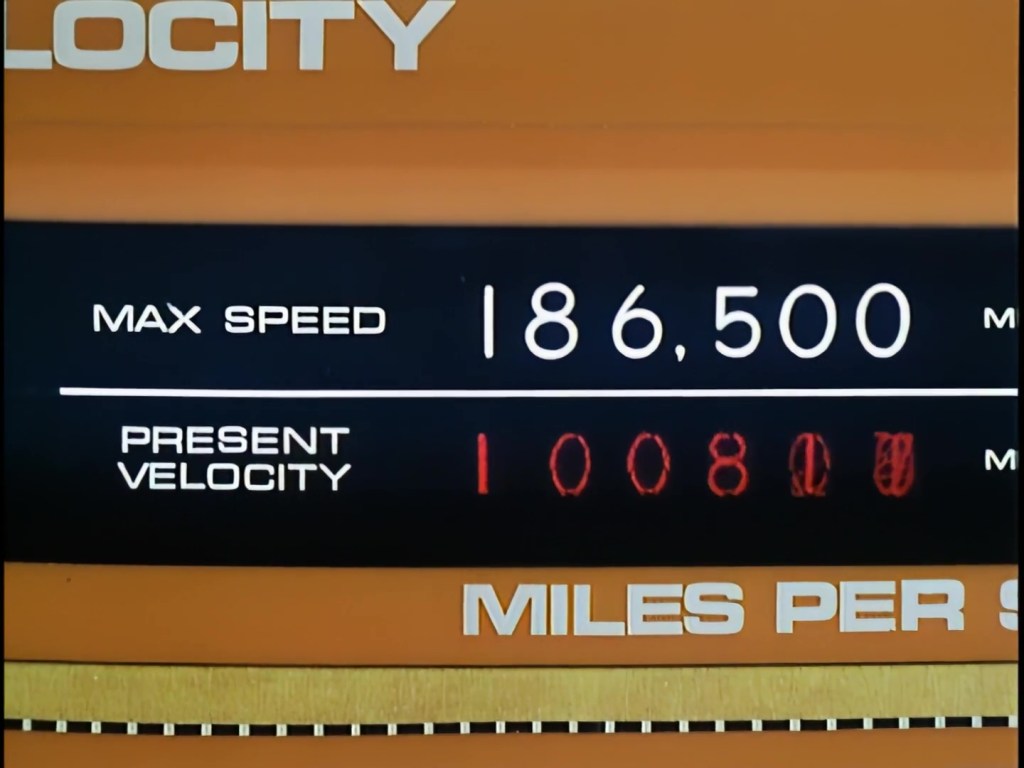

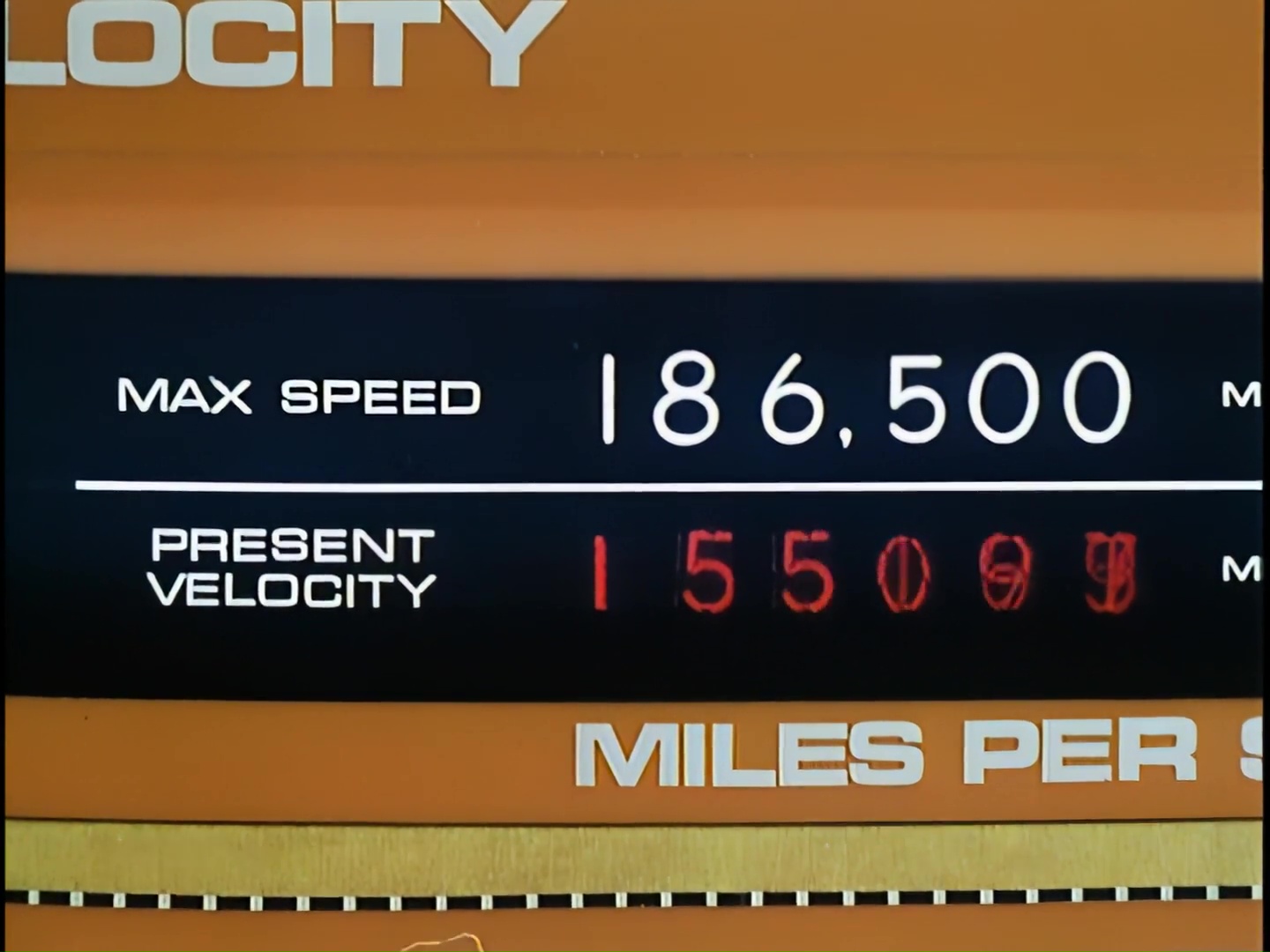

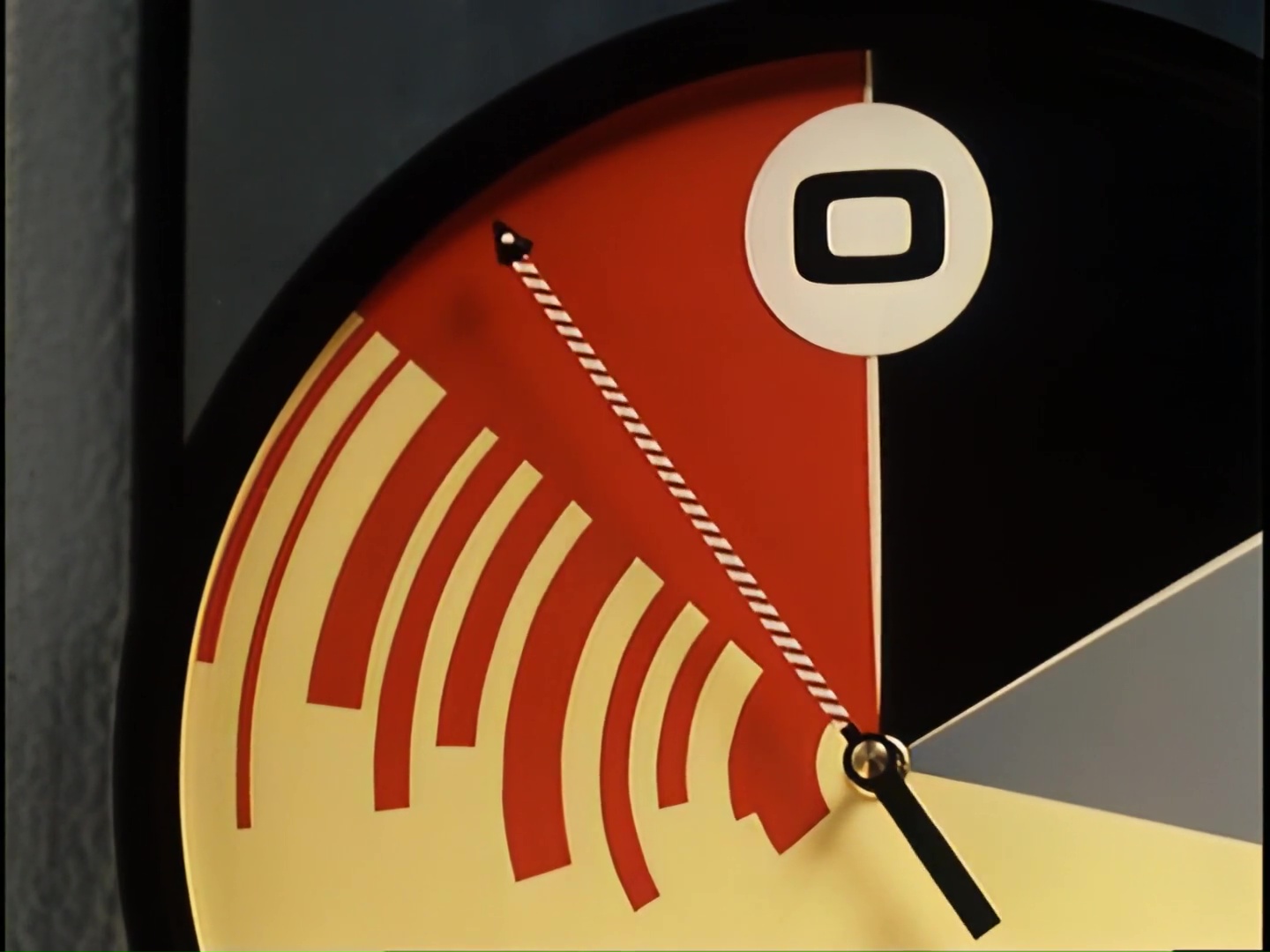

A handy sign on the wall allows the viewers at home to quantify what the visual effects simply cannot get across on-screen. The goal is to hit somewhere in the region of 186,500 miles per second (the speed of light in round numbers). As we can see, the present velocity of the ship is ticking up quite rapidly as the Altares builds speed. Quite rapidly is a bit of an understatement actually.

David is chillingingly unfazed by the big red light that seems to be bothering his parents so. He’s just taking the mind boggling g-force like a champ.

We get a lil’ bit of doppler effect happening now and Jim tries to distract the Altares crew from the extreme discomfort they’re experiencing by explaining to them that they’re into the red spectrum of the doppler shift. Thanks, Jim – there’ll be plenty of time for an astrophysics lesson later but no, you go ahead and push some science into their brains while they’re all are having their heads squeezed by g-forces like a melon being driven over by a tractor.

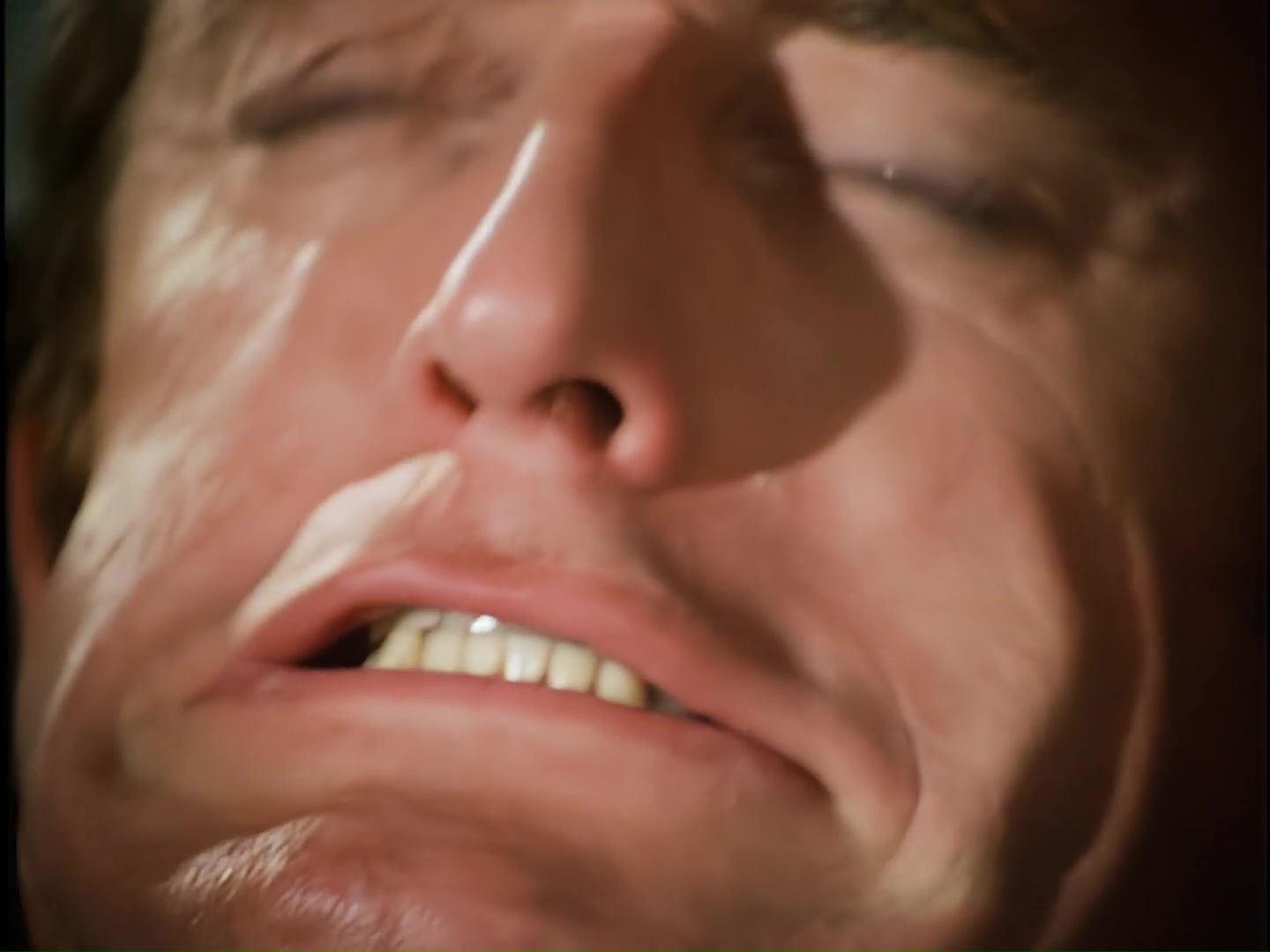

Go on then. Have a giggle at all the funny faces. Apparently having the equivalent of a leaf blower blasted in your face is just as unpleasant as it looks. Scientifically speaking, the acceleration the crew are experiencing would actually turn them into dust – less than dust probably – but that wouldn’t make for a very good film so instead we’ve got flappy skin and some minor discomfort to convey the extraordinary speed having an impact on our heroes. Brian Blessed’s floppy cheeks would, of course, serve him well in later life playing the role of Boss Nass in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.

The editor, Anderson veteran David Lane, and the special effects team do the best they can to convey the extraordinary speed of the Altares on-screen. It’s fast – very, very fast. But I don’t think the audio-visual medium of television can truly communicate what travelling close to the speed of light would actually be like. By the time you see something it’s already gone past, so you can’t possibly capture it accurately on film. Since the concepts are so abstract and thoroughly unfriendly to the senses of sight and sound, Johnny Byrne and Gerry Anderson have chosen instead to put a good amount of focus on the more human element of the story. The audience at home has no hope of connecting with the feeling of travelling at the speed of light. We can’t begin to relate to that. What we can relate to is suddenly being far, far away from home, not really knowing how we got there, and having to accept the reality of being stuck somewhere hostile.

The photon drive cuts out and thankfully we have all manner of flashing lights and wailing sirens to indicate that for us.

The crew recover from their 178,141 mile per second joy-ride pretty quickly. As the audience surrogate, it’s up to Jane to put it in terms we understand and explain to us that the experience was like being flattened. She’s able to laugh it off though. Kids watching at home will therefore feel reassured that although space travel is uncomfortable, it’s basically fine and nothing to worry about. Nevertheless, it is nice for us to have a moment to acknowledge that these are fragile, regular people flying this spaceship.

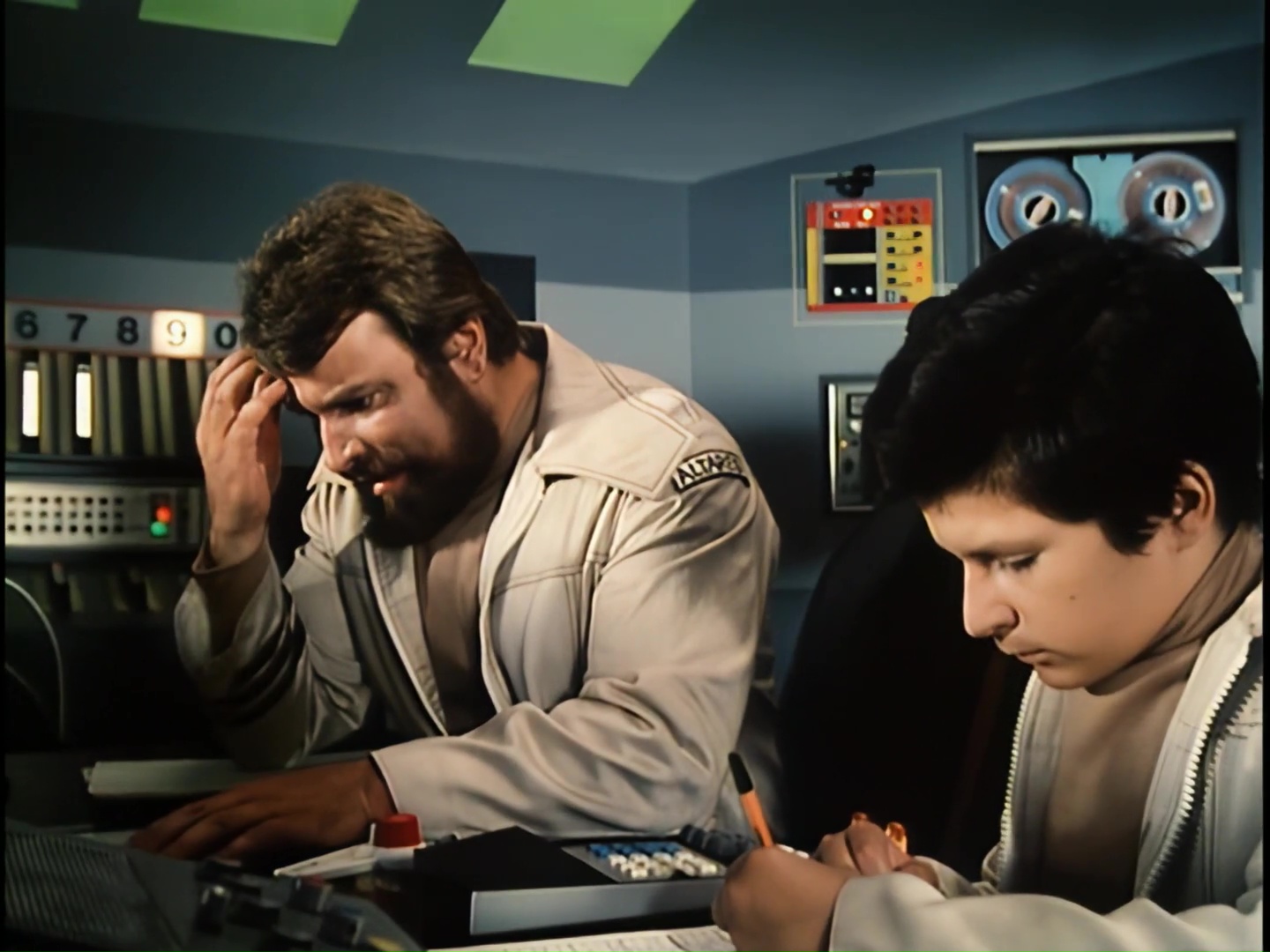

In contrast, David and Tom have gotten straight to work figuring out how to correct their navigation after an error on launch. No messy, human, “wow that was rough, Dad,” from David – just business as usual and fixing problems.

Once the pair of British boffins in the back do some sciency stuff with the computer, it’s up to the cheerful American(ish) pair up front to smile and assure the audience that we’re on our way for a lovely, jolly adventure. I know I keep banging on about this audience surrogate thing but I can’t emphasise enough how important it is in a story as theorectically complex as The Day After Tomorrow. By the way, has anyone seen Anna? Has she dozed off in her chair at the back?

Here’s a brief moment that you’ll either love or hate. Jane gazes out of the window and sees a blue planet approaching, but smarty-pants David points out that it’s actually Pluto and it’s only blue because of the doppler effect.

Jane calls out David’s smug man-splaining but he ruddy loves being the smart-arse of the group. Katharine Levy beautifully emotes the “ugh, what a harmless little nerd” sentiment before turning back to the window.

She watches Pluto go by and turn red, just as David predicted it would. Ignoring whether or not Pluto is or isn’t a valid part of the Solar System for the time being, just consider what this is supposed to symbolise. It’s Jane saying goodbye to the very furthest point that connects her with home, and she does so with some sadness, quietly and alone, while everyone else is too busy getting on with their work to particularly notice the landmark.

Katharine Levy absolutely perfectly portrays that pit-in-the-stomach apprehension that we all feel when we leave our homes once and for all. Through her, we understand that Pluto whizzing by is the emotional equivalent of seeing our childhood home in the rearview mirror for the final time. For Jane though, there’s an even more dreadful feeling at play because she didn’t even recognise Pluto in all its blueness when she first saw it. Imagine leaving home for the final time and not even knowing you were doing so until someone coldly pointed it out to you. Once again, I love how simplistically the connection between our lived reality and science fiction is made here.

Now, on the other hand, you might hate this moment because of how on-the-nose it is about educating viewers on the doppler effect. Although the exposition from David does come thick, fast, and quite unnaturalistically, it does at least achieve its aim. As the poor fool who spent his Physics GCSE exam with his head in his hands, I think it’s fair to say a more subtle, nuanced, expansive explanation of the doppler effect would have gone completely over my head. So if it has to be in there, at least it shouldn’t be confusing.

One side effectsof this approach does mean that young David comes across with the demeanour of a middle-aged science teacher. He’s quite condescending towards Jane and she knows it. People who might have been expecting David to fulfill the audience surrogate role alongside Jane will suddenly find him quite off-putting. However, the film makes it very apparent later that he’s not necessarily there to be liked. More on that later.

With the last remnants of their own solar system behind them, the crew of the Altares head into unexplored space, and the end of the first act, with a combination of cheerful optimism, and slight melancholy. Well, most of them do. We haven’t checked in with Anna yet.

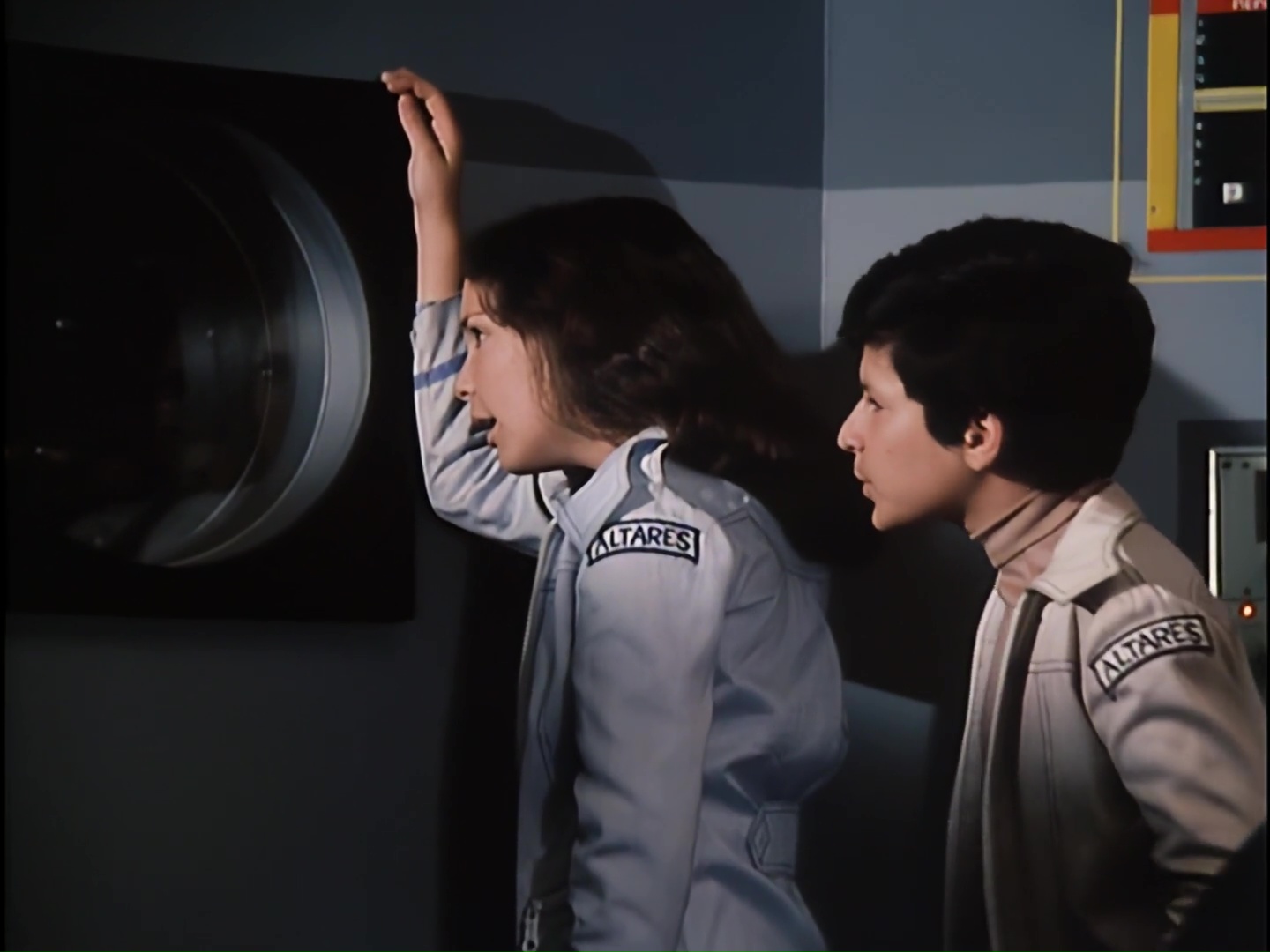

Some time later, the gang are still being menaced by that flashing red light. This time it’s there to warn them of some meteorites approaching. David has everything in hand and informs Captain Harry of the necessary course correction. He ain’t scared of a flashing red light.

Jane is in awe of the floating rocks. It must be said that floating rocks aren’t typically considered pretty. The special effects team try their best by shining a greeny-blue light at them.

Like a dull old man, David grumbles about the dangerous meteorite shower in order to crush Jane’s optimism. She takes the opportunity to nervously probe David on his intentions for the mission. He’s casual and flippant at first, just as we’ve seen him with the rest of his tasks so far.

Then, he pauses for thought and shares his desire to see what’s beyond Alpha Centauri in the depths of space and explore at least one of the Earth-type planets out there. He doesn’t make eye contact with Jane, just looks forward. He just contemplates the vastness of the universe despite the very human person standing next to him trying to make a connection. There’s so much potential for great depths to be explored with David’s character. Why is he so desperate to get away from Earth? Why is seeing the universe so important for him? Why is he so consumed by his work? The intention might have been on paper that young viewers are supposed to look to David as an ambitious role model – as a go-getting space explorer with no fear of the unknown. But Martin Lev’s performance is so haunting and mysterious, I personally see a young man with something of a difficult relationship with reality and an unquenchable thirst for something beyond what the normal human experience has to offer, at whatever the cost. Look, I’m not saying he’s evil, that would be silly, but I’m saying there’s great potential there for a darker side to the character, which could have had fascinating consequences if the series had continued.

Jane tries to gently test whether David has any fondness for his home on Earth, and whether he can really stomach 30 years away from home. She’s pretty crystal clear that she wants to get home sooner than that. Jane’s working hard to connect with David and keeps her emotions just under the surface in her eyes and her voice.

But after a brief glance at Jane, David’s back to being a quiet, solitary figure. He’s heard Jane’s intentions and realises they’re at odds with his own. Will he allow this human connection to interfere with his plans? We’ll soon find out. It’s an excellent little bit of drama that doesn’t push too hard. There’s just enough conflict there to dent the cheerful atmosphere of the mission, and that’s where the most intriguing stories often start.

There’s then quite a brief montage which gives an overall impression of a peaceful life aboard the Altares. It doesn’t actually show all that much. Jane has a snooze and then Tom shows us a screen with the words “Alpha Centauri” on it. I guess that means they’ve arrived at their destination. Presumably the passage of time is here to convey the vast distance between our solar system and Alpha Centauri. The music and shots of the various suns and such suggests we’re in an awe-inspiring part of space the like of which we’ve never seen before. Personally, I’m not necessarily over-awed by the change in scenery. That’s probably because I’m so used to seeing these sorts of establishing shots in Space: 1999 that I’m numb to the fact they actually mean something here.

Jane’s star-gazing again. She’s totally absorbed by the majesty of the universe. But is that a look of adoration or trepidation?

Harry can’t resist making a typical dad-joke at this point to lighten the mood. So lovely and charming and exactly what was needed to bring us back into the warm, family atmosphere.

Another short montage ensues, and the voice of Ed Bishop pops back in to explain exactly what the work is that the Altares crew now need to do in Alpha Centauri. The narrator suggests that they’re far too busy to ponder the magnificence of being the first people to see this part of space up close. They are there to research, not site-see and ponder. Yawn.

Look, I’m of the opinion that observations and art are critical to our understanding of the universe we live in. They put abstract concepts into frames of reference we can actually get our heads around and ultimately learn from – a bit like this very film. So the viewpoint that doing science is more important than watching and contemplating seems at odds with the purpose of The Day After Tomorrow. After all, Space: 1999‘s most successful episodes are the ones which ask the big questions and try to put visuals and stories to our philosophical and scientific musings about existence. Hardly anyone can tell you what Neil Armstrong read off his scientific aparatus when he set foot on the Moon, but we all remember the first words he used to poetically sum up his one small step. Sure, the science was important, but it was his words and expression of the moment that inspired future generations to do the same thing.

Anna’s back! Yes, she’s finally managed to get out of that chair and join in the fun. Goodness knows why she was kept out of every scene since the photon drive was activated, but it’s nice to have her back. It’s also nice to see Jane getting involved and enthusiastic about the work they’re doing after her initial nerves.

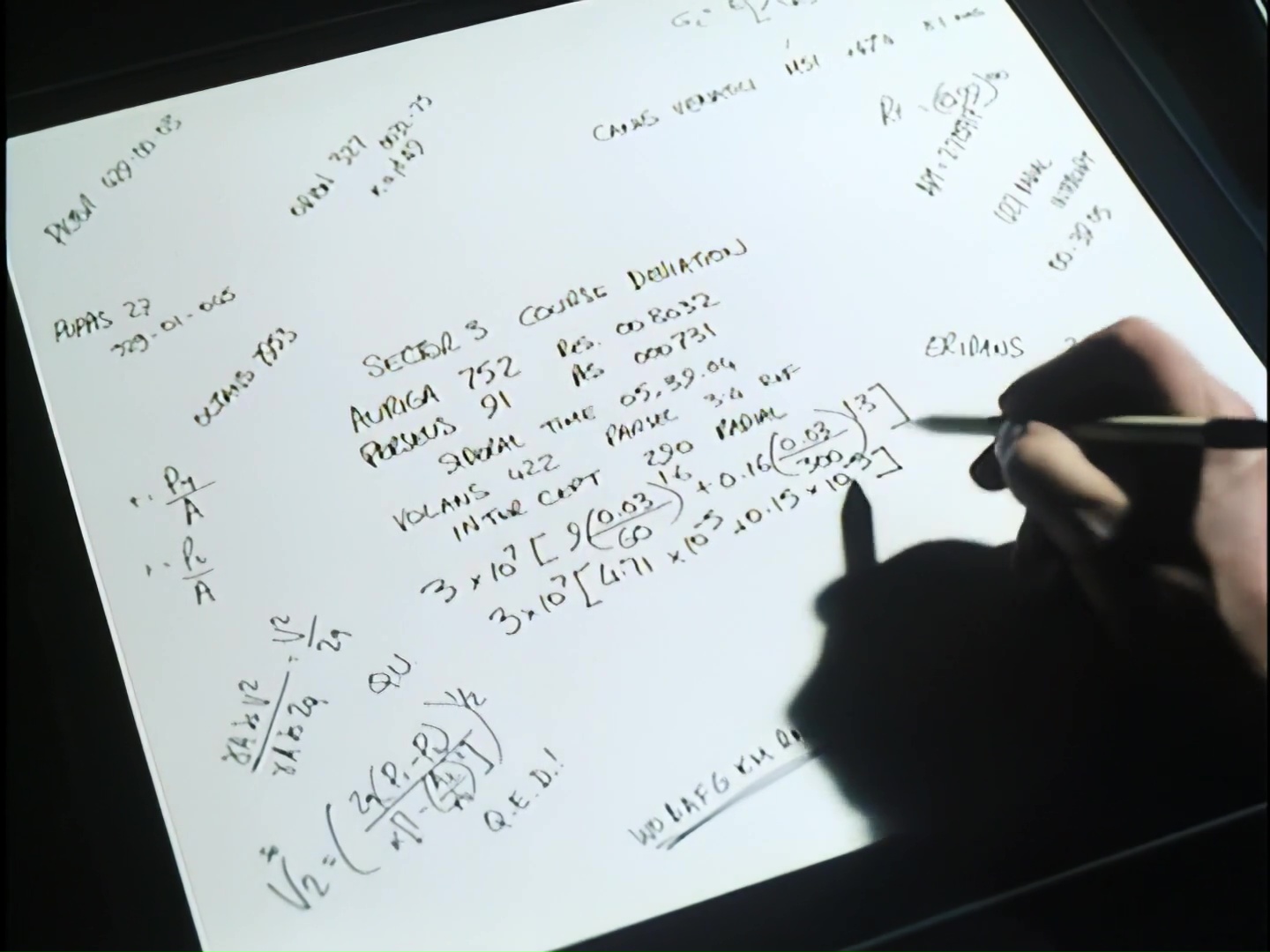

There is a man who knows how to flick a switch with a pencil in his mouth. The narrator explains that Earth’s future is in danger thanks to pollution and careless environmental destruction. He fails to actually elaborate on that point, but presumably the implication is that humanity will soon want to get out of town and find a new home out in space with the help of the Altares’ scientific data.

Anna looks at some dust while Tom does some maths to finish off the montage. I’m sure the numbers that Brian Blessed writes down are mostly nonsense, but if you look closely he appears to be charting the position of various celestial bodies in order to calculate their course deviation in sector 3. Clever stuff. The narrator explains that the crew will soon have to choose whether to journey forward into space or return to a version of Earth much older than it was when they left due to Einstein’s time dilation theory. Or… the third option would be to try tasting that delicious-looking space dust that Anna’s working on and let nature take its course.

Everyone takes a short moment to celebrate the completion of their work program. Unfortunately, this particular shot just makes it look like Nick Tate has something particularly menacing behind his back.

The families get into position to watch a transmission from Space Station Delta. Hopefully it’s not another repeat of Mrs Brown’s Boys.

It’s everyone’s favourite man who stands around outside your bathroom window, Jim Forbes! He makes an absolute hash of explaining clearly when the transmission was sent and when it was supposed to get to them and it’s all very confusing… well, it is for me. But basically the point is pretty simple – he now asks them choose whether to return to Earth, or travel forward to their next objective. Either way they’ll be heroes so no pressure or anything.

Jane’s feelings are clear. She’s not really a fan of sticking around in space with weird David.

Harry’s probably a bit torn. On the one hand, more flying a lovely big spaceship. On the other, working with Catherine Schell and Tony Anholt on more Space: 1999.

David’s already dreaming up names for the distant planet he’s going to colonise.

Anna is absolutely terrified by the possibility of spending any more time with her husband in this tin can. Tom thinks he might have left the gas on at home.

The message ends. That’s all we get from Jim’s special window for the rest of the film. He was another soothing, fatherly presence in the mix but never had much of an opportunity to make an impression.

It’s decision time and Harry takes command, of course. One descending voice and they return to Earth. I guess that’s a fair system. One space traveller who feels they’re being kept aboard against their will is one too many.

He pauses for just long enough to make him seem like a normal human, but David is the first to commit to moving forward into space. The determination in his eyes is frightening.

Anna and Tom agree with their son like a couple of parents trying to please a stroppy toddler. I’m exaggerating, of course, but the fact they keep their eyes locked on David does seem to suggest they’re making the journey for his benefit rather than their own.

Jane keeps quiet. Dare she face the wrath of David?

Look at him. Look at the fury in his eyes. He wants this more than anything and won’t let anyone get in the way. There’s a lot going on under the surface with this. Clearly, David is trying to silently manipulate Jane into taking his side. And just think about how much he’s asking her to give up to satisfy his own dream.

She quietly agrees, with what seems like a forced smile, to continue with the mission.

David grins like a devilish so-and-so who’s been allowed to have his cake and eat it. At least I think that’s how we’re supposed to interpret this smile. It could be genuine gratitude to Jane, or pride in her bravery, or any number of more positive things, but something about the music and the lighting and the editing of this scene really portrays David as the villain for me. His ambitions cause others to suffer in silence. Jane has just been forced to give up even more of the Earth she recognised as home, and it seems that David was the one who pushed her towards that decision. Who knows how this dynamic might have played out had the series continued? I really must read the sequel novel, Planetfall.

We’re spared from another face-wobbling sequence of intense g-force action and fade to a model shot of Altares flying away from Alpha Centauri.

The Altares enters and new star system and has to contend with the computer navigating through some gravitational turbulence. This translates to Joanna Dunham attempting to tumble from one of end of the tiny set to the other while the camera tilts the other way.

Jane is confused about the size of the suns they’re passing because despite being larger than our own sun, they actually look quite small. Guess what? Einstein’s got the answer, although Harry doesn’t exactly do much to explain any of it. He just says it’s because of their relative velocity. Guess I need ChatGPT to fill in the gaps…

Generated by ChatGPT 3.5, February 2024

Imagine you’re in a super-fast spaceship zooming past a really long train. If you could look out the window, Einstein thought that the train would appear shorter to you than it really is. It’s like the train got squished! This happens because, according to Einstein’s theory, as things move closer to the speed of light, they get shorter in the direction they’re moving. It’s not that the train actually changes size, but it just looks that way because of how fast you’re going past it.

Thanks, that’s a big help.

Jane is feeling particularly curious today so decides to asks Anna to info-dump some biographical details about Einstein pertaining to his later work on a unified field theory. I’d need a bottomless gin and tonic before I attempted to understand that one. Seriously, it’s another head in hands during a GCSE Physics exam scenario. As for this scene, well it’s probably one of the weakest in the film in my opinion. The Einstein lessons are very thinly veiled and some slightly juicier dialogue beyond Jane swooning over Einstein’s genius might have made this a more engaging moment. It is, however, intended to be the calm before the storm…

Mercifully, the flashing red light of doom is back to terrorise the crew. Charles Crichton really had a thing for that light, didn’t he?

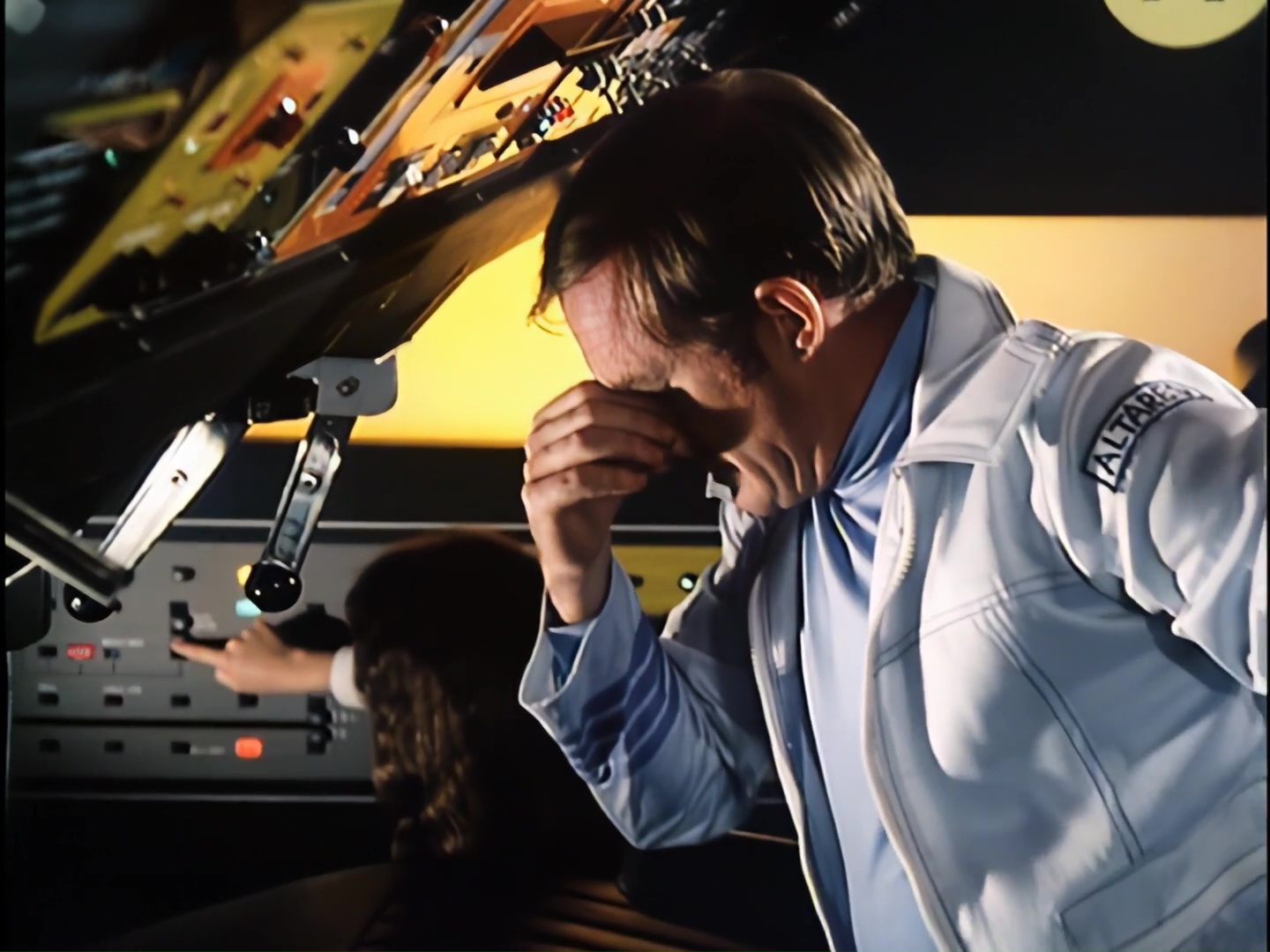

Tom leaps into action to activate the backup guidance system but it’s no use. Another meteorite shower is heading for them and this time David’s course corrections don’t come fast enough. Just to make things worse, the photon drive turns itself on while Harry and Jane wrestle with the ship’s controls. Much excitement! Wadsworth and Coe’s funky soundtrack really kicks in and does some magnificent stuff here.

Cor! It’s a little early for bonfire night isn’t it, Harry?! A few sparks on the set and suddenly the whole situation feels a lot more dangerous and chaotic.

As stars whizz by, Harry uses all his might to try and shut down the photon drive. Meanwhile, Tom and David run in and out to tell the captain that their navigation systems have all gone to pot and that it would probably be a neat idea to switch off the photon drive. Thanks guys, you’re really a terrific support.

Don’t worry, Jane knows where the big failsafe button is and they soon start to slow down. She’s very pleased with herself and looks to Anna for approval. It is nice that the two of them share a bond, especially since Jane’s mother is absent for reasons left unexplained. That said, I don’t necessarily think Anna just being a mother to everyone on the ship is a particularly interesting character trait and she probably needed a bit more to work with.

The gang really do look jolly as the suns fly on past as if all their problems have miracously been solved.

No such luck. The failsafe… sort of… fails. The photon drive cannot be stopped. Harry is defeated. It’s brown trousers time.

While space goes bananas outside, the gang are understandably a bit miffed. Einstein’s theory states that nothing can travel faster than light and yet the Altares shows no signs of slowing down. David’s tiny mind can’t comprehend it. Again, it’s up for some interpretation, but I can’t help but wonder whether David feels slightly responsible for their current predicament. After all, he’s the navigator and seemed to miss the meteorite shower. And if he hadn’t passive aggressively bullied Jane, they’d be flying in the other direction towards home right now. That’s just one way of reading it, of course, but it does make for a neat character arc.

Suddenly, Captain Harry considers himself above Einstein and couldn’t give half a toss about any theory of relativity. It’s time to strap in and travel faster than light. Oh boy, oh boy. Let’s mess with some science. Brian Blessed, Joanna Dunham, and Martin Lev do the best acceleration-acting they can considering the set is totally flat and there’s not so much as a light breeze standing in their way. Bright lights flash past the ship pretty bonkers-fast now.

Anna has to go and take her seat in the back so she’s got the hardest job getting around. Tom could have been a gent and offered up his much more accessible seat to his wife, but I guess chivalry is dead in The Day After Tomorrow.

Charles Crichton seems to like close-ups of Anna’s hands and the wedding ring the character wears. Maybe it’s a coincidence or maybe it’s some kind of deep statement about her role as a wife being at odds with her role as a space explorer… because it was the 1970s and a bloke taking his missus out anywhere was probably still viewed as the height of inconvenience. I could be reading too much into things though. I have been known to do that.

Acceleration getting spicy now.

My goodness she tries to make it look convincing, but no amount of backcombing Joanna Dunham’s hair can sell the idea that the intense g-forces have thrown her against the back of the otherwise motionless set. It’s a dramatic moment, sure, but maybe a wee bit comical if looked at too closely.

While David pulls a face like a child being force-fed broccoli, Tom is now taking an interest in his wife’s safety and plans to come and rescue her. If anyone can fight the speed of light itself, it’s Brian Blessed.

I’m starting to think Charles Crichton didn’t like Joanna Dunham very much.

Yes, Tom! Do it! Punch the little twerp in the face! Oh… no… sorry, yes, struggle against the acceleration. Yes… do that.

So yeah, this space travel thing might not be all it’s cracked up to be.

As they continue to barrel towards the speed of light, the Altares streaks through veritable clouds of starfields which blast around the ship. The visuals are really stunning and it’s a great cliffhanger to end the second act on.

When we fade back in, the Altares is parked next to a friendly-looking pink blob in space. All is calm and serene.

They’re pretty exhausted from their high-speed thrill ride, but the crew slowly start to wake up to discover that the failsafe system has finally managed to pull its finger out and actually stop the photon drive. Some engineers are going to get a stern talking to if they get back to Earth. But hang on a moment – Harry’s okay, Jane’s okay, Tom’s okay, David’s okay… are we forgetting anyone?

Oh yeah, once she’s been scraped off the floor it turns out Anna’s okay too. Her first concern is whether the children are okay. That’s right, both of them. How nice. She really is just characterised as everyone’s mum at this point. Heck, maybe she is Jane’s mum… maybe that’s a whole soap opera plot point we would have gotten later in the series.

On the whole, I love Derek Wadsworth and Steve Coe’s score for The Day After Tomorrow, but if there’s one thing I could throw off a bridge tied to a block of concrete, it’d be that twee bit of organ music that accompanies all the lovey-dovey moments in the film like this hug. It’s a bit naff and it cheapens the moment and the actors’ performances. But hey, at least David’s finally showing signs of responding to genuine human connections. He might be an aspiring cutthroat space explorer, but when it comes down to it he loves a hug from his mummy. Again, that deleted scene of Anna and David doing a medical check-up might be the reason this emotional reunion is emphasised so heavily. Perhaps the intention was for David to have some pre-exisiting condition we don’t know about in the finished film.

Time for an assessment of the situation and Captain Harry isn’t feeling too positive about any of it. No drive power. No sense of flight-time or distance travelled. But they do have oxygen which will be jolly useful if the film is to have any chance of continuing.

The two dads share a moment of seriously intense looks as they conclude they’re billions of miles off course – a whole solar system’s worth of distance. They’re lost with no recognisable landmarks nearby. The men silently consider what this could mean. One of them might have to eat the other… well, that could be an interpretation anyway.

Anna immediately looks to Jane to see how she’s taking the news of their predicament. Not the cannibalism thing, I just made that up, but the being stranded in space for the rest of their lives thing.

David, always the most determined of the group, suggests that they try to lock on to Space Beacon Delta to figure out their position. Presumably he’s referring to the same Space Station Delta that we were introduced to at the beginning of the film, positioned in Earth’s orbit. That sounds like quite a long way away from wherever the heck they are now.

“Like looking for a needle in a billion haystacks,” is Tom’s cheery way of describing the challenge. A billion haystacks. That’s a lot of haystacks. I can maybe imagine twenty or thirty haystacks. I reckon I could probably find a needle in twenty or thirty haystacks with enough time and the right equipment… a metal detector would probably be quite handy in that scenario. So for a billion haystacks I’d just need a few more metal detectors. I’m sure once I had the process down I could pick up the pace and the search would be over pretty quick. And who knows? You might get lucky and find the needle within the first hundred thousand or so haystacks that you search. Then you could take the rest of the year off… sorry, where were we? Oh yeah, Einstein and stuff.

Next problem, how do they fix the photon drive? Anna’s apparently the person to ask about the heat and radiation situation inside the drive chamber. I guess because she sits closest to it she’s the expert.

Considering the relative simplicity of the set – a long tube with camera access on the port side – Charles Crichton manages to find a satisfying range of dynamic shots to get us through the film. The translucent coloured panels in front of the drive chamber just break up the set enough and by shooting through them we’re offered some alternative tones on-screen that keep things interesting. Staring at a completely grey set with nothing else to offer for 47 minutes would be a bit of a struggle.

Two bits of bad news unfortunately. The heat insulation has given up the ghost, and they don’t have time to wait for the chamber to cool down by itself because the ship is drifting towards a sun…

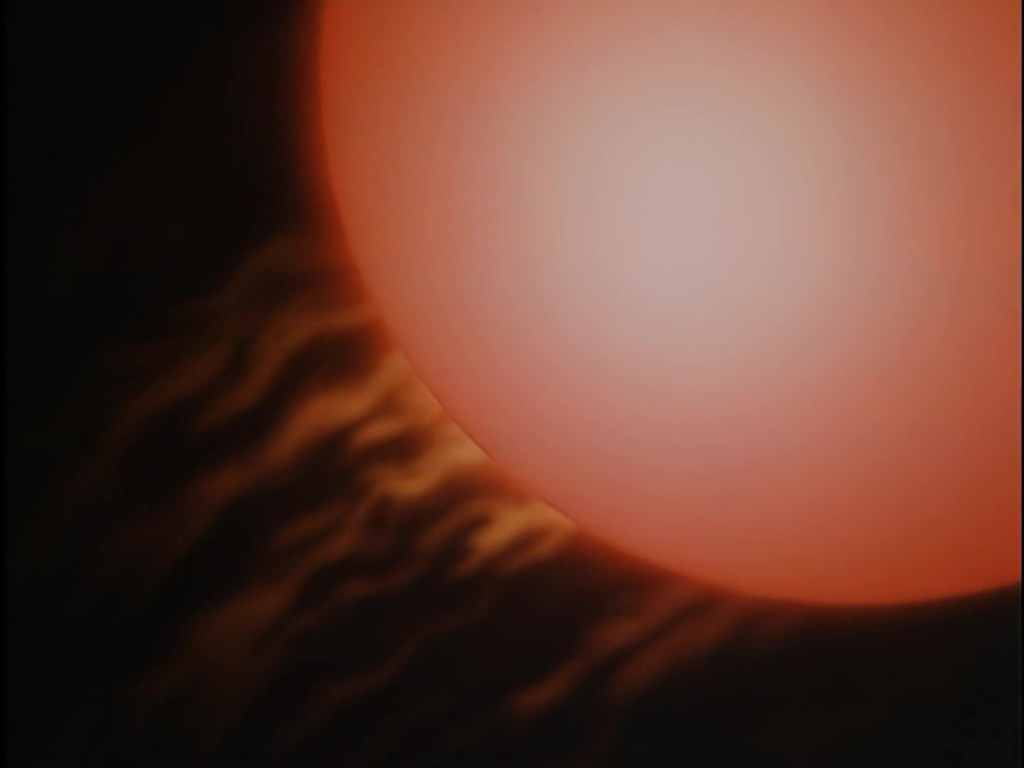

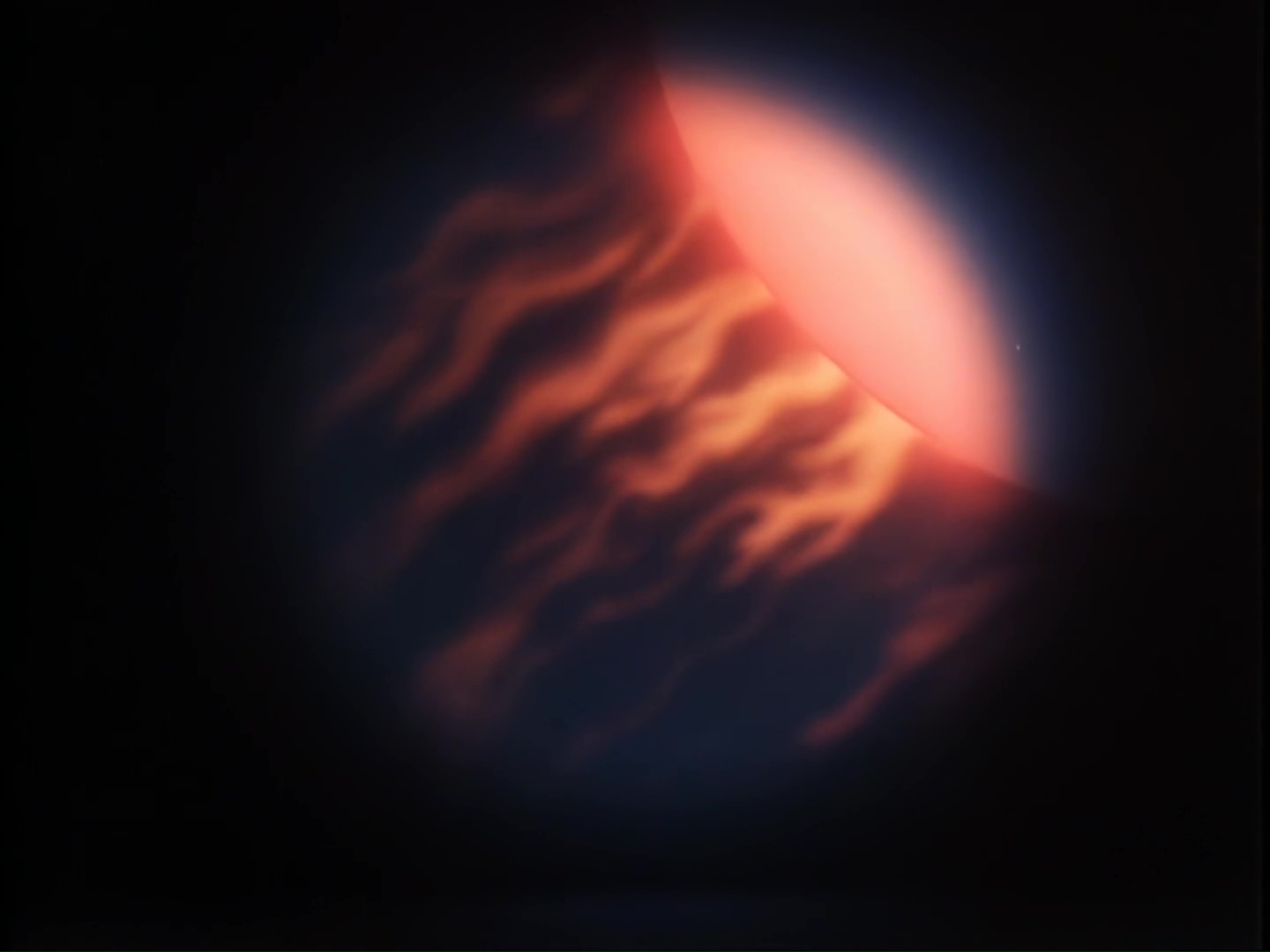

Turns out the friendly pink space blob outside isn’t so friendly after all. Well, it does want to make friends with the Altares but only in a melt-your-face-off sort of way.

With no time to waste, Harry plans to make the necessary repairs to the drive despite the immense heat. He’s such a gosh darn hero. Jane hovers over her father’s shoulder in the background, just so we know very clearly what Harry has at stake.

Knowing full well that Harry is a rule-breaking fool, Anna is quick to remind him again that after 15 minutes inside that chamber he’ll be toast and he must not go beyond that limit. I’m not entirely sure how Anna calculates the 15-minute limit exactly, but she’s the ship’s doctor or something so I guess we have to trust her. Of course, they don’t put an exact figure on how hot the chamber is so that leaves Johnny Byrne’s script a heck of a lot of leeway.

Just so everyone at home can have a handy visual reference for how much time Harry has in the chamber, Anna sets up a timer on the wall… not actually sure what the timer would be used for in normal circumstances but it’s certainly useful right now.

Jane and her father share a sweet moment together so that the audience has some emotional weight to connect to in amongst all the more unusual dangers the crew are facing right now. Jane doesn’t want her dad to take unnecessary risks because he’s all she has left at this point. Even though he’ll only be gone 15 minutes, he offers her a parting kiss on the forehead because I think Harry knows he has to fix that drive in order for Jane to survive, whether he makes it out of there in one piece or not. Her survival is more important than his own, even if she desperately wants him not to risk his own life. These stakes and this drama is far more meaningful to the audience than their rate of drift towards the sun, or how many billion haystacks need to be searched for a needle.

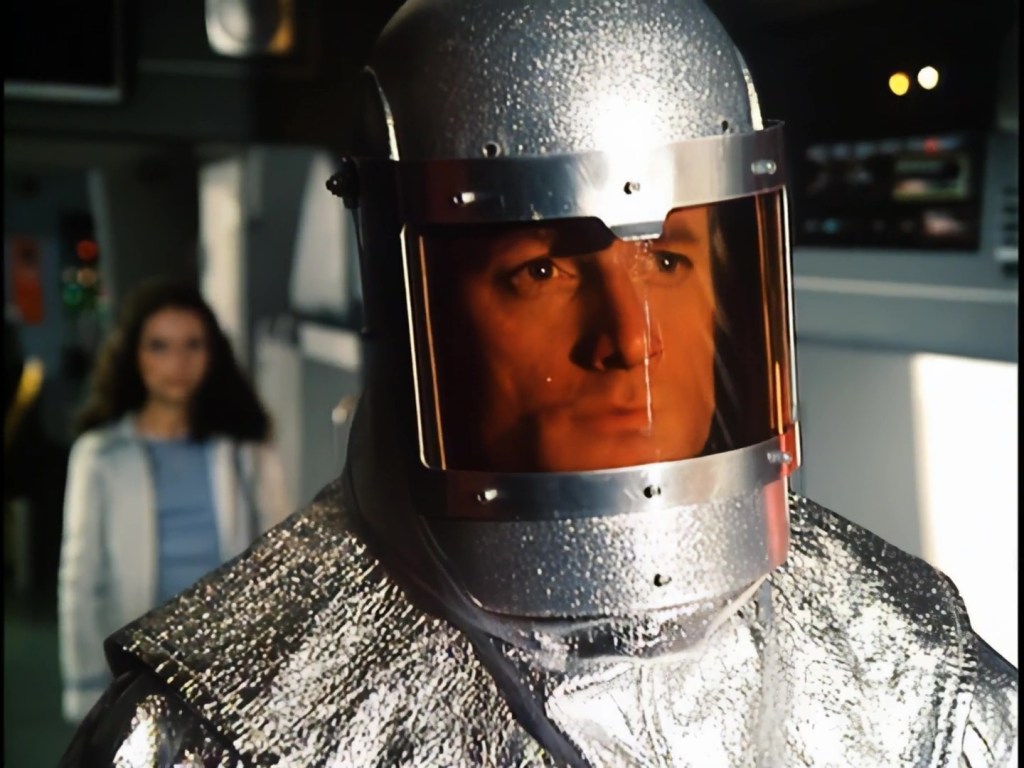

Nick Tate works dang hard to make that shiny boiler suit look heroic. The expression of fear mixed with determination on his face is perfect. Gerry Anderson was so right to put Nick Tate in the lead role for this film because he just is a space hero.

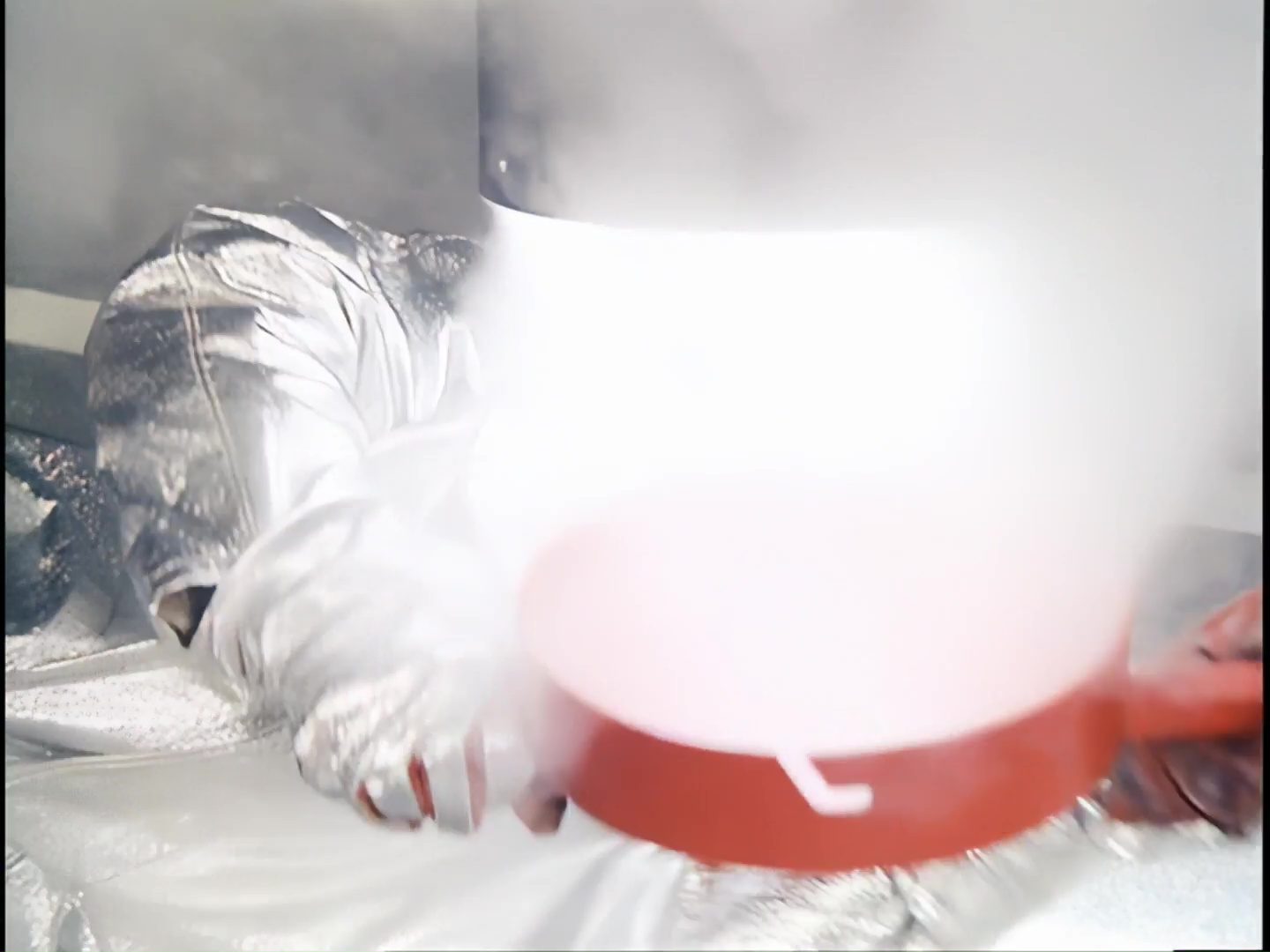

It’s another trip into the unknown for this little family, even more dangerous than the one we’ve witnessed so far.

While the rest of the Altares set borrows from Keith Wilson’s sets for Space: 1999‘s first season, I think the drive chamber is a totally new set by Reg Hill and it’s very 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s a brightly lit, completely round tube designed to feel hostile and inaccessible for the crew, compared to the more neutral main cabin set. Dare I say it though, the set is also rather lacking in detail. Sheer white walls, a few colourful pipes, and control panels only where they are strictly necessary doesn’t exactly suggest a complex photon drive system to me. I’m not saying Reg Hill wasn’t up to the job of designing the sets, but the extremely tight budget doesn’t seem to have done him any favours with this one.

The handy timer is reset to 00 as Harry awkwardly shuffles along the narrow passage between the drive unit and the wall. It really is a tiny and cramped set and I’m not sure how much of that was deliberate. You just know that if this same room was being delivered on a Space: 1999 Year One budget, it would be a massive space full of control panels and flashing lights and big, chunky, serious-looking components.

Meanwhile, David tries to do a thing with a thing but then shakes his head to mean he thought he’d managed to do the thing with the thing but had in fact not quite managed to do the thing with the thing… probably some sciencey stuff to find the Delta Beacon… I don’t know, I spent my GCSE Physics exam with my head in my hands.

Purely for the benefit of the camera, the drive units are clearly labeled as dangerous. Jane watches anxiously as a minute passes on the clock. Again, she’s the audience surrogate so if she’s watching anxiously, you should be watching anxiously too.

Nick Tate once again does some of his best work trying to make Reg Hill’s bright red dustbin lid look heavy and important. Seriously, I’m not buying that this is a drive unit capable of propelling a futuristic ship into space at the speed of light. The set needed way more detail, and surely in spite of the low budget a more visually interesting system could have been devised for Harry to access the drive unit. I’ll give them this though, the angry plume of white light and steam that roars in Harry’s face is very effective. The sound effects and the tense music are also doing a lot of heavy lifting for this sequence.

A fade transition and the handy clock on the wall indicate a passage of time. The Bowen family (aka the science nerds), are occupying themselves with a study of the sun that’s currently trying to make friends with them. According to Tom their rate of drift is increasing but nothing to worry about yet. Anna on the other hand has a slightly less positive outlook…

Jane mournfully appears over Anna’s shoulder, just in case you’d forgotten that her father is still risking his life during all this. But we’re now receiving a really good, subtle education on what happens to a star towards the end of its life. I couldn’t say whether the figures about size, mass, and density that Anna reads off are accurate to produce a supernova, but it gets the general point across.

The science might be a mystery to some of us, but the lighting and direction and performances speak for themselves. Things are seriously not good.

Harry is making progress on the repairs but he’s clearly struggling and there’s no end in sight. Brian Blessed plays the situation so delicately. You can see in his face that Tom is thinking through their options and trying to balance out every factor to solve the predicament. It’s a calming, fatherly presence but its undercut with tension and the weight of responsibility the character feels.

While David, Tom, and Anna all have jobs to do assessing the red sun, Jane is left alone to process the information. The shot of her slowly approaching the window and being consumed by the deep red light is incredibly powerful. It’s like Jane is looking into the eye of an enormous, terrifying monster. As far as she’s concerned that’s what it might as well be. To her, and many of us at home, the only thing that matters is that it might kill them all. The various stats and atoms that make it up might not mean much to us but we understand that it’s a danger unlike anything we’ve encountered before simply because of the way Jane looks at it. She’s not in awe of the universe any longer – right now she’s terrified of it.

The same, menacing red glow engulfs the Altares model as it appears to shrink away compared to the not so friendly pink space blob.

Jane and Anna share a brief moment to put a name to the terror they’re facing – a red giant. But the reason Anna and the others aren’t running around screaming is that they don’t have any idea how stable it actually is. She attempts to reassure Jane that they could be completely safe from the risk of it blowing up for absolutely ages. The chat seems to do just enough for Jane to hold it together.

Her emotions are starting to bubble up just under the surface as her father’s timer gets close to the limit. The incidental music has started to take on a more funereal tone…

Again, Nick Tate is acting his socks off to make it look like he’s struggling against the heat and the stubbornness of the drive unit, when really he’s waggling a few props around in some white steam.

The flashing red light of doom is back again with all of its glad tidings.

Basically, the Altares crew have gotten very, very, very unlucky and arrived on supernova day. Being able to spot that through a glorified telescope is jolly convenient.

As one might have anticipated, Jane isn’t thrilled with the idea of telling her father about their impending doom because he’ll end up risking his life to fix the photon drive.

Jane is quickly outvoted – another instance where control over her own life is superseded by the Bowen family – and Harry takes the news about the supernova with a trademark coolness. Jane on the other hand, is beginning to lose it as she realises nobody is going to listen to her.

Time ticks along and Harry is beginning to get tired.

The situation’s looking pretty hopeless for them all. There’s no more research or statistics for the Bowen family to find out. It’s no longer about the science but about the passage of time and their survival. And Jane has more at risk than most.

And just when we think for a moment that the job is done as Harry seals the top hatch, he then slides down and gets to work on the bottom hatch as well. A hatch that looks even more awkward to work with than the first. This is really starting to take the biscuit.

David finds himself caught between two different infernos. The red giant raging outside, and Jane on the brink of an emotional breakdown. There’s a sense that he understands the burning star far more than the fragile teenager desperately waiting to see her father return.

As Harry wrestles with the drive unit once more, Jane begins to get twitchy. She notices David keeping his eyes fixed on the sun outside. Why should she choose the crew’s safety over her own father’s, when it was David’s determination that robbed her of an opportunity to get them away from all this? And even now, David’s choosing not to engage with Jane’s struggle or offer her any reassurance at all. Why should she surpress her feelings for his benefit?

And so, as the Altares slips closer towards its doom…

Jane decides that is enough is enough. No more sacrifices. She runs for the radio and pleads for her dad to come out of the deadly heat. No matter the odds, she will not give up her father for another second.

Harry does all he can to reassure his daughter.

Anna steps in to calm her down too, reminding Jane of what they all signed up for during training, including her father. There’s still a chance and nothing bad has happened yet. David looks on in the background, keeping his distance, relatively unstirred by the outburst.

Is that a twinge of guilt on his face? Or fear? Or affection? Or anything? Outburst over, David turns back to the red giant, no longer prepared to engage with these feelings.

The soundtrack is dominated by the deep rumbling of the raging sun.

Harry’s time is up and Jane can’t handle him being in direct danger.

Tom is in agreement and urges Harry to give up and let him take over. But the captain has other ideas, and stubbornly refuses to leave until the job is finished no matter how uncomfortable he may be.

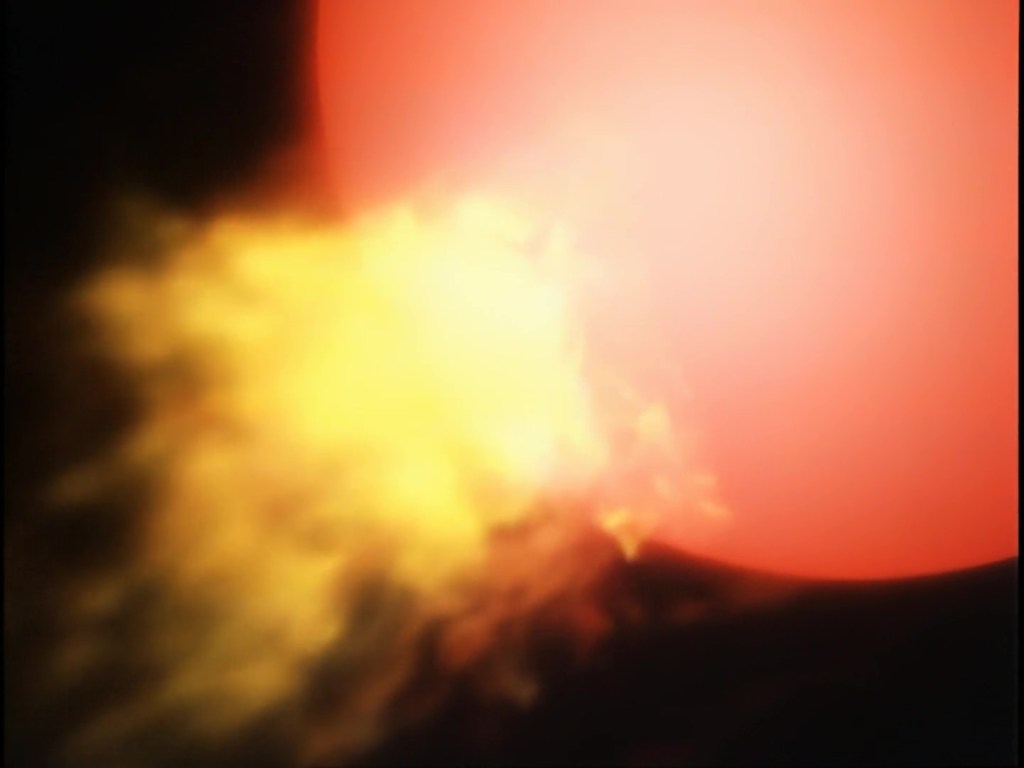

The sun is out of time too. It spits out a beautiful cloud of flame. The Space: 1999 effects crew at Bray Studios really were very well trained by this point on how to do weird lighting and space phenomena.

David actually looks worried for the first time. Harry’s breaking the rules. Tom’s taking matters into his own hands. Jane is distraught. Anna has no support left to give. Everything is getting turned on its head in this moment of distress.

But as Harry stumbles back towards the door, there’s a quiet chance that all is not lost.

Absolutely gorgeous, psychedelic waves of flame billow from the sun. Obviously, nobody’s had a good look at a sun blowing up before, so I love that the effects are so creative and manage to make it look simultaneously threatening and beautiful.

I don’t know exactly what’s active now, but I assume it’s good.

Brian Blessed gives a frantic, very physical performance as he wrestles with Jane to keep her safe from the burning heat of Harry’s suit, and then carefully grapples with the Captain to get him sat down. Tom is fully in command at this moment and orders Jane to do her duty and pilot the ship.

Anna injects Harry with something, presumably to help with the intense dehydration or burns or the myriad of other health issues he now has after working in that chamber. Tom firmly demands that Jane get the Altares moving with Anna’s help. Confident enough that her dad is okay, she rushes to take his seat at the helm. The music matches perfectly with the fast-paced action. It’s a terrific sequence.

Just as the Altares is consumed in the flames, Tom and David take their seats and Jane activates the photon drive at full blast. The incredible pace of the editing easily covers any awkward “acceleration” acting that the cast have to do to try and sell this moment.

It’s an absolute assault of crash, bang, wallop in the finest Gerry Anderson style. Music pumping, explosions blazing, lights and visuals flashing all over the place. You feel the full force of the supernova and the race of the Altares to escape it. Amazing action, expertly realised in all departments.

The fourth act opens with the Altares safely clear of that not-so-friendly pink blob in space that tried to eat them with fire. Aside from a few bits and pieces scattered across the floor, all appears to be well as Harry recovers from his ordeal. Jane couldn’t look happier with it all.

Anna checks in on Harry in her capacity as the ship’s doctor, but also with something of a wifely tone. I don’t know, I think there might be something to the theory that these two had a thing at some point…

Naff hugging music aside, this is a sweet moment. After all the worry that Jane went through, and the danger Harry put himself in, it’s really nice to get back that warm, family atmosphere. Jane still has the one person she needs in the universe, and so does Harry.

The reunion is brief, as the crew gather to inspect a signal that David and Tom have picked up. Yes, the plot has to keep on moving!

After a little bit of computer business to build tension, it’s revealed that the signal is indeed from Delta. Tom and Harry share a manly embrace of joy. Seriously, between the two of them Brian Blessed and Nick Tate have more testosterone than a field of randy bulls.

With a little more computer business, Tom works out that the signal was transmitted fifteen years since the Altares set off. Einstein and time dilation and bla, bla, bla – you know the drill. Jane shares in the two dads super-duper-hyped enthusiasm for turning the ship around and heading for home. But Anna doesn’t look quite so thrilled. Yes, it’s finally time for us to get a deeper insight into Anna’s character…

The Bowens share an emotionally complex moment by the window. Anna is struggling with the prospect of going back to Earth and suddenly seeing their parents fifteen years older or deader than they were when the Altares left. Tom insists that they’re going home, but Anna is clearly not convinced. It’s pretty clear that without the family she knows and recognises there, Earth won’t necessarily feel like home for Anna any more. The scene is tenderly performed by Joanna Dunham and Brian Blessed, and really contributes to the emotional dimension of the film. It isn’t just young Jane who is vulnerable and scared. The adults are stumbling with their feelings too. Sure, it’s a little bit of a stereotype for the two women to be the ones worried about family and the emotional weight of the adventure, while the lads are busy doing science and being terribly practical about the whole thing, but at least it’s being discussed in some form. Maybe if the series had gone on, we would have seen Tom, Harry, and even David become more sensitive and emotionally intelligent.

The Altares trundles along quite happily. Despite some of its technical failures, the ship has done a decent enough job at keeping the crew alive so far.

But it isn’t smooth sailing for long. The ship starts to encounter some navigation trouble due to an unknown source of immense gravitational pull. I have a similar issue after having too many gins.

Correcting the course doesn’t have any effect, no matter how much power Harry pumps into the photon drive. Tom’s on the case. He goes to his trusty card printing thingy on the wall which tells him what to do next.

Anna activates a laser and Tom isn’t too impressed when the beam goes all wibbly. In fact the music begins to suggest that they’re in just as much trouble as they were with the supernova. These guys just can’t catch a break can they?

In a haunted tone, Tom gives Anna the bad news. It’s a black hole. She immediately appreciates the gravity of the situation… get it?

Harry’s reaction to the news? Let’s outrun the darn thing. Yup, if anyone can take on a black hole it’s our heroic Captain Harry Masters.

Well, the thing about a black hole – it’s main distinguishing feature – is it’s black. And the thing about space, the color of space, your basic space color – is it’s black. So how are you supposed to see them?

Holly, Red Dwarf, Series 3 Episode 2: Marooned

Harry tries to get the photon drive to cooperate and hold their position away from the black hole while Anna runs an analysis and Tom transmits the location to Delta Beacon – either to warn future space travelers to watch out for it, or in case any poor souls want to come looking for the annihalated remains of the Altares… if you’re feeling pessimistic.

It’s an opportunity for David and Tom to chat a bit about black holes, but they don’t have an awful lot to teach us because, well, nobody’s gotten close enough to have black hole to have a good look. Basically, black holes crush and swallow all matter and poop out stars. That’s about the jist of it.

Anna’s report suggests that the black hole might be rotating. Rotating black holes initially sounded like a made up thing to me, but apparently it’s got some real science behind it. I’ll let ChatGPT have a go at explaining: